On Twitter – Black Twitter – Sydette Harry found people who resonated with her intersectional identities as a Black woman, a New Yorker, an immigrant and a member of the diaspora with family in England, Guyana and Trinidad.

But she also found other affinity groups.

“People talk about Black Twitter the way CS Lewis talked about Narnia,” said Harry, manager of communications, content and community at Mozilla Rally and an independent researcher, referring to the author’s fantasy realm of talking, mythical creatures. “They seem to believe that it’s a fundamentally different physical space.”

It’s not. Instead, it is a virtual public community, providing a counter-narrative to the mainstream coverage of Black people. It became a platform for accountability and shared solidarity, rich in culture, customs and vernacular. Being Black, Harry explains, comes with a “deep cultural well”, and Black Twitter has become a manifestation of that over the years.

“I could come into Twitter and have my talks about my burgeoning interest in Black radical philosophy,” she said. “I could talk about my love of Buffy [the TV series] at the same time, and my love of The Great British Bake Off.” Unlike sites such as LiveJournal, where separate forums are aggregated based on users’ interests, with Twitter, Harry said, “I can kind of just follow along with everything.”

Harry could fill her time with different parts of her identity because of who she followed.

Last week, the relatives of Shanquella Robinson said Black Twitter and social media were responsible for highlighting her death. Robinson, 25, reportedly died of a severe spinal cord or neck injury while on holiday in Mexico on 29 October. Mexican authorities initially ruled out foul play until an unverified video circulated on social media showing Robinson being beaten.

We can’t let this story die down! #ShanquellaRobinson #justiceforshanquella #Cabo6 pic.twitter.com/xsy3WuVmFt

— Teri Hampton (@TeriJ_Hampton) November 28, 2022

Black Twitter and other social media platforms then helped Robinson’s story go viral, prompting the FBI to get involved and Mexican authorities to investigate the case as a homicide, before charging an unnamed woman in Robinson’s death.

Twitter’s future, along with its power to draw attention to stories that are often ignored, however, is unclear, threatening to disband the cultural powerhouse that is Black Twitter. Since Elon Musk took over the company, it has laid off thousands, including engineers and entire human resources and communications teams. Product changes that reeked of lackluster planning were often quickly reversed.

An analysis by the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that racial slurs had increased in Musk’s first week in charge: there were 26,228 tweets and retweets mentioning the N-word, triple the 2022 average. This was despite Musk announcing the platform’s content moderation was “absolutely unchanged”. As some on the social media platform prepare for the next iteration of a similar digital community and debate Twitter’s successors, Black people are mostly staying put.

“We’re having the same moment of how we never actually leave the party when it’s closing down. You say you’ll leave around midnight, and you’re still there at four o’clock,” Harry says. “We’re doing that right now. And that’s because we care.”

If Twitter finally does come to a close, Harry says, she doesn’t know what the next iteration will be, but “this is a community decision”. She just hopes that what comes next will “start focusing on listening to feedback and taking care of the people who make culture … because Black folks are making culture in various nodes”.

Allissa Richardson, associate professor of journalism and communication at the University of Southern California, agrees, noting how much of the internet’s language was created by African American, Latinx and queer communities.

“There has been so much language like ‘slay’ and all these other words that we just throw around that originated in ballroom culture, and they made their way on to the internet,” she said, “and then were co-opted by elite figures or commercialized figures.”

The spirit of Black Twitter, Richardson says, will endure because there’s a real need for African Americans to connect in real time; however, “it will morph, and some of it will go underground”.

Borrowing a metaphor from WEB Du Bois, in his book The Soul of Black Folk, communication, she says, will continue to be beyond the veil, shrouded in places like barbershops and beauty salons. This, in turn, will make cultural co-optation slower.

Richardson published a book, Bearing Witness While Black, about how social media and citizen journalism through platforms like Twitter have provided Black people a platform to rewrite their narrative, highlighting the injustices they face.

She points to Emanuel Freeman, who live-tweeted the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. “That litany of tweets is iconic of Black Twitter’s turn towards activism, and towards creating a counter-narrative,” she said. Freeman shared how Brown’s body was left uncovered in the streets for four hours and tweeted about Brown’s mother’s anguish at trying to cross the police tape.

Yet, Richardson recalls, “when you turned on the TV that night, you didn’t see any of that nuance. You just saw flashbangs, fire, brimstone. Ferguson is ablaze,” cementing to Black people that if they wanted their story known, they would have to tweet or film it. While she worries about what would happen if platforms like Twitter go bust, she is also mindful of an over-reliance on social media.

“Black activists always knew that they were never wed to one particular platform to get the message out,” she says. “I think that’s the beauty of Black witnessing, is that it hacks any social network that it needs to at the time to get the word out.”

While social media has provided an avenue for Black people to alert the world to injustice and systemic racism, this is not new. Black media outlets dating back to the Antebellum period, like Samuel Cornish and John B Russwurm’s Freedom’s Journal and Frederick Douglass’s North Star, have served as an avenue for Black people, in their own words, to advocate for racial justice and emphasize racial pride. Ida B Wells, a founder of the NAACP and a civil rights activist, documented and compiled white violence against Black Americans, including more than 10,000 lynchings, in her book The Red Record. Much like how Black Twitter works today, the Black press has historically provided a counter-narrative when white media institutions failed to condemn injustices against Black people and, in some instances, even incited violence.

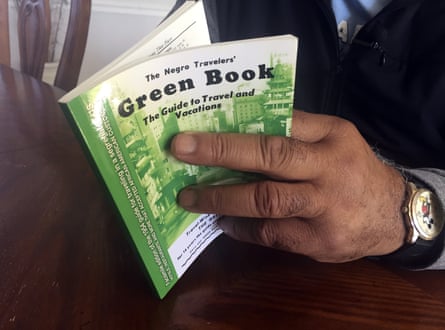

For Shamika Klassen, a PhD candidate at the University of Colorado, Boulder, Black Twitter was an extension of another piece of Black history, The Negro Motorist Green Book. It was a guidebook published in 1936 by the postal carrier Victor Green and his wife, Alma Duke, to help African Americans travel safely from the south to the north.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book functioned as a way for Black travelers to navigate racism in a physical way, read it in a book form,” she says. Black Twitter, she says, is a modernized version of the Green Book, looking beyond travel to help Black people navigate life and do it safely. While people query Black Twitter for travel tips, they are also asking about places not to go when traveling and sharing experiences of racist incidents at businesses.

In the summer of 2020, the murder of George Floyd was captured on video, shared on Twitter and other social media platforms, energized protests seeking police reform and became a political talking point. KIassen remembers feeling “beyond my end”.

“I recall going to Black Twitter for comfort, for camaraderie, for commiseration, for solidarity, all these different things,” she said.

Black Twitter also gave her a visibility she didn’t know she needed. “It’s like when you drink water, and that helps you realize how thirsty you were,” she says, describing how she felt when she saw a picture of the anatomy of a Black pregnant woman.

And that’s why she is still hanging on despite the “train wreck” that is Twitter. While the ability to create counter-narratives will be jeopardized initially as people migrate from the platform and figure out what’s next, “I’m confident that people will find a new way and likely it’s going to be another trend-setting scenario, where Black people are able to find the new pulse of the cultural digital space, and make that their own,” she says.

Quoting a tweet she saw recently, Klassen hopes that “the next place we move to we own and not rent”.