Clay may have saved the Reverend Joyce McDonald. Addiction, abusive relationships and sex work blighted much of the first half of her life. Now, at 72, she is emerging as the celebrated artist it seems she was always destined to be. In just a few short years, McDonald’s work has been added to the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the Hammer in Los Angeles. The Brooklyn-based artist is now making her British debut – with her first solo show outside the US.

The exhibition, at Maureen Paley: Studio M in London, will include works going back to the 1990s. Mostly clay figurative sculptures, her work often incorporates other items including fake pearls, mirror and clothing. While her work is often biographical, suffused by her faith, and deals with difficult issues such as addiction and racism, there is something touchingly universal about it too. A hopefulness in dark times.

People’s reactions to her work – even her own reaction – will vary, says McDonald. “For some people, it may be sad,” she says. Others will see “peace, love, concern”. Her inspiration comes “through spirit. I can look at it, key into what it is, and I believe other people will also choose how they see it.” If there is a common theme running through her work, she says, then it is this: “Past pains, present victories.”

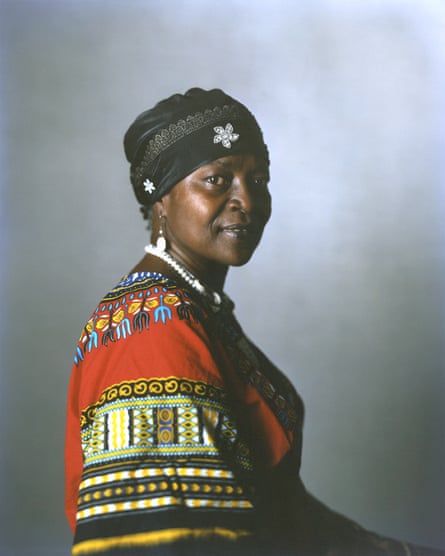

For someone who has struggled so hard, McDonald shines bright. She shoots sharp, amused sideways looks over her high cheekbones. Her easy, infectious laugh fizzes with energy. As we sit in her studio, she traces her thoughts in the air with electric blue nail polish.

At her second show, held at the local church where she is now a reverend, someone asked McDonald what kind of artist she was. The question struck her as one she needed to answer, so she prayed. “And the answer was clear as day. I heard a whisper in my spirit, ‘You are a testimonial artist.’”

She wrote her testimony down and had it laminated: “I praise the Lord for all he has done in my life,” it reads. “From the shooting gallery to the art gallery. My art not only explores the pain and hurt of my former life, but the joy and triumph of my present one. My art has helped heal old wounds and has freed me from the bondage that once oppressed my mind.”

McDonald comes from a loving, creative family. She grew up with her six brothers and sister in Brooklyn’s sprawling Farragut Houses project. Her father was a postman and keen amateur photographer who also tailored and her mother made jewellery. They both doted on her. Her mother was fond of fake pearls: McDonald is wearing a chain when we speak and many of her pieces incorporate them. Her sister, Janet, who died in 2007, was the author of Project Girl, a well-received memoir about her early life in Brooklyn, among other books. “They called us the Black Brady Bunch,” she laughs.

As a child, she drew a picture of her dad and he immediately recognised her talent. He bought her art books – Leonardo da Vinci and Picasso she thinks – that were almost as big as her. One of her most powerful pieces is a large bust of her father, a camera slung around his neck. His smile is beaming, a powerful testimony of a daughter’s love.

But a darkness descended on her early in life. After playing outside with her brothers one day, McDonald – then five years old – headed back to the family’s apartment. She got in the elevator alone. It stopped on the wrong floor and a neighbour approached her, took her to his apartment and sexually assaulted her. “We were taught to respect our elders,” she says. “It was someone I thought was a good neighbour.” She told no one. “That was the beginning of the keeping secrets.”

It was also the beginning of a downward spiral that consumed decades of her life. After dropping out of school she ran away from home and fell into an abusive relationship. Sex work and drug addiction followed and she would hang out in “shooting galleries” in Harlem, sharing needles with other heroin addicts. In 1995 she was diagnosed as HIV positive. Her doctor said she had probably been infected for years.

Her family had supported her throughout her struggles and, in 1994, McDonald’s daughters managed to convince her to go into detox. As she recovered, she started drawing. Dark drawings, she says. Then someone gave her clay to model. “Something happened!” she says, laughing and waving those expressive fingers. In her head, she heard Gene McDaniels singing his 1961 hit A Hundred Pounds of Clay.

after newsletter promotion

“All I remember is just making and making. Small figurines. I think the first I made were little clay figures of my family.” The figures kept coming and they haven’t stopped. McDonald was encouraged to show her work and won a prize at Visual Aids, a New York arts organisation that supports HIV-positive artists. The prize brought her to the attention of Gordon Robichaux, a New York gallery known for promoting under-recognised and emerging artists.

Her career took off but life’s trials have continued for McDonald. The pandemic brought back memories of the Aids crisis – at least 10 people in her apartment block died and she caught Covid three times. While McDonald was happy to see the government swing into action to tackle the outbreak, it was also a galling reminder of how little was done to fight Aids and how people still discriminate against those living with HIV. “I have friends who I have known for 15, 20 years who still haven’t told their families because of that stigma,” she says.

And like Covid, she points out, HIV has not gone away. “It is a better time to have HIV,” she says, with the improvement in medicines. But the support network for people living with the virus and access to testing and support are being reduced. “And that is not a popular conversation.”

The coronavirus outbreak came as a spotlight was also shone on another injustice – the long history of systemic racism in the US and elsewhere. In May 2020, McDonald was working on a piece based on Colin Kaepernick, the football player who kneeled during the playing of the national anthem to protest against racial and social injustice. She had been working on it for months and had just taken the piece out to work on it again when she saw the news about George Floyd, whose murder by Minneapolis police sparked global protests and fired up the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Before I knew it I had a piece of clay,” she says. “I began to go into it and I began to weep. I always feel the spirit when I am doing clay but this was like nothing else. It was very intense. That weekend, I didn’t eat, I didn’t shower, I had the same clothes on all the way to Monday.”

She showed the piece to a nephew. “What about Breonna?” he asked, referring to Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black woman shot dead by police in Kentucky during a botched drug raid.

McDonald went on to sculpt other victims of racist violence including Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Salau. When they were done, she noticed something. “All of their eyes were looking in the same direction. It was like – maybe things will get better in the future? I don’t know if they did.” She shakes her head.

Things have got better for McDonald, though. “It’s humbling,” she says. “For me it’s about spreading hope through some of the worst situations, it’s spreading the Gospel. I know without God I wouldn’t have made it through everything. I was in a detox 60 times. There’s hope after drugs, there’s hope after rape, there’s hope after kidnap. I’ve been through all of that.”

Like her clay sculptures, experience has fired McDonald, made her durable. But it has not made her hard. She says she is “amazed” by her success and hopes that her belief in art – and her faith – can be a route others too can take. “For me, my art has never stopped being therapy,” she says. “I just know when it’s the time and I go get that clay.”

Reverend Joyce McDonald is at Maureen Paley: Studio M, London, 1 June-30 July

Information and support for anyone affected by rape or sexual abuse issues is available from the following organisations. In the UK, Rape Crisis offers support on 0808 500 2222 in England and Wales, 0808 801 0302 in Scotland, or 0800 0246 991 in Northern Ireland. In the US, Rainn offers support on 800-656-4673. In Australia, support is available at 1800Respect (1800 737 732). Other international helplines can be found at ibiblio.org/rcip/internl.html

Information and support for anyone affected by addiction issues is available from the following organisations. In the UK, Action on Addiction is available on 0300 330 0659. In the US, SAMHSA’s National Helpline is at 800-662-4357. In Australia, the National Alcohol and Other Drug Hotline is at 1800 250 015; families and friends can seek help at Family Drug Support Australia at 1300 368 186