A la Ronde is a house unlike any other: a Regency building with a whimsical sixteen-sided design and wildly original interior, shaped by the travels, creativity and female solidarity of its owners.

In 1784, Jane Parminter and her cousin Mary set off across the Channel. ‘At the time it was the norm for wealthy young men to go on a Grand Tour of Europe, as part of their education, but highly unusual for women to travel alone in the same way,’ explains senior house steward, Chloe Reynolds. But Jane and Mary were lucky. Coming from a family of successful merchants, as unmarried women, they could spend their fortune as they chose.

There’s frustratingly little documentary record of precisely where the ladies went, what they did, or whom they met, but of one thing we can be sure. A decade later, laden with souvenirs and teeming with plans, Jane and Mary decided to settle near Exmouth. Here, they built a home that must have turned heads in the fashionable seaside resort nearby. With rooms shaped like slices of cake, A la Ronde’s main rooms are arranged around a central Octagon on the upper ground floor.

Stairs lead down to the kitchens and up to a first floor. From here, two further narrow flights lead to an open gallery looking down on the Octagon. ‘Jane and Mary’s bedrooms catch the morning light; the evening sunlight streams into the drawing room and dining room,’ says Chloe. ‘The idea for the faceted scheme might have come from the [octagonal] Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, which they would have visited.’

Inside, the oddly shaped spaces were put to inventive use: doors slide out of walls and tricky wedge-shaped niches are ingeniously fitted with cupboards and shelves. ‘We think a shipwright may have helped them,’ Chloe suggests. Their scheme must have challenged the craftsmen involved. Windows (some of which inspired those in the design of Shell Cottage in the final Harry Potter film) are unexpectedly placed, not in the centre of a flat wall, but on the angles. ‘You can only imagine what the joiner might have said when they told him what they wanted,’ says Chloe.

When it came to decorating the rooms, the cousins gave free rein to their passion for fashionable Regency crafts. Everywhere you look, examples of Jane and Mary’s creativity shine – they used shells to make models and decorate walls and furniture, and festooned the Drawing Room with a frieze entirely made of feathers. ‘Most of which probably came from game birds and the poultry they were eating,’ elaborates Chloe.

Furniture was painted, stencilled, or embellished with découpage. A table in the Drawing Room has a top they encrusted with stones and intaglio seals brought back from Italy. Displayed on the walls are unusual homemade landscapes of sand, mica and lichen.

They also japanned pelmets and picture frames; carefully recorded their visitors’ profiles as silhouettes and snipped intricate paperwork pictures with impossibly minute scissors. ‘To me, it says a lot that we don’t have a single portrait of the ladies but we have so much that they made,’ says Chloe. ‘They weren’t showing off their wealth, they just wanted to decorate the house themselves.’

The Octagon, at the core of the house, is a jaw-dropping space with an air of Alice in Wonderland about it. Eight fan-lit double doors, painted in trompe l’oeil marble, punctuate the walls, and the ceiling soars upwards to the roof. In the centre, a silvered witch ball, reflecting and distorting the extraordinary surroundings, dangles below a wooden dove in flight. Much of the furniture was specially designed to fit the room – benches are wedge-shaped and eccentric chairs have hexagonal seats and back splats.

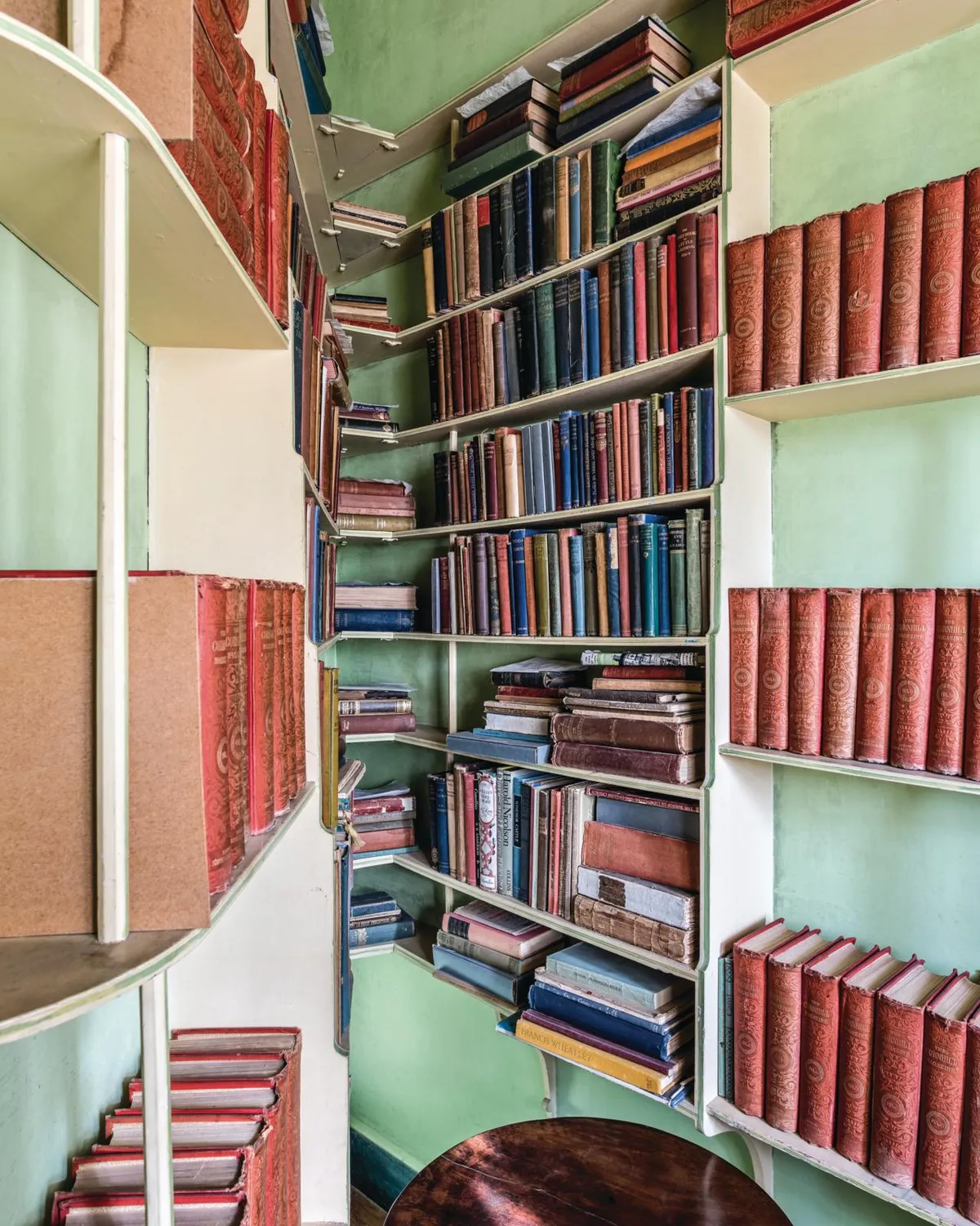

Through one of the Octagon’s doors, you enter the Library: a room dominated by the cousins’ cabinet of curiosities. Shells, rocks and fossils are arranged along with postcards, samples of beadwork, sewing accessories and Egyptian shabti figurines. ‘My favourite object is a little box that looks like a hot cross bun. When you turn it over there’s a tableau of a maid in the kitchen burning her cakes,’ says Sue Moss, A la Ronde’s volunteer conservator.

Jane and Mary’s most awe-inspiring creation is not here, in the main rooms, but suspended beneath the conical roof. The narrow stairs leading to their spectacular Shell Gallery, provide a foretaste of the treat in store, heavily decorated with gothic arches and treasures from the sea. The gallery is estimated to contain 25,000 shells, as well as minerals, feathers, twigs and bits of bone, which were pressed into lime putty to adorn niches, walls and window frames.

These days, conservation is in progress and the gallery is visible only from the landing or the Octagon below. But even glimpsed from afar you can’t fail to be impressed. ‘Shell grottos were the height of fashion at the time, but they are usually underneath buildings or outdoors. The size of this is truly amazing,’ says Sue.

Having invested so much energy in their home, Jane and Mary treasured A la Ronde as highly as their independence. According to Mary’s will, the house could only be inherited by unmarried female relatives and had to remain unaltered. But by the late 19th century, things had gone awry, and a male relative, the Reverend Oswald Reichel, moved in. The house was bought by the National Trust in 1991, and we can only imagine the cousins would be relieved to learn that for the longterm their treasured home is protected.