Music, says Hattie, is supposed to be a consolation. But in the opening moments of this play, it feels more like an exorcism, as she sits down at a piano in St Pancras International station and gives a performance that goes instantly viral.

In Samuel Adamson’s latest work, two friends reconnect late in life, and what follows is a journey backward and forward through their timeline, exploring the love of music that brought them together and the events that have pushed them apart.

Jon Bausor’s set revolves (sometimes literally) around an ever-present piano, the instrument at the centre of Hattie and James’s encounters. When we first see them together they are 16-year-olds, forced upon each other by a school production of Noye’s Fludde. Sophie Thompson and Charles Edwards give delightful performances that highlights their unlikely pairing: James, his chin jutting in awkward, involuntary spasms, is a self-declared “spod”, Hattie a livewire who hides her vodka under the piano lid and declares herself “addicted to Fanny”.

She means Mendelssohn, the overlooked composer-sister of the famous Felix, and the story that unspools across seven decades is flavoured with the melancholy of lost talent as well as betrayal and broken relationships. On stage, pianist Berrak Dyer provides the music that underscores the protagonists’ meetings with sentiment and drama, and Suzette Llewellyn portrays the other women in their lives – from Hattie’s fearsome gatekeeper wife, Bo, to their respective mothers – one an upstanding member of the community, the other a daytime drinker.

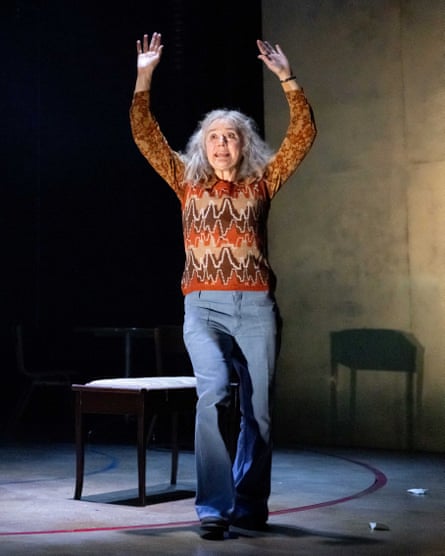

The performances elicited by director Richard Twymanare witty and expert. Thompson works her full range as Hattie, segueing expertly from girlish to grotesque to quietly dignified. Yet James, struggling with his sexuality and his envy alike, seems the more nuanced, developed character, even in a script that calls out the “soft hum” of misogyny and celebrates the lives of invisible women.

Whether the special bond between the pair quite lives up to its billing is uncertain – but the revelation of the moments that have made them, as well as the missed connections that define them, are a powerful reminder of what we owe to each other.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion