Parasites were widespread in medieval Europe, and many people died from them. This was especially common in cities, where unsanitary conditions led to frequent outbreaks of dysentery and other diseases. This was in part because people in some medieval European cities would dig holes in the ground whenever they needed to use the bathroom or dump out household waste, whereas the Romans built underground sewers.

A peer-reviewed study conducted by researchers from the University of Cambridge's Department of Archeology was published in the International Journal of Paleopathology. It is believed to be the first to compare parasite prevalence in people from a single medieval community - and so, might help archeologists determine how lifestyle changes influence one's risk of infection.

The purpose of the study was to determine whether lifestyle factors increased or decreased a person's risk of contracting intestinal parasites in medieval England. Common patterns of diet and lifestyle in monasteries, as well as among the poor population who lives outside such institutions, can be compared to gain a better understanding of life in medieval England.

The study

Founded in the 1280s, the Augustinian friary in Cambridge was an international study house, where clergy from across Europe would come to read manuscripts. It lasted until 1538 before English monasteries across England closed or were destroyed due to Henry VIII's ending with the Roman Church.

“This is the first time anyone has attempted to work out how common parasites were in people following different lifestyles in the same medieval town.”

Dr. Piers Mitchell of Cambridges Department of Archeology, lead author in the study

Researchers tested sediment samples that were taken from the pelvises, feet bones and skulls of 19 monks that were found buried at the friary in Cambridge. Samples were also taken from 25 other skeletons that were buried at the All Saints by Castle church.

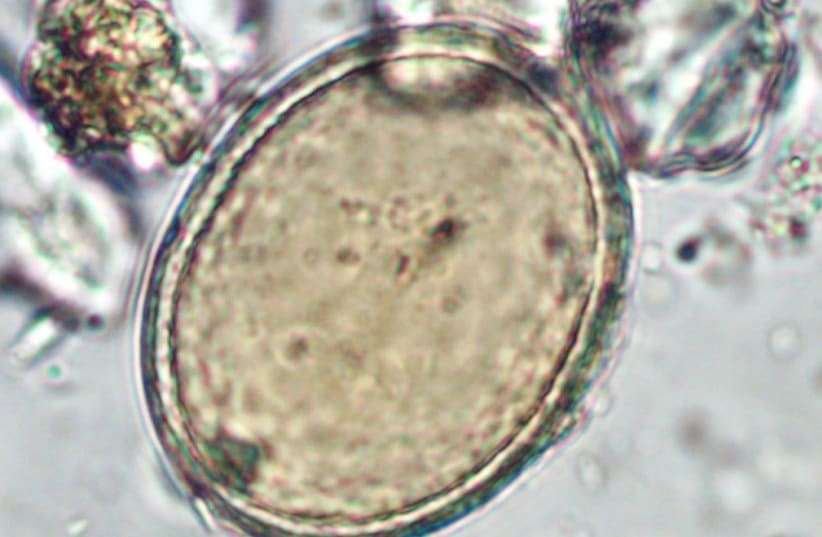

The researchers used micro-sieving and digital light microscopy to identify eggs of intestinal parasites in the sediment.

It showed that the friars had almost twice the rate of infection with intestinal parasites when compared with the general population. The researchers investigated why the disease occurred more frequently in some groups than others, and explore descriptions of intestinal worms found in medical texts circulating at Cambridge during the medieval period.

“The friars of medieval Cambridge appear to have been riddled with parasites,” the study's lead author Dr. Piers Mitchell from Cambridge's Department of Archeology said, “This is the first time anyone has attempted to work out how common parasites were in people following different lifestyles in the same medieval town.”

According to researcher Tianyi Wang, roundworm was the most common infection but there is also evidence of whipworm infection. "These are both spread by poor sanitation," Wang said.

Researchers argue that the spread of roundworm and whipworm, which is caused by poor sanitation, the difference in infection rates between the friars and the general population could have been because of how each group dealt with their waste.

John Stockton was a medical practitioner in Cambridge who died in 1361. He left a manuscript at Peterhouse college where he wrote about De Lumbricis (on worms). It states that worms are generated by various kinds of phlegm: “Long roundworms form from an excess of salt phlegm, short roundworms from sour phlegm, while short and broad worms came from natural or sweet phlegm.”

In previous studies, researchers found that people buried in medieval English monasteries had lived longer than those interred at parish cemeteries - perhaps due to better diets.