Kevin Dugar got a letter from his brother.

It was fall 2013, and Kevin hadn’t seen his identical twin Karl in years – they were both serving time in different Illinois prisons. A murder conviction all but guaranteed Kevin, 36, would remain incarcerated well into his 70s.

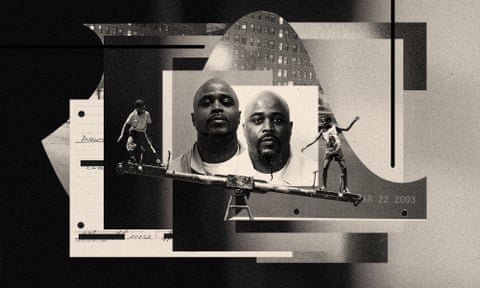

As kids, the twins had been inseparable. They would dress in matching outfits, making it difficult even for family to tell them apart. They would sometimes switch places to fool their teachers and friends. And in their 20s, while selling drugs on the streets of Chicago, they would both be known by a single nickname: “Twin.” They had a special brotherly bond, an unspoken promise to always have each other’s back.

By the time Kevin received the letter, he had been languishing in decrepit conditions for years. When it rained, water would drip from the ceiling. In the summer, heat got so unbearable that Kevin would revel in the air that flowed through the crack at the bottom of his cell door. He described prison like a dog pound, except for one difference: people care more about dog pounds.

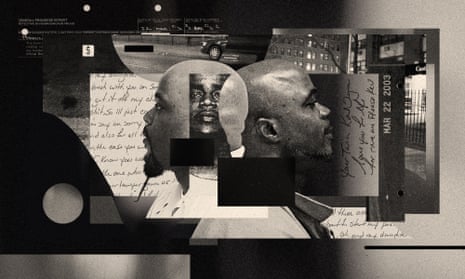

Karl’s letter started with updates about his life. “I’m about to start my post conviction in a minute,” his brother wrote. “Hopefully I get some rhythm. Oh and my daughter is about to enter high school soon.”

But the tone quickly changed, and Karl’s neat script, scrawled in black pen, began to scrunch together like he was racing to get to the end.

“Look Kevin, I’m beating around the bush with you on some shit I’ve been keeping a secret for years, and I have to get it off my chest before it kills me.

“First off, I’d like to say I’m sorry for all these years you’ve missed out of your daughter’s life and also for all the pain you’ve endured over the last decade or so.”

“You know the case you were found guilty on and you swore you were being set up on? I know you was telling the truth … I’m the reason your life got fucked up.”

The cops, he went on to confess, had grabbed the wrong twin.

“Look Kevin, please don’t tell Momma or Dad. Let me be the one to tell them.”

Eight years before he read that letter, Kevin was handed a 54-year sentence for the killing of Antwan Taylor, a member of the Blackstones street gang. Kevin had been a member of a rival gang, the Vice Lords, though he had been desperate to leave that life behind.

Kevin had always claimed his innocence. He even declined a generous plea bargain, refusing to admit to something he did not do. But one thing never left his mind: that his twin could have been the culprit. He’d even asked him 10 years ago, as he sat in jail awaiting trial.

Karl had denied everything, and Kevin believed him.

In the end, what brought Kevin down was a stack of Polaroids, and a system willing to convict based on the testimony of a single eyewitness.

Mistaken identifications are one of the leading causes of wrongful convictions. Almost 30% of the convictions of innocent people recorded by the National Registry of Exonerations were influenced by inaccurate eyewitness IDs.

Still, eyewitnesses are routinely used as primary evidence in US courts. Sometimes, as in Kevin’s case, they are the only evidence available.

Despite their fallibility, they remain pretty convincing to the average juror – even though we know human memory to be unreliable, especially when tasked with recalling traumatic events. Shock, poor lighting and the time between a crime and the official identification are several factors that can degrade the accuracy of our memories.

And then there was Kevin, who had the most glaring complication to a case hinging on eyewitness accounts – an identical twin.

Somehow, investigators were able to push that inconvenience aside.

Both brothers were introduced to the criminal underworld at a young age by their cousins, who were members of the Vice Lords.

At only nine years old, Kevin recalled being fed glorified tales of violence and cold-hearted revenge. “Our older cousins were doing everything under the sun to bring money in,” Kevin wrote to me from prison. Robberies and drug deals were the norm.

The twins’ father, Isaiah, worked as a long-distance truck driver. Their mother Judy was often left alone to raise the twins and their two sisters. It was a fight for survival, and the Dugars needed to eat. “We wanted to help my mom out,” Kevin wrote. “There was no Santa and shit coming to the hood.”

Kevin and Karl started building their records at 17 for offenses ranging from street fighting, disorderly conduct and gang loitering (the supreme court found Chicago’s anti-gang loitering law unconstitutional in 1999, which the ACLU called “a meaningful victory for young men of color” since the law gave police power to arbitrarily select people to arrest).

After high school, Kevin started working as a barber while selling drugs on the side. In January 2000, officers caught him selling crack on a street corner. He was sentenced to four years.

By the time he was released, Kevin, now 25, was tired of the gang lifestyle. He wanted out, and it was high time to make an exit: in the early aughts, Chicago had more homicides than any other city in the nation. Chicago police were cracking down on gangs with such force that the number of homicides dropped from 598 in 2003 to 447 in 2004 – the lowest since 1965. Kevin knew he’d be a target back on the streets.

He also couldn’t stop thinking about a young woman he had fallen in love with.

Kevin had met Rosalina Rosa in high school. One day, feeling bold, he had engaged her in conversation and was quick to grab her heart.

“Kevin was the love of my life,” Rosa told me. “He was so strong. He was so handsome. He was what every girl wanted, you know what I mean? … He was a protector. He always took good care of me. And he was a mama’s boy. Outside on the streets, he was very tough. At home, he was a mama’s boy who loved her mac and cheese.”

Rosa moved to Pennsylvania in 2000 to be with her sister, who was undergoing cancer treatment. It was supposed to be a short trip, but she fell in love with the pleasant pace of life in the countryside. She thought this new life could be an escape for Kevin too. “I said, if you really want to change and you’re serious, then come out here.”

Kevin applied to parole in Pennsylvania, but his request was denied. This wasn’t going to stop him from seeing his beloved. In February 2003, a few weeks after his release from prison, Kevin boarded an Amtrak train using his brother’s ID and moved in with Rosa in Souderton, 30 miles north-west of Philadelphia. Karl covered for his brother by impersonating Kevin on the phone with his parole officer.

In Pennsylvania, Kevin finally felt free. He had always believed the Vice Lords would lead to his death and would often picture his body left somewhere on the streets of Chicago – just another dead gangster shot by the cops or over some drug business. For the first time in his life, those dark thoughts went away. Kevin imagined a normal life with Rosa: marriage, kids, a stable and peaceful home in suburbia.

But then Kevin got a call from Karl saying his parole officer wanted to meet in person.

Rosa was nervous about Kevin returning to Illinois. She tried to get him to blow off his parole. “That’s how bad the streets were in Chicago at the time,” she said. But Kevin was worried his brother wouldn’t pass a drug test if Karl went to the in-person meeting. He was also hopeful a good impression would give him an opportunity to legitimately parole in Pennsylvania.

On 16 March, Kevin got on a train to Chicago to meet his parole officer. That was the last time he and Rosa would see each other outside prison walls.

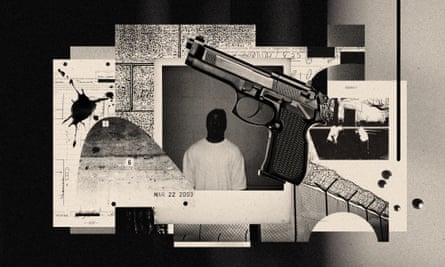

The night Antwan Taylor was killed began with a routine Saturday night stop at the corner store to buy blunt wraps. It was a dicey spot to visit, right in the middle of disputed gang territory in Uptown Chicago where the number of altercations between Blackstones and Vice Lords seemed to be rising.

Not long after Taylor stepped out of the store, a man dressed in black came running down the street and shot him.

Taylor’s friend, 24-year-old Ronnie Bolden (a fellow Blackstone), was outside with his 16-year-old girlfriend Monique Boykins. She ran to a nearby apartment building, calling out for help.

Bolden tried to run, too, but was shot down in the middle of the street. He thought he was going to die until he heard the shooter’s gun jam: “Click, click.” Then he saw the man in black run away through a nearby park.

