Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

This may be the world’s oldest surviving evidence of supersize thirst quenchers. Mysterious scepters found in an ancient burial mound could actually be giant drinking straws – and they were used to consume mass quantities of beer.

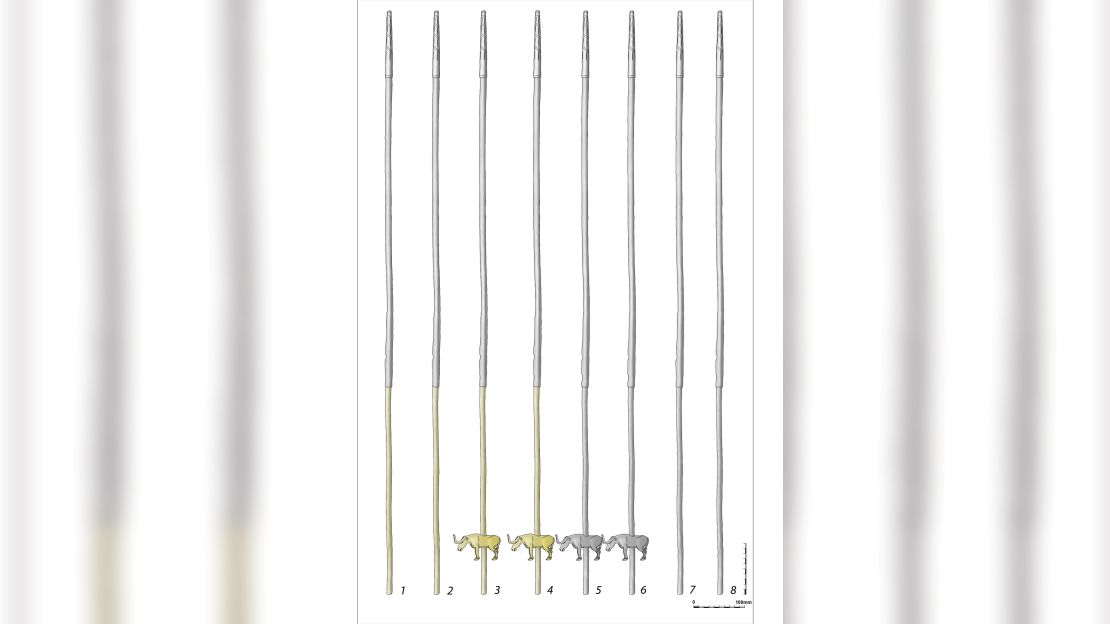

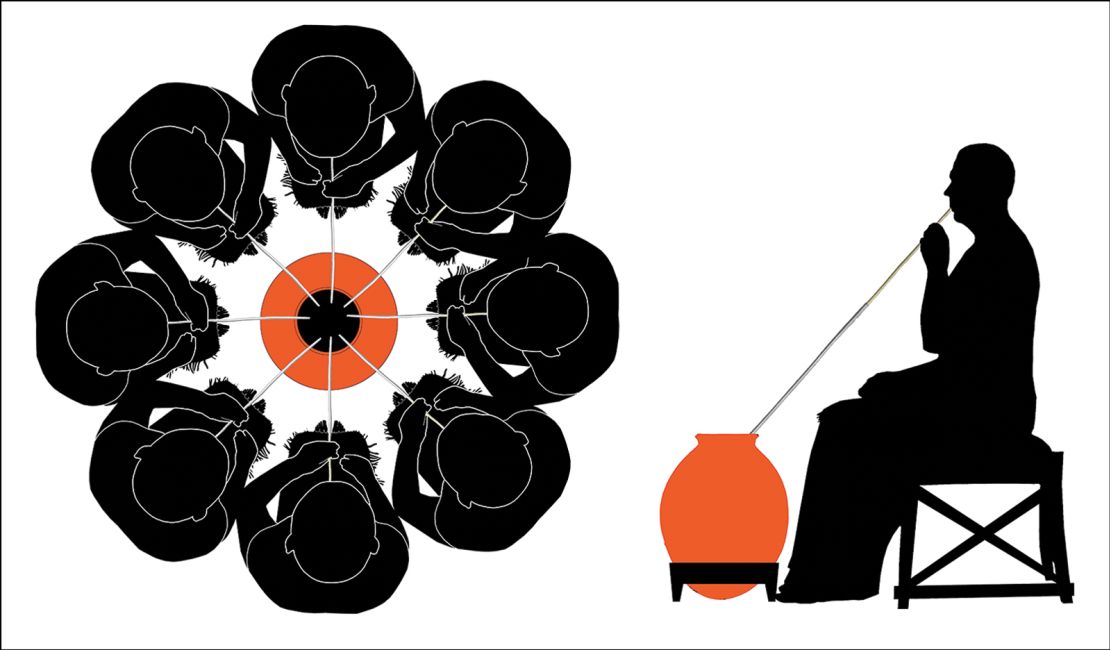

The gold and silver straws, each measuring about 3.6 feet (1.1 meters) long, are over 5,000 years old. While these straws sound comically long, with Dr. Seuss-like proportions, researchers believe they were used to drink beer from communal vessels during banquets to honor the dead.

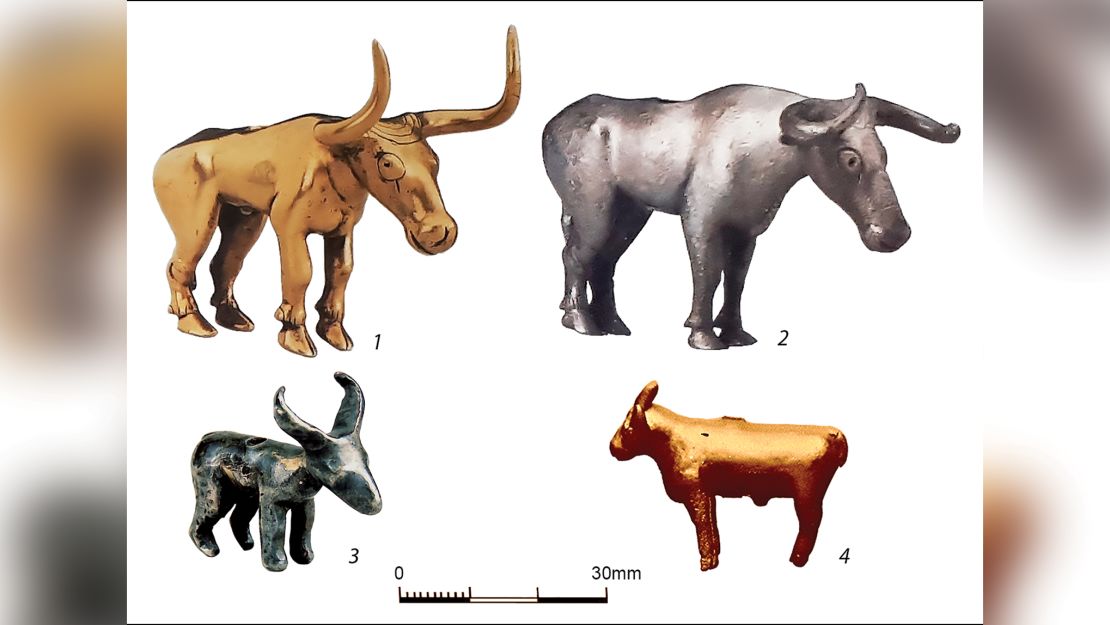

The fancy straws, four of which were decorated with bull figurines, include punctured metal pieces to filter out impurities in the beer, like sediment or husks.

The straws, along with one of the beer vessels, were found at the Maikop kurgan, a prehistoric burial mound in the northern Caucasus in Russia. The vessel was so large that it would have enabled each of the eight drinkers to down seven pints apiece.

A grand discovery

The mound was first excavated by archaeologist Nikolai Veselovsky, a professor at St. Petersburg University, in the summer of 1897. Within the mound, Veselovsky found graves belonging to elite members of Bronze Age society, including the remains of three people and hundreds of special objects.

Within the largest burial chamber were the remains of one individual wearing what was once a “richly decorated garment.” Hundreds of beads, semiprecious stones, gold, ceramic vessels, metal cups made from precious metals, weapons, and tools were included in the grave.

And then, there was a set of eight gold and silver tubes at the right hand of the skeleton. Veselovsky assumed they were decorative scepters and that the perforations at the tip of each one was once used to attach ornaments or horsehair.

In the fall of 1898, Veselovsky moved all of the material from the mound to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, presenting the collection to Tsar Nicholas II and the Romanov family during a special exhibition.

Over the last century, other researchers have debated the real purpose of the “scepters.” One suggested that the tubes were part of the structure for a folding canopy used during the funeral procession for the person in the burial chamber. Another thought they may be symbolic rods used to represent arrow shafts, given that arrowheads were recovered from the mound.

Communal drinking

Viktor Trifonov, an archaeologist from the Russian Academy of Science’s Institute for the History of Material Culture, and his colleagues poked holes in all of the previous theories, namely because those objects likely would have required solid metal pieces rather than hollow tubes. The number of tubes and their position at the right hand of the skeleton also suggested they were something else.

“A turning point was the discovery of the barley starch granules in the residue from the inner surface of one of the straws. This provided direct material evidence of the tubes from the Maikop kurgan being used for drinking,” said Trifonov, lead study author, in a statement.

Trifonov and his fellow researchers published their findings Tuesday in the journal Antiquity. While they cannot confirm that the barley residue in the straw had been fermented, there is other previous evidence to suggest that the researchers are on the right track: art.

The oldest evidence of straws being used is actually depicted in art from Iran and Iraq that have been dated to the fifth and fourth millenniums BC, showing people using straws to drink from a communal vessel.

Using long straws to drink beer together was also common for the Sumerians, an early Mesopotamian civilization from the third millennium BC, according to their artwork.

The Maikop straws looked remarkably similar when compared with the Sumerian depictions of straws, including metal strainers.

“If the interpretation is correct, these fancy devices would be the earliest surviving drinking straws to date,” Trifonov said.

A desire for luxury

The Maikop straws came from a site that is hundreds of miles away from where straws were used in Mesopotamia, suggesting that the use of straws must have spread between regions.

“The finds contribute to a better understanding of the ritual banquets’ early beginnings and drinking culture in hierarchical societies,” Trifonov said.

Perhaps those at Maikop were connected with other societies to the south – and wanted to enjoy a similar style of luxury and include drinking ceremonies. In Sumeria, communal drinking was part of a banquet that accompanied royal funerals. Given the placement of the straws in the Maikop burial mound close to a person of importance, it’s likely that this group observed the same practices.

While these decorated tubes may sound like the precursor to reusable metal straws that the environmentally conscious use today, it’s unknown if they were reused before being buried.

“Before having done this study, I would never have believed that in the most famous elite burial of the Early Bronze Age Caucasus, the main item would be neither weapons nor jewelery, but a set of precious beer-drinking straws,” Trifonov said.