There are 15 of us crammed into a cellar beneath a nondescript house in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. To the uninformed observer, there’s nothing to see down here: just two low rooms, bare breeze-block walls, a ceiling lined with pipes. Yet we’re all looking about the place in hushed awe, like tourists staring up at the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The people I’m with are journalists, bloggers and historians, most of them specialising in table-top games, and we’re here because this is not an ordinary basement. It sits beneath 330 Center Street, the one-time home of Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax. And in February 1973 something happened here that would change the world of gaming, culture and entertainment for ever.

Across town, at the Grand Geneva Resort & Spa, Gary Con XVI is in full swing. The annual convention organised by Luke Gygax in honour of his father has been taking place every year since Gary died in 2008. It started with a few hundred devoted fans, but now several thousand come to play D&D and many other wargames, board games and role-playing games. They pack out the building’s many conference rooms and corridors, hunched in groups around large tables laden with character sheets, dice and snacks; they dress up as warriors and wizards and attend talks. Many have clearly been playing for decades.

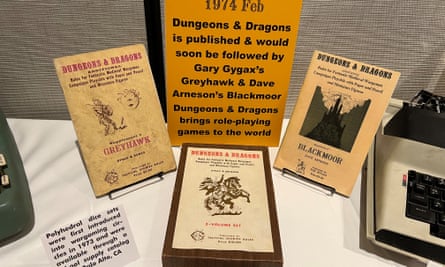

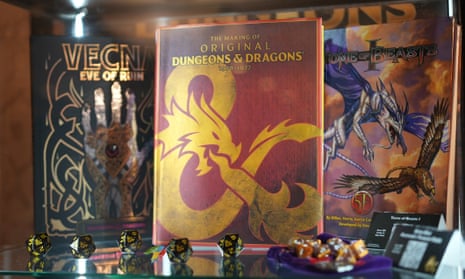

This year is special – it’s the 50th anniversary of D&D. It was early 1974 that the first edition was launched; a brown wood-grain box containing three slim rulebooks. One of the big announcements of the event is that Wizards of the Coast is publishing a range of nostalgic half-century celebrations, including two new campaigns based on classic D&D adventures from the 70s and 80s, Vecna: Eve of Ruin and Quests from the Infinite Staircase. There’s also a 500-page tome entitled The Making of Original D&D: 1970-1977, which reprints the original manuscript of D&D, complete with handwritten annotations.

What’s immediately clear is how modest and homespun the project was at the beginning. “I’ve been gaming my entire life, it’s in my DNA,” says Luke Gygax, presenting a welcome panel. “I was patient zero for D&D. In the early days at 330 Center Street, we helped to assemble the games. I tested a lot of adventures – Against the Giants, Lost Caverns of Tsojcanth, The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun – and I helped to create monsters, magic items and spells. It was just a part of playing the game with my dad.”

The Gygax home was a focal point of the wargaming community in late 1960s Wisconsin. Gary was a founding member of the International Federation of Wargamers and in 1968 he set up the society’s annual Gen Con event at the Lake Geneva Horticultural Hall. At this time, people were playing board-based wargames such as Gettysburg and Stalingrad, or miniature wargames, which used models of soldiers and vehicles on large tabletop maps. Both sought to simulate historical battles with dense rules. At his home, in the cellar, Gygax met up every weekend with his local group, the Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association, to play games and plan their own variations and rules.

Meanwhile, 300 miles away, University of Minnesota student Dave Arneson was also deep into the wargaming scene, playing a variety of games with his own highly experimental group, the Midwest Military Simulation Association. “They were already messing around with some interesting variants of a game called Diplomacy,” says Michael Witwer author of the Gary Gygax biography Empire of the Imagination and several books on the history of D&D. Diplomacy was a first world war wargame in which players each commanded the forces of a different country. Uniquely, however, it wasn’t just about combat; players also had to form alliances and secret plots. “It is a really interesting game,” says Witwer. “Lots of interpersonal activity, subterfuge and negotiation.”

Gygax and Arneson met for the first time at Gen Con in 1968. Arneson brought with him some miniature ship models he’d made and Gary was impressed. The two hit it off, kept in touch and later made a Napoleonic naval wargame together named Don’t Give Up the Ship.

But a year later, an even more important meeting took place. “It’s Gen Con 1969 and we’re down in Gary’s basement – Gary, Dave and me,” says Bill Hoyt, a member of Dave’s old gaming group who, in his late-80s, is still running wargames. “We started talking about games, what could we do with them – and the idea of medieval gaming came up, knights and castles and all that. Gary said, ‘yes, let’s do that! We’ll collect some figures, find some rules, and we’ll come back to Gen Con next year and we’ll play the game together’.”