Taylor, his blue tracksuit soaked in blood, died at the scene.

Investigators arrived at the hospital hours after the shooting to interview Bolden. He was recovering and in relatively good shape, considering he had been shot in the back. Bolden said the shooter was Black, male, maybe a Vice Lord; he could identify him if he saw him, but didn’t know his name.

Boykins, only a sophomore in high school, was immediately brought into the police station from the scene. She didn’t have much information either. All she knew was the shooter was wearing a black hoodie and black jeans.

Leads were slim, so a month later, Chicago PD’s narcotics team conducted undercover buys on Vice Lords to get a few of them into custody to interview.

One of them was Melvin Hughes, who happened to run into Taylor in the corner store moments before his death. When he exited the store, Hughes saw a guy dressed in black running down the street towards Taylor. He had recognized him as a Vice Lord called Twin.

The day after Hughes’s interview, on 24 April, Bolden identified Kevin as the shooter from a photo array. In a signed statement, he said he knew Kevin and his brother for about 15 years, but he hadn’t identified Kevin earlier because he was afraid he would get killed by Vice Lords for snitching.

On 28 April, the young Boykins, nervous and unsure among the men bearing badges, was asked to view a lineup. Kevin, who had been brought in, shook his head as he looked at his own reflection in the one-way glass. “Please, I didn’t do it, don’t put me in jail,” he pleaded. The other guys in the lineup looked at Kevin like he was crazy. He said it again, even after a detective ordered him to shut up.

Boykins picked out Kevin.

Kevin needed an alibi, but he couldn’t remember if he had returned to Chicago before or after the shooting. This was pre-smartphones; he could not check his calendar while he was being grilled. A lawyer would have kept Kevin quiet so he could straighten out the details, but he didn’t have one. He was nervous, so he kept talking. First he said he was home with his mom, thinking that was the safest answer. Plus, it was better not to admit to breaking parole in Pennsylvania.

But Rosa had gotten word that Kevin was in custody. In an effort to help, she called the lead investigator and told him her boyfriend had been in Pennsylvania when the shooting occurred. When asked about it, Kevin admitted to traveling to Pennsylvania and said he lied because he knew it violated his parole.

This slip-up handed the detectives what they needed. Not only did it seem like Kevin couldn’t keep his story straight, but police could lock him up for the parole violation.

What Kevin didn’t realize until it was too late was that, on the night of the shooting, he was at his parents’ house attending a birthday party. He did have an alibi – but it was too late to use it.

Kevin spent two years in county jail before he went to trial – he could not afford the bond on a $2m bail. His defense attorney Charles Piet wanted him to take a deal: plead guilty to second-degree manslaughter, get 11 years, and be released in less than three with credit for time served and good behavior.

Kevin flat-out refused. “I don’t take a plea for shit I didn’t do,” he told me. “I wouldn’t have cared if the death penalty was up on the table, I would’ve been one dead n**** and you can quote that!

“When I didn’t accept the 11 years, my attorney at that time was pissed at me. He threw everything he could at me and, hell, he even said ‘you’ll never get to sleep with women again.’ Yeah, he went there.”

Three more years behind bars would have been nothing compared with more than five decades in prison. Kevin was only 27 and a new father (he and his ex-girlfriend got pregnant from an affair not long before he was arrested). A plea meant Kevin could have been out to see his daughter grow up. He might have had a chance at turning his life around.

But he would not – could not – admit to a crime he did not do.

“I wasn’t hearing shit,” he told me. “I was ready for trial.”

This whole time, Karl was harboring his secret. He frequently visited his brother in jail, standing by him every step of the way – or so it seemed. He could have ended the trial before it even started, but never had it in him to tell the truth. He knew Kevin was innocent, so why wouldn’t the jury see it that way too?

On the day of the trial, Boykins, who by now was 18, recalled Bolden threatening her months earlier, putting pressure on her to tell the court Kevin Dugar was the shooter.

She did not comply.

“Monique,” said Ted Adams, the state attorney. “Do you see the person who you saw shoot Antwan Taylor, do you see him here in court today?”

“I don’t know who did it,” Boykins said.

“My question, Monique, is, do you see the person who you saw shooting Antwan Taylor here in court today?”

“I see the person who I was told shot Antwan Taylor.”

“Monique, I’ll ask you one more time, do you see the person here in court today that you saw shoot Antwan Taylor?”

“I see the person who I was told who shot Antwan Taylor.”

“Judge, I ask you to instruct the witness to answer the question.”

“Ma’am, it’s either a yes or a no.”

“No.”

“Monique, do you remember after speaking to the state’s attorney, him writing out a statement recording what you told him and then you reviewing it and signing it?” Adams asked.

Her signature was on a statement, written by a state’s attorney, identifying Kevin as the shooter.

“I signed it,” Boykins said. She claimed she tried to tell detectives she didn’t get a good look at the shooter, but it wasn’t enough for them. They kept pushing other narratives. She was only 16 years old, had been at the station for hours and wanted to leave, so she agreed with what they wanted to hear.

Any doubts cast by her testimony were overcome by Bolden’s. The defense argued that Kevin could have been mistaken for his identical twin, but Bolden convinced the jurors that he could differentiate the twins, even though he admitted he never knew their real names. “I just knew he was Twin, that’s it.”

Bolden correctly identified Kevin in a photograph, and claimed he could tell Kevin and Karl apart because Kevin was supposedly heavier than Karl by about 30-40 pounds and used to have a braided beard. On the night of the shooting, Bolden said, the offender had a braided beard.

But aside from Bolden’s word, there was no evidence that Kevin had ever worn a braided beard. What the jury did not know was that someone else had a beard around the time of the shooting: Karl.

Kevin was found guilty of first-degree murder and attempted murder. Judge Vincent Gaughan sentenced him to 54 years on 10 May 2005.

The guilt of seeing his twin carted away for something he didn’t do weighed on Karl. “I was literally drinking myself to sleep every night,” he told Kevin when he first confessed.

He also started to worry the truth would get out. Not only would he go to prison, but everyone would know what he did to his brother. His paranoia overwhelmed him, until he decided to go after the one person who could betray his secret: his friend Gabriel Curiel, who was with him the night of the killing and acted as the getaway driver.

In January 2008, the two of them had a falling out over $700 Curiel suspected Karl stole from his house. Karl came back about a week later, partly to set the record straight about the money, but also to ensure Curiel would never reveal the truth behind Taylor’s murder.

Karl, flanked by two masked goons, broke into Curiel’s apartment while he and his family were home, including Curiel’s three young children. Karl and his henchmen overpowered Curiel, taped him to a chair, shot him in the shoulder, stabbed him in the chest, then choked him until he fell unconscious. They stole $4,600 from Curiel’s safe and pistol-whipped Curiel’s brother, who escaped through the second-floor window on to the roof of a neighboring preschool.

During the raid, Curiel’s six-year-old son David was shot in the head. The bullet went through his skull and exited above his left ear. Astonishingly, David survived and recovered, left with a scar on his forehead and an unimaginable trauma.

A story in the Chicago Tribune days after the incident noted the suspect’s nickname: “Twin.”

Karl was convicted of attempted murder, aggravated battery with a firearm, aggravated battery of a child, home invasion and armed robbery.

He was given a 99-year sentence.

Kevin spent years unsuccessfully trying to appeal his conviction. The judgment was affirmed in 2007. Kevin then filed a petition to appeal in the Illinois supreme court, which was denied in January 2008. That summer, he filed a post-conviction petition, which was also dismissed. In 2010, he filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus, which was – of course – denied.

Then, a decade after the shooting, Kevin got the letter from his brother.

“I know you’re all fucked up reading this right now and you should be.” Karl wrote. “I could’ve told you what I did a long time ago. Bro I was scared to lose you lil brother … I was selfish … Please forgive me … I’m sorry bro.”

Kevin didn’t respond to Karl’s first confession letter – he didn’t know how to. “I was so shattered,” Kevin said. He thought about the years he had lost, all the pain he endured, the fact that his daughter had to grow up without a father at home, all because of his twin brother – the man who shared his DNA.

He got a second letter a few weeks later, in which Karl once again apologized. Kevin wrote back. “I told him to write investigators, innocence projects, the works to clear my name,” he told me.

Two years later, Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions took Kevin’s case back to court to seek a new trial.

Karl claimed he went on a spiritual journey during his incarceration. “I’m a changed person. You sittin’ in the cell 24 hours a day at Menard and you think about what you’ve done. So you’ve gotta find something to bring you peace,” Karl told state’s attorney Nancy Adduci in an August 2015 interview to put his story on the record.

He recalled the night of the shooting for Adduci: around 7.30pm on 22 March 2003, after drinking and getting high at his girlfriend’s birthday party, Karl changed into black clothes and left the party at his family’s house with Curiel to go buy weed. They drove to the scene of the crime to meet a dealer, but they never ended up getting the drugs.

Karl said he saw Bolden crossing the street. Karl told Adduci: “He used to be a Vice Lord and we used to be cool, at first. And he flipped into a Stone … So that caused us a little tension.” That tension was escalated by the ongoing gang war.

He said Bolden looked like he was about to pull out a gun. “He reached for something at his waist,” Karl said, “my reaction was just to defend myself.”

“He was never pullin’ anything on you, correct?” Aducci asked.

“I know but I was paranoid. I guess I was scared,” Karl said.

“You kinda shot first, ask questions later? Is that fair to say?”

“That’s – that’s exactly what I did.”

In October 2018, after two years of consideration, Judge Gaughan shut down Kevin’s request for a retrial. He did not think Karl’s version of the events over 13 years prior lined up with the testimony of the other witnesses.

The judge also weighed the twins’ history of switching places to cover for each other. Given Karl’s de facto life sentence, the court determined Karl had “nothing to lose” by now claiming he was the shooter. Judge Gaughan speculated that Kevin and Karl were conspiring to get Kevin out of prison.

Kevin’s advocates at Northwestern kept fighting for him. Last year, Professor Andrea Lewis and her colleague Sara Sommervold brought Kevin’s case to the Illinois appellate court, trying to get Kevin a new trial. Emily Ross, one of Professor Lewis’s students from Cleveland, Ohio, was tasked with delivering the oral argument.

Ross had never argued a real case before; she had only practiced in law school moot court competitions. But the caveat of the clinic’s pro bono legal service was that it doubled as an educational opportunity for Northwestern students. This time, as she made her argument for Kevin on 18 March 2021, a person’s future was on the line.

Ross was well-studied. She didn’t just want to be Kevin’s last chance – she wanted to be Kevin’s best chance at seeing freedom again.

That wasn’t lost on the three judges. After Ross finished her argument, Justice Mary Mikva said, “I think the panel joins me in noting that Ms Ross did an outstanding job.”

Ross felt good about her performance, too. But even with the best brief and a great oral argument, she knew it was a hard case to win. The judges needed to be convinced that Karl’s confession could be enough to change the jury’s verdict – a very difficult standard to overcome.

Kevin wasn’t too optimistic either, because he knew the system wasn’t on his side. He recalled Judge Gaughan presiding over the trial of a white police officer who had shot a 17-year-old Black man 16 times in 2014. “I watched my former judge give officer Van Dyke 81 months for killing Laquan McDonald and it was caught on camera. He gave me 54 years over the word of a rival gang member.”

But in April 2021, in a two-to-one decision, the appellate court granted Kevin a new trial before a different judge. The court wrote that its decision did not necessarily rest on believing Karl, but “because it is indisputably evident that the confession could probably change the outcome”.

When Kevin got the news, he cried like a baby.

On 25 January, Kevin was granted bond. Late on Tuesday night, 44-year-old Kevin walked out of prison alongside his family and got his first glimpse of life outside in almost two decades.

But he’s not yet a free man. For now confined to a transitional facility, Kevin will wait for his official do-over. He’s dreading walking back into the courthouse – he needs to pause and take a few breaths just thinking about it.

What Karl says he did – murder, attempted murder and letting his brother take the fall for it – is unforgivable. But even after all the pain caused by his brother’s alleged actions, Kevin holds the system – and only the system – responsible.

“I love my twin brother,” he said. “It wasn’t my twin’s fault I was locked up.”

That’s not really the case, in an objective sense. But consider this: both grew up in a world where everyone was out for themselves. Kevin understands why Karl didn’t incriminate himself: that’s how you survive when you’re hustling on the streets.

The justice system, however, is supposed to serve each and every one of us with integrity. And yet it beat Kevin up over and over, betraying him at every turn.