Having an ice pack strapped to your chest – that’s how some describe the experience of taking a walk in cold weather when you have breast implants. Silicone only slowly reaches body temperature once out of the cold, so that icy feeling can persist for hours. As well as being uncomfortable, for breast cancer survivors it can be an unwelcome reminder of a disease they would rather put behind them.

Every year, 2 million people worldwide are diagnosed with breast cancer and the treatment often involves removing at least one breast. But most choose not to have their breasts reconstructed; in the UK, it is only about 30%. Now a handful of startups want to change that, armed with 3D-printed implants that grow new breast tissue before breaking down without a trace. “The whole implant is fully degradable,” says Julien Payen, CEO of the startup Lattice Medical, “so after 18 months you don’t have any product in your body.”

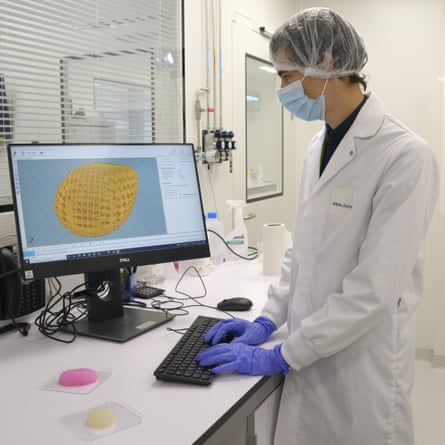

It could spell the end not only of cold breasts, but the high complication rates and long surgeries associated with conventional breast reconstruction. The first human trial of such an implant, Lattice Medical’s Mattisse implant, is scheduled to begin on 11 July in Georgia. Others will soon follow. “We expect to start clinical trials in two years’ time,” says Sophie Brac de la Perrière, CEO of another startup, Healshape.

“It’s exciting,” says Stephanie Willerth, professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Victoria, Canada, who is not involved with the companies. “As engineers, we’ve been playing with 3D printing for half a decade”, but having a clinical use that doctors recognise as useful for patients is key to getting the technology out there, she says.

But in a field fraught with difficult medical compromises, unequal access issues and expectations about what women want, the question is how big an impact the new technology will actually have.

Today, there are two main types of breast reconstruction: silicone implants and flap surgery. While implants are easy to install, flap surgery is a highly specialised business that requires a tissue “flap” being taken from the stomach, thigh or back. Surgeons often recommend flaps because, while there’s a lot of initial surgery and a longer recovery period, it gives a good, long-lasting result.

Silicone is still the most common choice. It is easy and simple, which appeals to cancer patients who either medically can’t have or mentally can’t face having tissue removed from another part of their body. But “it’s far from perfect”, says Shelley Potter, an oncoplastic surgeon at the University of Bristol and the Bristol Breast Care Centre. “It’s quite high risk. There’s a 10% chance of losing an implant.”

Silicone implants also require replacement every 10 or so years and they have had their fair share of scandals: the 2010s PIP scandal, in which a major implant manufacturer was found to have made its implants of dodgy silicone, and the 2018 Allergan scandal, in which popular textured implants were linked to an increased risk of a rare lymphoma. And as an American study from last year shows, it is mainly the idea of having that foreign object stuck inside your body that puts many off reconstruction altogether.

“So what we want to do,” says Brac de la Perrière, “is to give the benefits of the different solutions without the constraints.” In other words: the single, simple surgery of an implant, but without any lingering foreign material to cause trouble.

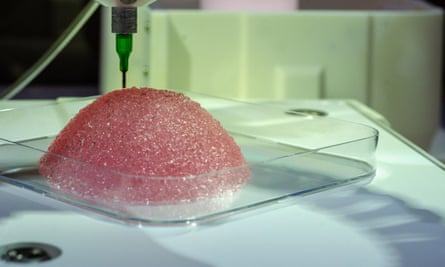

This can be achieved in different ways. Healshape uses a hydrogel to 3D-print a soft implant that will slowly be colonised by the person’s own fat cells, the initial batch of which is injected, while the implant disappears over six to nine months. The company CollPlant is developing something similar using a special collagen bioink, extracted from tobacco leaves it has genetically engineered to produce human collagen. “I think it will change the opinion of many patients,” says CEO, Yehiel Tal.

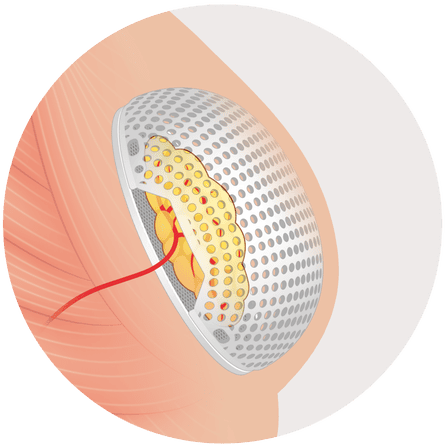

Lattice Medical has a different approach. Its implant is a 3D-printed cage made of a degradable biopolymer, in which they encase a small flap from underneath the breast area. This flap then grows to fill the cage with fat tissue, while the cage itself is absorbed by the body, ultimately leaving a regrown breast in its place.

Regrowing breasts using a cage has been shown to work in humans before, in a 2016 trial. However, it only worked in one of five women and the cages were not degradable. Andrea O’Connor from the University of Melbourne, Australia, who led the trial’s engineering team, hopes the new trial will address the problems raised in the first – for example, that patient responses can vary greatly. But if successful, it “would have the potential to help many women to achieve a superior reconstruction”, she says. Lattice Medical says its cage is an improvement because a flat base and larger pores help the tissue grow.

One big unknown is how much feeling the regrown breasts will have. A mastectomy usually means losing some sensation and, according to plastic surgeon Stefania Tuinder from the Maastricht University Medical Centre+ in the Netherlands, reconstruction affects it too. “From our data, it seems that implants have a negative effect on sensation, so the feeling in the skin is less than when you have only a mastectomy,” she says. In comparison, reconstruction from a flap with connected nerves can bring back some feeling within a few years.

Tuinder suspects the implant numbness is both because of nerve damage when the implants are inserted, and because the nerves can’t grow back once they are blocked by a lump of silicone. Whether that will also apply to the new implants remains to be seen, but since eventually there will be nothing to block the nerves, hopes are that sensation will be better.

Tissue engineered implants, however, are not the only recent innovations in the field. Many groups are working on perfecting a reconstruction technique using injections of the person’s own fat, boosted with extra stem cells to help the tissue survive. Medical professionals are still debating the safety and how the breasts hold up long term. In contrast to the new implants, the procedure might have to be done several times.

While any of these new techniques could result in something better than what’s currently on offer, Potter warns that we have a tendency to jump at new and shiny tech – an optimism bias. “We always think it’s going to be brilliant,” she says, but “we don’t want a situation like with vaginal mesh, where in 10 years’ time … we find out we have done something that isn’t helpful.”

Other solutions to the problems of reconstruction do exist. One is living without breasts, known as “going flat”. Contrary to the companies that think they can turn the reconstruction statistics around, people within the flat movement argue that if people were better informed, even more would opt out. “I reckon if [going flat] was given as an equal option,” says Gilly Cant, founder of the charity Flat Friends, “at least another 30-50% of women wouldn’t have [reconstruction].”

At the moment, the guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) says that doctors should be aware that some might not want reconstruction. But Cant says it is often presented to people as part of the treatment process. “It’s like, ‘OK, we need to do a mastectomy. Then you have chemo. Then you’ll have your radiotherapy and then we’ll do reconstruction.’ So women live for that reconstruction at the end,” she says. It comes to signal the finish line.

It is particularly contentious when only one breast is removed, because some might want the other taken off to feel and look symmetrical, rather than have a new one made. But according to Cant, many doctors don’t want to remove a healthy breast. Part of the doctors’ concern is that women will regret their decision, says Potter, but “women know what they want to do with their own bodies. We should help and support them to do what they want to do.”

Potter herself would like to see more of the ultimate alternative: not having a mastectomy in the first place. “There’s no evidence that mastectomy gives you better cancer outcomes than a breast-conserving operation,” she says. In this case, the tumour is removed but the breast is kept. For example, one of her patients had a breast reduction that removed her cancer while giving her breasts a lift. “She calls them her silver lining breasts.”

So even without tissue-engineered implants, there are enough options to make the choice a hard one. To help people choose, some charities pair up people considering a specific procedure with someone who has already been through it. At the charity Keeping Abreast, show and tell sessions give people the chance to ask the questions they might be uncomfortable asking their doctor and see the results for themselves.

But according to a 2018 report by the all-party parliamentary group on breast cancer, knowing what you want is not the same as having access to it. “There’s a massive postcode lottery,” says Potter. It stems from flap surgery being so involved that it often requires specialist plastic surgeons who can do minute surgery under a microscope. Many clinics don’t have such experts in-house and while the Nice guidance says people should still have the option, in practice it limits access.

The companies say this won’t be a problem with the new implants, because they are specifically designed to be easy to put in. Flap surgery can take from three to 12 hours depending on the flap, but insertion of Lattice Medical’s implant, for example, takes only one hour and 15 minutes. “It’s really accessible to all plastic surgeons,” says Payen.

This accessibility will no doubt be crucial in taking the new implants from a cool technology to something with real impact. But from Potter’s perspective, it’s just one potential piece in a big puzzle, not a techno-fix. The implants “would be an option for a lot of women”, she says. “But I think the main advance is all around access, proper information, giving women choice and hopefully reducing the number of mastectomies that we need.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion