A feat of detective work – plus the chance discovery of dozens of well-preserved documents at a wrestling club in Wigan – has unlocked a remarkable secret that rewrites more than 100 years of British Olympic history, the Guardian can reveal.

The sprinter Harry Edward, who won two bronze medals at the 1920 Antwerp Games, has long been lauded as Britain’s first black Olympian. But now a team of researchers has found that Edward’s achievement was beaten by 12 years by a long forgotten black heavyweight wrestler named Louis Bruce, who reached the second round of the 1908 Olympics in London.

Bruce, who was born in Edinburgh in December 1875, is already known to transport historians as one of the first black tram drivers in Britain. Last year he was celebrated by the London Transport Museum and appeared on its Black History tube map. Until now, however, his sporting claim to fame has been ignored.

That will change with the British Olympic Association acknowledging the significance of the findings. Scott Field, the BOA’s director of communications, told the Guardian: “This is a fascinating new body of research and we’re excited to learn of Louis Bruce’s story in being the first reported black British Olympian. The diversity of British Olympians is to be celebrated and something we are incredibly proud of.”

Quick GuideHow do I sign up for sport breaking news alerts?

Show

- Download the Guardian app from the iOS App Store on iPhone or the Google Play store on Android by searching for 'The Guardian'.

- If you already have the Guardian app, make sure you’re on the most recent version.

- In the Guardian app, tap the Menu button at the bottom right, then go to Settings (the gear icon), then Notifications.

- Turn on sport notifications.

The discovery also establishes Bruce as the sixth earliest known black athlete to compete at an Olympics. The first was Constantin Henriquez, who played rugby for France in 1900. The US hurdler George Poage and two South African marathon runners, Len Tauyane and Jan Mashiani, competed in 1904, while the American 400m runner John Baxter Taylor Jr first raced on 21 July 1908, two days before Bruce wrestled in the 73kg catch-as-catch-can wrestling division.

The seeds of the tale were sown last year when the Canadian researchers Connor Mah and Rob Gilmore, who contribute to the Olympedia.org website, the most comprehensive database about the Olympic Games, began to clean up official athlete records from London 1908.

The first hurdle they faced is that many competitors’ full names were not included in the official records. In Bruce’s case there was a further complication as he was erroneously identified in some history books as “Lawrence Bruce”.

“A major problem we had is that many official Olympic reports, along with newspaper coverage, rarely used more than a first initial and a surname for the athletes,” said Gilmore, who worked at the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick for nearly 40 years. “This also seemed almost an iron-clad rule in sports journalism at the time, especially with amateur athletics.”

However during their research Mah began to wonder if Bruce had been misnamed, and also noticed from census archives that a Louis Bruce was in Hammersmith around the same time as the 1908 London Games. Meanwhile Gilmore found a wrestling advertisement in the newspaper archives a year later for a bout featuring Ernest Nixson and a “Darkey” Bruce, as well as multiple clippings describing him as “coloured” which further piqued their interest.

But the breakthrough came when it was suggested to Mah that the Snake Pit wrestling club in Wigan had a collection of old wrestling documents and memorabilia, which had been passed from person to person down the years and might be worth exploring. It proved a eureka moment.

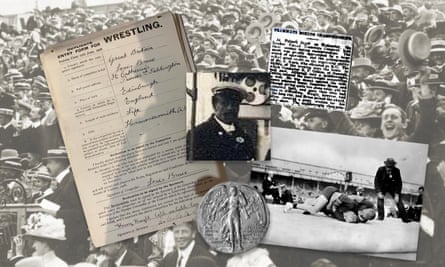

When Mah contacted the club, he found it had a set of 1908 Olympic wrestling documents, including entry forms and lists, which included the full names and addresses of all 53 British wrestlers in the competition. That allowed him and Gilmore to establish that L Bruce’s first name was Louis, not Lawrence. And, shortly thereafter, that his address, 76 Princes Road in Teddington, was the same as the tram driver Louis Bruce listed in the 1911 UK census.

Mah said: “All we knew about him before we started our research was that a ‘Lawrence Bruce’ was affiliated with Hammersmith Amateur Wrestling Club and that he competed in the heavyweight division of the 1908 Olympics, defeating Alfred Banbrook in the first round, but losing his next bout to Ernest Nixson.

“Over the few months of digging we were able to make significant progress, but it was the set of documents at the Snake Pit club that provided the breakthrough. Especially as they provided the full names of every single competitor, in their original handwriting and the street address of each competitor.

“The person there sent photos of all the documents they had via WhatsApp after I vaguely described what I was looking for. I had no idea that they had everything – it was a huge stroke of luck.”

That was far from the end of the story. The pair were then helped by the sports historian Andy Mitchell, who discovered further details about Bruce’s extraordinary life – including his birth certificate and a photograph of Bruce on a tram from 1906, confirming beyond doubt that he was black.

In the picture Bruce – who got his licence to drive trams in 1900 and was later promoted to inspector, a notable achievement for the time – stands alongside the mayor of Kingston upon Thames, Henry Charles Minnitt, as he ceremonially takes the controls of the first London United Tramways electric tram to cross the Kingston Bridge over the River Thames as a part of a new route to Tolworth and Surbiton.

As well as his regular duties, Bruce was the personal driver for the managing director of the company, Sir James Clifton Robinson, who had a private tram at his house for commuting to work.

In 2021 Transport for London and Black Cultural Archives celebrated Bruce’s achievements, calling him “one of London’s first Black tram drivers” – although they too got his first name wrong, calling him Lewis not Louis. “Unfortunately, little further is known of Lewis’s story,” they wrote.

Since then, the researchers have uncovered far more about Bruce’s life, including the fact he frequently performed in entertainment acts as a dancer, ragtime singer and comedian in tramway social events and concerts.

During that period he married Ethel Elizabeth Dunn in September 1911, and the couple later had a son, Dennis. Bruce may have worked on the trams as late as 1922, but by the 1930s he owned a newsagent shop in Epsom Road, Sutton.

Meanwhile Bruce’s sporting achievements continued after the 1908 Olympics. In January 1913 one report noted that “the well-known coloured boxer” Inspector Bruce had won the London United Tramways heavyweight title, while a year later he also claimed victory in a one-mile walking handicap race at Griffin Park.

The Olympic historian and statistician Hilary Evans, who helped with the research, said Bruce’s story was highly significant: “In this day and age it’s very unusual to find a motherlode of documents that haven’t been examined by historians.”

Bruce died, aged 82, in 1958 with an estate valued at £5,897. One mystery remains. His birth certificate states that Louis Bruce McAvoy Mortimore Doney was born in Edinburgh to Jane Elizabeth Doney, who is believed to have been white. However, his father is not named.

Intriguingly, Doney was a widow who had six daughters in Plymouth before giving birth to Bruce in Scotland – yet she was back in the south-west and remarried by the time of the 1881 census. Bruce then grew up in Plympton, Plymouth, with his grandmother and two aunts.

On his marriage certificate, Bruce listed his father as a medical practitioner named William King Bruce, but researchers are yet to find him.

“The only thing missing, frustratingly, is the identity of his father,” says Mitchell. “That discovery will go some way to explaining why a 33-year-old widow from Plymouth with six daughters ended up having an illegitimate child in Edinburgh.”

It all makes for a remarkable tale, which adds to the rich tapestry of British achievements since the modern Games began in 1896. Next month at the Winter Games in Beijing, 50 Team GB athletes will seek to write their own chapters in Olympic history. Now, at last, Bruce’s story is also being heard.