An Introduction To Context Propagation In JavaScript

React popularized the idea of context-propagation within our applications with its context API. In the world of React, context is used as an alternative to prop-drilling and synchronizing state across different parts of the apps.

“Context provides a way to pass data through the component tree without having to pass props down manually at every level.”

— React Docs

You can imagine React’s context as some kind of a “wormhole” that you can pass values through somewhere up your component tree and access them further down in your children’s components.

The following snippet is a rather simplistic (and pretty useless) example of React’s context API, but it demonstrates how we can use values defined higher up in the component tree without passing them explicitly to the child components.

In the snippet below, we have our app that has a Color component in it. That Color component displays a message containing the message defined in its parent component — the app, only without having it being passed directly as a prop to the component, but rather — having it “magically” appear through the use of useContext.

import {createContext, useContext} from 'react'

const MyContext = createContext();

function App() {

return (

<MyContext.Provider value={color: "red"} >

<Color/ >

</MyContext.Provider >

);

}

function Color() {

const {color} = useContext(MyContext);

return <span >Your color is: {color}</span >

}

While the use-case for context propagation is clear when building user-facing applications with a UI framework, the need for a similar API exists even when not using a UI framework at all or even when not building UI.

Why Should We Care About This?

In my eyes, there are two reasons to actually try and implement it.

First, as a user of a framework — it is very important to understand how it does things. We often look at the tools we use as “magic” and things that just work. Trying to build parts of them for yourself demystifies it and helps you see that there’s no magic involved and that under the hood, things can be quite simple.

Second, the context API can come in handy when working on non-UI apps as well.

Whenever we build any sort of a medium to a large application, we are faced with functions that call one another, and the call stack may go multiple layers deep. Having to pass arguments further down can create a lot of mess — especially if you don’t use all these variables at all levels. In the world of React, we call it “prop drilling.”

Alternatively, if you are a library author and you rely on callbacks passed to you by the consumer, you may have variables declared at different levels of your runtime, and you want them to be available further down. As an example, take a unit testing framework.

describe('add', () => {

it('Should add two numbers', () => {

expect(add(1, 1)).toBe(2);

});

});

In the following example, we have this structure:

describegets called, and calls the callback function passed to it.- within the callback, we have an

itcall.

What Do We Want Done?

Let’s now write the basic implementation for our unit testing framework. I am taking the very naive and happy-path approach to make the code as simple as possible, but this, of course, not something you should use in real life.

function describe(description, callback) {

callback()

}

function it(text, callback) {

try {

callback()

console.log("✅ " + text)

} catch {

console.log("🚨 " + text)

}

}

In the example above, we have the “describe” function that calls its callback. That callback may contain different calls to “it.” “it,” in its turn, logs whether the test is successful or failing.

Let’s assume that, along with the test message, we also want to log the message from “describe”:

describe('calculator: Add', () => {

it("Should correctly add two numbers", () => {

expect(add(1, 1)).toBe(2);

});

});

Would log to the console the test message prepended with the description:

"calculator: Add > ✅ Should correctly add two numbers"

To do this, we need to somehow have the description message “hop over” the user code and, somehow, find its way into the “it” function implementation.

What Solutions Might We Try?

When trying to solve this problem, there are multiple approaches we might try. I will try to go over a few, and demonstrate why they might not be suitable in our scenario.

- Using “this” We could try to instantiate a class and have the data propagate through “this,” but there are two problems here. “this” is very finicky. It doesn’t always work as expected, especially when factoring arrow functions, which use lexical scoping to determine the current “this” value, which means our consumers will have to use the function keyword. Along with that, there is no relationship between “test” and “describe,” so there is no real way to share the current instance.

- Emitting an event To emit an event, we need someone to catch it. But what if we have multiple suites running at the same time? Since we have no relationship between the test calls and their respected “describes,” what would prevent the other suites from catching their events as well?

- Storing the message on a global object Global objects suffer from the same problems as emitting an event, and also, we pollute the global scope. Having a global object also means that our context value can be inspected and even modified from outside of our function run, which can be very risky.

- Throwing an error

This can technically work: our “describe” can catch errors thrown by “it,” but it means that on the first failure, we will halt the execution, and no further tests will be able to run.

Context To The Rescue!

By now, you must have guessed that I am advocating for a solution that would be somewhat similar in design to React’s own context API, and I think that our basic unit testing example could be a good candidate for testing it.

The Anatomy Of Context

Let’s break down what are the parts that React’s context is comprised of:

- React.createContext — creates a new context, basically defines a new specialized container for us.

- Provider — the return value createContext. This is an object with the “provider” property. The provider property is a component in itself, and when used within a React application, it is the entry to our “wormhole.”

- React.useContext — a function that, when called within a React tree that’s wrapped with a context, serves as an exit point from our wormhole, and allows to pull values out of it.

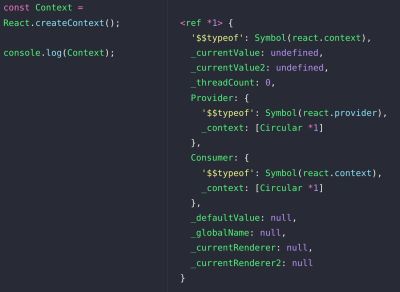

Let’s take a look at React’s own context:

It looks like the React context object is quite complex. It contains a Provider and a Consumer that are actually React Elements. Let’s keep this structure in mind going forward.

Knowing what we now know about React’s context, let’s try to think how its different parts should interact with our unit testing example. I am going to make a nonsensical scenario just so we can imagine the different components working in real life.

const TestContext = createContext()

function describe(description, callback) {

// <TestContext.Provider value={{description}} >

callback()

// </TestContext.Provider >

}

function it(text, callback) {

// const { description } = useContext(TestContext);

try {

callback()

console.log(description + " > ✅ " + text)

} catch {

console.log(description+ " > 🚨 " + text)

}

}

But clearly, this cannot work. First, we can’t use React Elements in our vanilla JS code. Second, we cannot use React’s context outside of React. Right? Right.

So let’s adapt that structure into real JS:

const TestContext = createContext()

function describe(description, callback) {

TestContext.Provider({description}, () => {

callback()

});

}

function it(text, callback) {

const { description } = useContext(TestContext);

try {

callback()

console.log(description + " > ✅ " + text)

} catch {

console.log(description+ " > 🚨 " + text)

}

}

OK, so this is starting to look more like JavaScript. What do we have here?

Well, mostly — instead of our ContextProvider component, we’re using TextContext.Provider, which takes an object with the references to our values, and useContext() that serves as our portal — so we can tap into our wormhole.

Can this work, though? Let’s try.

Drafting Our API

Now that we have the general concept of how we’re going to use our context, let’s start by defining the functions we’re going to expose. Since we already know how the React Context API looks like, we can base it on that.

function createContext() {

return {

Provider,

Consumer

}

function Provider(value, callback) {}

function Consumer() {}

}

function useContext(ctxRef) {}

We’re defining two functions, just like React. createContext and useContext. createContext returns a Provider and a Consumer, just like React’s context, and useContext takes in a context reference.

Some Concepts To Be Aware Of Before We Dive In

What we’re going to do from here on will build upon two core ideas that are important for JavaScript developers. I am not going to explain them here, but if you feel shaky about these topics, you are more than encouraged to read up on them:

- JavaScript Closures From MDN: “A closure is the combination of a function bundled together (enclosed) with references to its surrounding state (the lexical environment). In other words, a closure gives you access to an outer function’s scope from an inner function. In JavaScript, closures are created every time a function is created, at function creation time.”

- JavaScript’s Synchronous Nature At its base, Javascript is synchronous and blocking. Yes, it has async promises, callback’s and async/await — and they will require some special handling, but for the most part, let’s treat JavaScript as synchronous, because unless we get to those realms, or VERY weird legacy edge case browser implementations, JavaScript code is synchronous.

These two seemingly unrelated ideas are what allow our context to work. The assumption is that, if we set some value within Provider and call our callback, our values will remain and be available all throughout our synchronous function run. We just need a way to access it. That’s what useContext is for.

Storing Values In Our Context

Context is used to propagate data throughout our call stack, so the first thing we want to do is actually store information on it.

Let’s define a contextValue variable within our createContext function. Residing within the closure of createContext, guarantees that all functions defined within createContext will have access to it even later on.

function createContext() {

let contextValue = undefined;

function Provider(value, callback) {}

function Consumer() {}

return {

Provider,

Consumer

}

}

Now, that we have the value stored in the context, our Provider function can store the value it accepts on it, and the Consumer function can return it.

function createContext() {

let contextValue = undefined;

function Provider(value, callback) {

contextValue = value;

}

function Consumer() {

return contextValue;

}

return {

Provider,

Consumer

}

}

To access the data from within our function, we can simply call our Consumer function, but just so our interface works exactly like React’s, let’s also make useContext have access to the data.

function useContext(ctxRef) {

return ctxRef.Consumer();

}

Calling Our Callbacks

Now the fun part begins. As mentioned, this method relies on JavaScript synchronous nature. This means that from the point we run our callback, we know, for certain, that no other code will run — which means that we don’t really need to protect our context from being modified during our run, but instead, we only need to clean it up immediately after our callback is done running.

function createContext() {

let contextValue = undefined;

function Provider(value, callback) {

contextValue = value;

callback();

contextValue = undefined;

}

function Consumer() {

return contextValue;

}

return {

Provider,

Consumer

}

}

That’s all there is to it. Really. If our function is called with the Provider function, all throughout its execution it will have access to the Provider value.

What If We Have A Nested Context?

Nesting of contexts is something that can happen. For example, when I have a describe within a describe. In such a case, our context will break when exiting the inner-most context, because after each callback run, we reset the context value to undefined, and since both layers of the context share the same closure — the inner-most Provider will reset the value for the layers above it.

function Provider(value, callback) {

contextValue = value;

callback();

contextValue = undefined;

}

Luckily, it is very easy to handle. When entering a context, all we need to do is save its current value in a variable and set it back to it when we exit the context:

function Provider(value, callback) {

let currentValue = contextValue;

contextValue = value;

callback();

contextValue = currentValue;

}

Now, whenever we step out of context, it will go back to the previous value, and if there are no more layers of context above, we will go back to the initial value — which is undefined.

Another feature that we didn’t implement today is the default value for the context. In React, you can initialize the context with a default value that will be returned by the Consumer/useContext in case we are not inside a running context.

If you’ve got this far, you have all the knowledge and tools to try and implement it by yourself — I’d love to see what you come up with.

Is This Being Used Anywhere?

Yes! I actually built the context package on NPM that does exactly that, with some modifications and a bunch of more features — including full typescript support, merging of nested contexts, return values from the “Provider” function, context initial values, and even context registration middleware.

You can inspect the full source code of the package here: https://github.com/ealush/vest/blob/latest/packages/context/src/context.ts

And it is being used extensively inside Vest validation framework, a form validation framework that’s inspired by unit testing libraries such as Mocha or Jest. Context serves as Vest’s main runtime, as can be seen here.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this brief intro to context propagation in JavaScript, and that it showed you that there’s no magic at all behind some of the most useful React APIs.

Further Reading on Smashing Magazine

- “An Introduction To React’s Context API,” Yusuff Faruq

- “Reactive Variables In GraphQL Apollo Client,” Daniel Don

- “Compound Components In React,” Ichoku Chinonso

- “Useful React Hooks That You Can Use In Your Projects,” Ifeanyi Dike

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Register!

Register!