In recent years, the structure of Israeli families has undergone substantial changes including a decline in the marriage rate, a rise in the average age of marriage across all sectors, and a decrease in birth rates.

Although the marriage rate here is similar to high-income countries, the birth rate is more similar to neighboring developing countries, affecting Israel’s demographics, its future economy, and the diversity of its population groups.

A new study by the Taub Center for Social Studies Research in Jerusalem examines the connection between the decisions of Israelis about parenthood and marriage and the status of those around them. The study, conducted by Michael Debowy, Prof. Gil Epstein, and Prof. Avi Weiss, provides a tool for improving demographic forecasts at the national and local levels and for urban planning that is better suited to future family structures in the municipalities and local authorities.

The researchers focused on two social networks that could influence Israelis – their physical location and their cultural location. Researchers used data from the Household Expenditure and Income Survey conducted by the Central Bureau of Statistics between 2018 and 2020.

What social conditions impact a couple's decision to marry, have children?

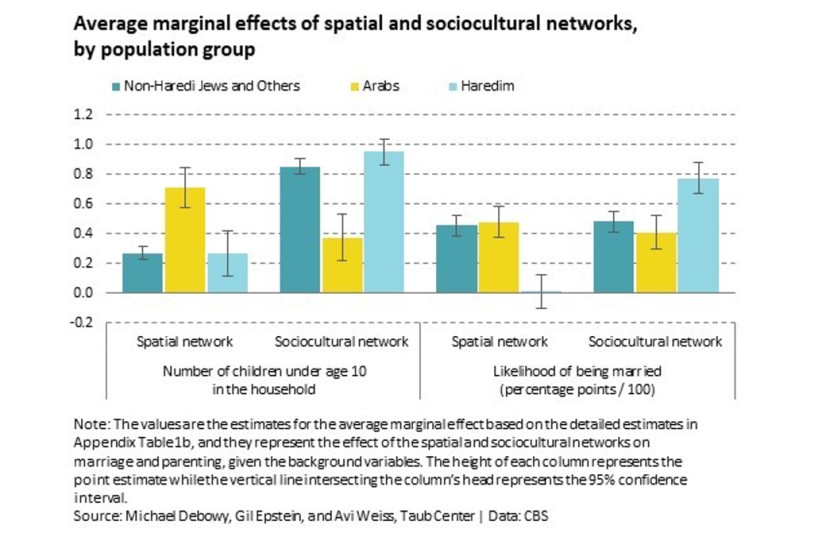

The study’s findings indicate that the greater the proportion of married couples in the individual’s spatial or sociocultural network, the greater the likelihood that the individual will be married. Thus, an increase of one percent in the rate of married people in both the sociocultural and spatial network is linked to an increase in the individual’s probability of marriage by 0.5 and 0.4 percentage points, respectively.

Environmental norms also affect the number of children in a family.

The socio-cultural network is more strongly related to the likelihood of getting married and childbearing than the spatial network. Each additional child in the average family increases an individual’s expected number of children by 0.90 and 0.25, respectively.

The researchers found that, in general, there is variation in the relative weight of local and national cultural norms across different population groups. In particular, Arabs are more aligned with their local neighbors than are Jews.

Concerning fertility, the study’s findings show that Arabs are more sensitive to the spatial network and less to the sociocultural network than are Jews and “others.” In addition, Jews who are not ultra-Orthodox (haredi) are less sensitive to the sociocultural network than haredi Jews.

Haredi or Arab family size is aligned with that of neighbors no less than the family size of non-haredi Jews.

Concerning marriage, it appears that non-haredi Jews are influenced equally by the spatial and sociocultural network, while among haredi Jews, there is no alignment with the spatial network whatsoever.

The study also examined the contribution of other variables to the likelihood of marriage and childbearing, such as education and employment. Education maintains its predictive power for marriages but less so for predicting children born. In contrast, employment predicts parenthood and marriages better.

Debowy commented that "with respect to family size, the highest correlation with the spatial network was observed in the Arab sector. In addition, cross-sector local norms are aligned with the family structure of the haredi Jews no less than in the case of other Jews, so these norms can serve as a mechanism for demographic change among various population groups as sectoral heterogeneity increases in the various parts of the country.”

Weiss, who is the president of the Taub Center, added that “care should be taken in interpreting the results since they represent correlation and not necessarily causation. If the results represent the effects of the environment on individual behavior, then our findings have significant implications regarding the planning of local and national authorities according to demographic forecasts, with emphasis on adjusting urban planning to family structures in the future.”

He added that “when predicting the needs of families in the future, local authorities need to consider both the predicted weights of different cultural groups in the population as well as their mutual influences on one another in the local space. Taking these data into account is vital to improve demographic forecasts, urban planning, and the approval of construction and housing plans, as well as the provision of public services such as education, health, and recreational spaces.”