Few 20th-century star artists seem as much their own creation as the painter Alice Neel. While New York thrummed to abstract expressionism, then pop and minimalism, she was painting her neighbours in Spanish Harlem. They included trade unionists, wealthy art types, sex workers, poets, pregnant women, her lovers and children.

She had a caricaturist’s gift for telling details: be it the veins in a careworn Haitian mother’s hands or, in her best-known work, Andy Warhol’s scarred torso. Rarely working to commission, she described her projects as “pictures of people”, disliking portraiture’s toadying connotations. “Don’t expect to be flattered!” one sitter reportedly said.

It was only in Neel’s old age in the 1970s that her skew-whiff expressionism found acclaim in the art world. And in the ensuing decades, her star has continued to rise. Major exhibitions and comparisons to canonical greats such as Vincent van Gogh or Lucian Freud have come thick and fast. As Eleanor Nairne, curator of the first UK institutional survey of the artist in 13 years says, “it’s hard to find anyone who doesn’t go a bit weak at the knees for Alice Neel.”

With a chronological approach and fresh research – from FBI files on Neel’s communist activities to her lesser-known sitters’ biographies – the show aims to underline who she painted, and why. Nairne points to Neel’s formative year in Havana in 1925 with her Cuban husband, artist Carlos Enríquez Gómez. “It was the first time she had left the United States. She would have been among people imagining other ways of structuring societies and that would have been a big part of the conversations she was having.”

Neel’s extraordinary personal history cannot be underestimated, either; not least when Enríquez left her in 1930, taking their toddler with him. The artist had a breakdown and spent a year during which, as she put it, “I didn’t do anything but fall apart and go to pieces.” Nairne sees it as a turning point. “When people have touched that level of human vulnerability, they can have an especially charged sense of society’s responsibility to protect us all. From that moment, we see her painting an amazing array of people of different backgrounds and ages.”

In New York in the 1930s, Neel painted union marches and protests, and joined the Communist party. She also created gleefully wayward nudes, like one with her lover John Rothschild peeing in the bathroom sink while she sits on the loo. Crucially, in 1938 she moved to Spanish Harlem with the Puerto Rican musician José Santiago, away from arty Greenwich Village, which she dismissed as “honky tonk”.

The paintings she made there wil be among the show’s highlights. They depict everyday folk and their struggles – from striving mothers and their broods to Santiago’s brother suffering from tuberculosis – with penetrating psychological insight. Working from the intimate confines of her apartment, Neel developed what Nairne sees as “a collaborative process. It’s not just that Alice Neel puts down what Alice Neel sees. She created a space where people could reveal themselves.”

The dynamic changed depending on who she was working with. Her social commentary takes an inevitably different turn in her late, great work, when – as she emerged from obscurity – she invited the artists, curators and critics she increasingly mixed with to sit for her. When the critic and curator John Perreault wanted to include her work in a show of nudes, for instance, she painted him naked. “She liked putting this curator of the male nude into the position of a subject,” says Nairne.

“She often cited Gogol and saw herself as a collector of souls,” she adds. “She wanted to create an alternative canon of people she she believed deserved to be set down in paint.”

‘She’s interested in bodies in flux’: highlights from the exhibition

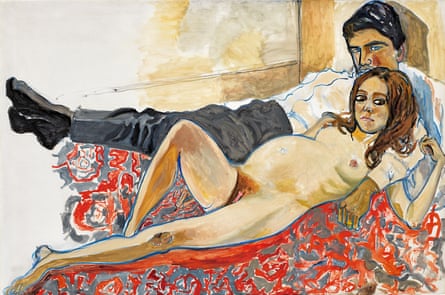

Pregnant Julie and Algis, 1967

The naked expectant mother and smartly dressed father in this painting shine a light on social attitudes to parenthood: the proprietorial man and the scrutinised, exposed body of the woman.

Self-portrait 1980

“Neel isn’t interested in nudity for nudity’s sake,” says curator Eleanor Nairne. “She’s interested in bodies in flux or extreme states of volatility or change.” This is especially true of one of her final works, this self-portrait, a rare octogenarian nude, which took her years to finish.

Carmen and Judy, 1972

This tender painting depicts Neel’s family friend and housekeeper Carmen, and her disabled daughter Judy. Carmen was a former fashion designer from Haiti, a past that’s suggested in her vivid dress.

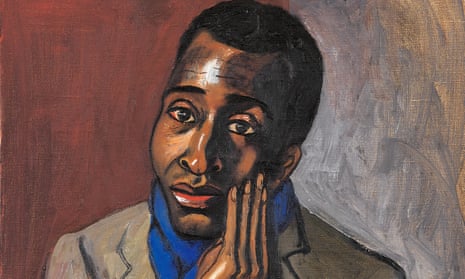

Harold Cruse, 1950

Alice Neel probably met Cruse through the Communist party, when he was working as a hospital orderly. Although this 1950 painting was created 17 years before Cruse published his seminal book The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, he is pictured as the consummate academic, chin in hand.

Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle is at Barbican Art Gallery, London, 16 February to 21 May.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion