Will Pucovski should have spent the last few months opening for Australia in the Ashes. Instead, the 23-year old batting prodigy has been recovering from what is believed to be his 10th concussion. He experienced the first while playing Aussie rules as a teenager, a teammate’s knee crashing into his skull during training and forcing him to take six months out of school. Since then, the hits have kept coming at an alarming rate: he’s bumped his head on a door at home, on the turf when diving to complete a run, been hit by an errant ball at training, and received several blows to the head while batting. All of these have led to concussion symptoms and spells on the sidelines.

His latest concussion, sustained in October when Pucovski was struck in the nets, ended his hopes of featuring in the Ashes. It’s a troubling situation for a rare talent who made an accomplished half-century on his Test debut against India last January, before improbably (or perhaps inevitably given his bad luck) dislocating his right shoulder while diving for a ball in the field. He has not played a professional match since.

Closer to home, Harvey Hosein, Derbyshire’s 25-year-old keeper-batter, was forced to retire in October after missing much of last season with concussion. He suffered four concussions playing for the club, two of those last summer, and with the symptoms of each more pronounced than the last, he felt he needed to protect his long-term health by calling time on his promising career.

“I don’t know if I’m particularly susceptible to this sort of thing, but the recovery time and the symptoms just took longer to get over and got worse and worse each time,” Hosein told the Times. “And the medical staff had increasing concerns about the long-term effects on my health, especially if there was to be another blow to the head, you know at this stage it could be disastrous.” He went on to describe headaches, fatigue, sensitivity to light and extended periods of “being very spaced out and not feeling quite fully there”. “It was really quite scary,” he said.

The cases of Pucovski and Hosein are at the extreme end of the scale, but they are not freak occurrences. There is mounting evidence that cricket, like many other sports, has underestimated the frequency of concussions. A landmark 2018 study of more than 300 Australian professional cricketers, conducted by Thomas Hill, John Orchard and Alex Kountouris (the head of sports science and sports medicine at Cricket Australia), found that head impact occurred every 2,000 balls and concussion every 9,000 balls in men’s domestic cricket. That roughly equates to a concussion one in every four first-class fixtures.

In women’s cricket, head impacts were considerably rarer, but 53% were diagnosed as concussions, compared with 32% in men. “Concussion in cricket is not as infrequent as previously assumed,” concluded the study. “Ongoing review of the rules and regulations is required to ensure that protection of player welfare lies in parallel with other sporting codes.”

In August 2019, the ICC introduced concussion substitutes, Marnus Labuschagne becoming the first in Test cricket later that month when he stepped in for Steve Smith at Lord’s. And further change could be on the horizon, with the game’s administrators mindful of both player welfare and the costly lawsuits related to brain injuries that are being witnessed in American football, rugby and football.

Last May, Nigel Huddleston, an MP who works at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, said that “huge litigation” could “undermine the financial viability of sports”. He went on say that the threat could be mitigated by “changing the nature of the guidance of how those sports are conducted”. In other words: adapt or face the consequences. And action is being taken across a range of sports.

In football, the game’s leading bodies have agreed new guidance limiting players to 10 “higher-force” headers a week in training; in rugby union, there has been a crackdown on high and dangerous tackles, and World Rugby has published guidelines that professional teams should limit full-contact training to 15 minutes a week; in rugby league, the game-wide introduction of mouthguards that can detect if a player is at risk of concussion or head trauma, has recently been approved; while in American football, where retired NFL players have already received $821m in compensation for neurocognitive problems, a raft of rule-changes have been introduced in an attempt to minimise head injuries.

In the case of cricket, where the rock-hard ball rather than the opponent is the most obvious threat, short-pitched bowling has come under the spotlight, with the Australian writer Malcolm Knox arguing that the demise of the bouncer is inevitable. “It will hurt cricket to lose the bouncer, but the bouncer is hurting cricket more,” he wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald in December 2020. “Twenty years from now, we will be wondering how the practice of aiming a projectile at a player’s head was allowed to go on so long.”

Knox was ridiculed by some, with former Australia coach Mickey Arthur among those to slap down his suggestion on social media, but he was reflecting a view that is gaining wider traction. A month after the article was published, the MCC announced a “global consultation on whether the law relating to short-pitched deliveries is fit for the modern game”, emphasising the need to remain in-step with the latest research into concussion in sport.

While advancements in helmet safety – most notably the widespread use of neck guards and the narrowing of the gap between the top of the grille and the peak – have reduced the likelihood of the type of serious injury which took the life of Phillip Hughes in 2014, they do not rule out the risk of concussion. In fact, Tom Milsom, managing director at Ayrtek, one of the world’s leading helmet manufacturers, believes the revision of UK helmet safety standards in 2013 – which included the addition of a projectile test to assess whether the grille or ball would come into contact with the face or head upon impact – may have contributed to an increase in the frequency of concussions.

“The new regulations solved one problem but created another,” says Milsom. “We had the ball going through the peak and the grille, and the helmet had to be made stiffer to stop it flexing. But by doing so we made a harder, heavier, more rigid shell and now it’s like a snooker-ball effect, where the cricket ball hits the helmet, and the helmet passes the force on to the head inside of it. We stiffened everything up as a result of using materials which are designed not to flex as much.”

Speaking to the Telegraph last year, Dr Michael Turner, the medical director and CEO of the International Concussion and Head Injury Research Foundation, said: “Helmets are designed to prevent skull fracture but do not stop concussion. The way forward is to prevent concussion taking place – by changing the rules if necessary.” He went on to argue that a ban on short-pitched deliveries should be considered in junior cricket. “The outcome is likely to be more severe in younger brains. The evidence is that the younger you are when you get a concussion, the more likely you are to have long-term problems with it.”

For cricket to be viewed as an attractive sport for youngsters and hold its own in terms of participation figures, it’s imperative that parents feel it is safe. But Turner’s suggestion does pose the question: if emerging cricketers have no experience of facing short-pitched deliveries at junior level, how will they cope when faced with a barrage of bouncers when they make the step up?

Ian Chappell, who claims he never got struck on the head across his 20-year professional career, batting without a helmet for the vast majority of it, insists that “technique is the best way to avoid getting hit”. Without an early grounding in how to counter short-pitched bowling, there is surely a risk that players would end up getting hit more at professional level, and that the frequency of concussions would climb more steeply.

So is a game-wide ban on the bouncer a realistic possibility? The MCC say they are “collating feedback” from their consultation. Judging by the response to the announcement of the review, there is very little appetite for significant change within the cricketing fraternity. “Players around the world are strong on the bouncer continuing to be a part of cricket,” said Tom Moffat, chief executive of the Federation of International Cricketers’ Associations. “It’s a key aspect of the fabric of the game and assisting the balance between bat and ball.” John Snow, the former England fast bowler, echoed that point, writing in the Mail: “It becomes a totally different game [if the bouncer is banned] … you might as well stick a bowling machine at one end to let go of it.”

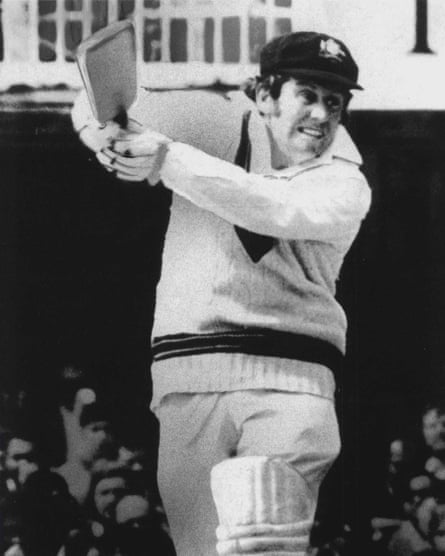

Former opening batter Andy Lloyd, who was infamously pinned by a brute of a delivery from Malcolm Marshall on his Test debut in 1984, and permanently lost around a third of his central vision in his right eye as a result, is also adamant that bouncers remain essential to the game, despite the risk involved. “I definitely don’t think the bouncer should be outlawed, definitely not,” says Lloyd, who was sidelined for several months and never played for England again. “Crikey, it’s hard enough for bowlers anyway these days. They need to have some kind of alternative to just the good length ball and the slower ball. I think the rules on bouncers are good and fair and should be retained.”

Gary Kirsten, another opening batter who received plenty of chin music across his career, is equally firm on the issue, but he does accept that more could be done to improve player safety. “If you take away the bouncer you take away the game’s integrity,” says the former South African left-hander. “But what will happen, and should happen, is that there will be more regulation around equipment and safety measures. I cringe watching people batting in the nets these days. It’s one thing getting hit on the head in a match but go and watch a net session.

“They’re going to have to keep ramping up the regulations. But, bottom line, I don’t think you can shift the integrity of the game, especially in red-ball cricket. That would be a dangerous play. It won’t be banned from the game.”

Bouncers are viewed as so integral to cricket, and to the Test format in particular, that it’s almost impossible to imagine the game without them. It would be a much duller, flatter spectacle. Duels such as Donald v Atherton, Lee v Pietersen, and Lillee v Fredericks created some of the sport’s most enduring and iconic images, and the danger in those battles helped to make them so electrifying. But there is a balance to strike, particularly with the possibility of legal action on the horizon as the issue of concussion in sport receives wider coverage.

“If you don’t want to get hurt, then don’t walk through the gate,” argues Ian Chappell – but the reality is more complex than that. The game has no desire to outlaw the bouncer, but it may reach a point where it cannot afford to keep it.

This article was published first in Wisden Cricket Monthly. Guardian readers can get three digital issues of the magazine for just £2.49 or three print issues for just £5.99.