Gary formed the Castle & Crusade Society in 1970, for gamers interested in exploring medieval wargaming. Dave Arneson joined in April. The group had its own fanzine, The Domesday Book, where they swapped ideas – vitally, they even formed their own imagined medieval realm, the Great Kingdom. They wrote to each other in character as knights and lords, informing each other of news from their areas of this fantasy domain. Already, the story-telling and character-embodiment elements of D&D were coming into play; the kernel of an idea casually bandied about in Gary’s basement was taking on a life of its own.

Gygax went on to co-create a medieval wargame named Chainmail, which created rules for man-to-man fighting with armour and swords, and brought in some innovative new ideas such as superhero characters who took a number of hits to defeat. At the same time, Dave Arneson was messing about with an experimental project named Braunstein by David Wesely, a Napoleonic wargame inspired by Diplomacy. Instead of controlling armies, players took on the roles of individual characters in the fictional German town of the title, all with their own personal objectives.

Inspired, Arneson created a campaign variation named Blackmoor, in which players worked together as individual characters to explore a medieval town, including its castle and dungeons. It brought in the concept of hit points, so that characters could take damage without dying, and used Chainmail’s combat system for fights with non-player characters. Gary read about this in Dave’s own fanzine, Corner of the Table, and asked him to come down to Lake Geneva and run a game for him and his group.

That’s how, in February 1973, Dave Arneson and fellow game designer Dave Megarry came to take the long road trip down from Minneapolis to Lake Geneva to play Blackmoor in Gary’s basement. “It seems to me, looking at the remnants of those sessions, that Blackmoor was the first game that someone from today would look at and recognise as a role-playing game,” says Witwer. “Gary’s intent was to see this Blackmoor thing that everyone was talking about and how it worked. They played all weekend, and Gary lost his mind over it – it was so innovative and different, he’d never seen anything quite like it.”

after newsletter promotion

Things moved fast after this. Determined to formalise their sketchy concept into a fantasy game that could be published, Gygax spent several weeks typing out a 50-page ruleset in his home office. He sent this to Arneson, who posted back amends. Eventually the document reached 150 pages. They had a game – of sorts. You still needed a copy of Chainmail to play it, and the many-sided dice were sold separately, but it was ready. This was Dungeons & Dragons.

The finished product was printed in early 1974. Only a thousand were made, each selling for $10. The customers were people who were already deep into wargaming, reached through fanzines and conventions. At the time, there was little money in it, but Gygax set up a company named Tactical Studies Research to publish D&D, taking a $1,000 loan from his friend Don Kaye. TSR was run from Gary and Don’s homes for a year or so as the sales trickled in, but gradually word got around about this crazy new game where you pretended to be adventurers in a medieval-themed kingdom. It found is way onto university campuses; in 1975 the UK company Games Workshop started distributing it in Europe. By the end of 1975, TSR’s turnover was $60k – by the early 80s it was $20m a year and growing fast.

“That meeting between Gygax, Arneson and Megarry in 1973 was the culmination not just of their experiences of gaming, but of decades of experimentation and game design and wargaming,” says Witwer, who later takes us on a sightseeing tour around the town. “All kinds of crazy ideas came to roost in that moment; they started piecing together things that had never been put together before.”

Before I leave Gary Con I bump into Hoyt again and our conversation almost inevitably leads back to that basement. “I travelled down to the Gen Con convention in 1974,” he says. “I met up with Dave Arneson and we went over to Gary’s house. We were in the basement and they were opening up the second printing of the game. And Dave says, ‘You want to buy one, don’t ya?’ Well, we’d driven all the way from the Twin Cities and we’d had two idiots driving – they loved to speed, so we were paying money for their speeding tickets all the way up. I had 25 bucks left for the whole weekend. But I bought it anyway.” He’s been playing ever since.

What was it, I ask him, about playing the first version of D&D in that basement that caught hold of you and wouldn’t let go? He thinks about this for a while. His mind is wandering back to that room, 50 years ago, Gary rolling the dice, Dave Arneson poring over tables of random encounters. “It’s the story – that’s the whole thing,” he says. “It’s about sharing stories. Some people can’t grab that, they’re too concrete – those people will never play. But people with imagination? Oh yeah, they’ll play … They’ll play.”

In the creative process, place is important. Whether that’s the garage where a punk band first performed together, or the bedroom in which two brothers wrote their first ZX Spectrum game, the environment feeds into whatever is made there. It is somewhat poetic then, that a game about exploring dark, subterranean spaces should have been born in a basement, long, long ago.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion