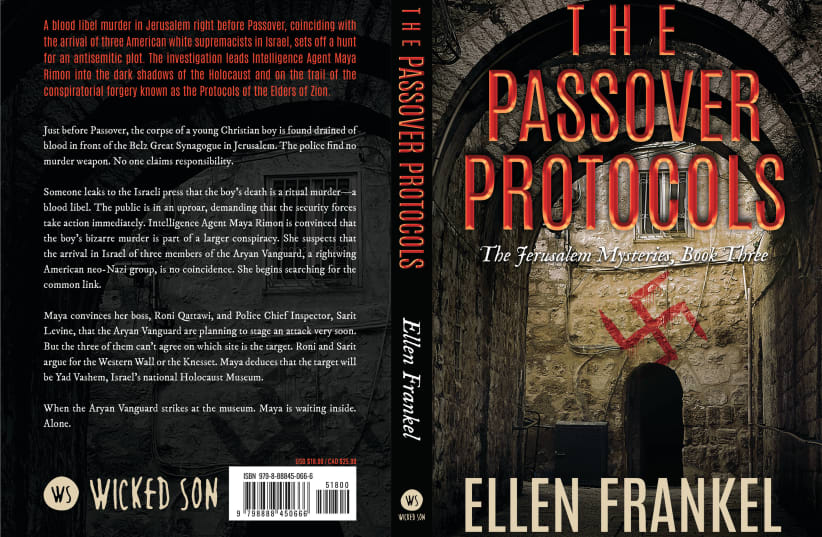

The Passover Protocols, Book 3 is the latest in The Jerusalem Mystery Series by author Ellen Frankel. The author of 11 books, Frankel served as editor-in-chief and CEO of the Jewish Publication Society (JPS) for 18 years, before retiring in 2009 and launching the series which has introduced intrepid Israeli agent Maya Rimon to the world.In The Passover Protocols, agent Rimon takes on the dark world of white supremacy and antisemitism, including encounters with The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, American white nationalists, Russian conspiracists, and the Russian mob.

Passover has long been a precarious time for Jews. In ages past, the corpse of a Christian boy would often be found on a Jew’s doorstep right before the Seder, which would trigger a pogrom. The Passover Protocols opens with just such an incident: The body of a Christian boy, drained of blood, is found outside the Belzer Great Synagogue in Jerusalem, right before Passover. Rimon and Chief Inspector Sarit Levine undertake to solve this bizarre case, which culminates in a showdown with the enemy at one of the most sacred sites in Israel.

Here is an excerpt.

APRIL 5

TEN DAYS BEFORE PASSOVER

The day dawned sunny and hot. In northwest Jerusalem, the entire Belzer neighborhood bustled and hummed in anticipation of Passover. Even the secular tourists could feel it. Aproned wives and daughters scrubbed countertops, ovens, refrigerators, microwaves, and cabinets until their fingers were raw and bleeding. Dust devils swirled in the busy streets as the Hasidic residents swept from their homes all hametz, contraband leaven outlawed on this holiday. Less than two weeks until the Seder. And there was still so much to do!

This morning Pinchus Berger arrived especially early at the Belz Great Synagogue. Despite the fact that his beloved wife Gittel Mirrel remained in the rehab hospital recovering from her recent breast cancer surgery, Pinchus still managed to get all eleven children washed and dressed and out the door. He personally took the two youngest to gan and then walked the two with special needs to their schools. Of course, he couldn’t have done it without the help of the three older girls. And his mother-in-law, Henye Ruchel, who lived with them, was also a great help, if he ignored all her kvetching and unsolicited advice.

It took Pinchus over two hours to perform his new duties in the large basement room of the shul. Crawling on his hands and knees, he swept with a turkey feather under bookcases and inside cupboards, gathering tiny crumbs in a paper bag to be burnt later together with the feather. With fevered breath, he blew away dust, which sent him into paroxysms of sneezing. Finally, he was satisfied that the basement area was absolutely leaven-free. He gulped down a glass of cool tap water to clear his throat from all the grit and cinders of a thousand chain-smokers. Then he headed up the stairs. He needed a cigarette before going to morning minyan.

As he inhaled the harsh smoke from the unfiltered cigarette, he took a moment to savor his good fortune. This was the first year that he, Pinchus Berger, apprentice watch repairman, had been assigned the holy duty of inspecting the basement matzah factory for any overlooked hametz.

He inhaled deeply to relish the last bitter tang of nicotine. Watching the tendrils of smoke rise up, his eyes scaled the enormous building that he was proud to call his family’s shul. The Belz Great Synagogue was the biggest synagogue in Israel. Some said, in the whole world.

The towering square building, its outer walls faced with alternating fluted columns and cavernous arches, immediately called to mind the grand monuments of antiquity, especially the Parthenon and Solomon’s Temple. But this synagogue was not in fact modeled on these ancient architectural wonders. Rather, it drew its inspiration from the original Belz Synagogue built in the Ukraine in 1843 by the first Belzer Rebbe, Sholom Rokeach, which had been maliciously destroyed by the Nazis.

And as if the synagogue’s external grandeur wasn’t impressive enough, visitors soon discovered that the building’s interior outshone its outer facade. The vast sanctuary seated close to three thousand worshipers. The hand-carved walnut ark, twelve meters high with the capacity to hold up to seventy Torah scrolls, had even made it into the Guinness Book of World Records.

Yet even the black-hatted regulars who attended daily prayers and celebrated in this magnificent synagogue didn’t know all its secrets. In the spring, as the holiday of Passover approached, one of the basement rooms in the Great Synagogue was quietly turned into a pop-up matzah factory. Each morning a small group of bearded Belzers in black or white coats, many with furry shtreimels perched atop their heads, trooped down to the basement to make the ritually prescribed rounds of baked wheat. Straddling both sides of a long steel table, they took turns rolling out the dough, passing it back and forth until it became large, round, and flat. They then punctured the rounds of dough with small holes, draped them over long poles, and thrust them into a fiery oven. Precisely eighteen minutes later, the matzahs emerged, appropriately kosher for Belzer seders.

This morning when he first stepped outside the building, Pinchus was immediately blinded by the brilliant April sun. At this early hour, few people walked along Binat Yisas’har Street. Most were already at prayer in the many shtieblach located in the lower floors of the synagogue. Had it not been for the scrawny yellow cat that began rubbing against his trouser leg, Pinchus might not have noticed the corpse lying at the base of the wrought-iron gate. As soon as he felt the cat’s matted fur scraping his leg, he backed up against the gate. When he looked down, he saw the body of a young boy. Horrified yet curious, he bent over, looking for signs of foul play.

He judged the boy to be in his early teens. The body was lying face up, relaxed as though asleep. The boy’s face was ghostly pale, like something hidden from sunlight since birth. There were no signs of violence.

Definitely not a Belzer Hasid. No yarmulke covering his blonde hair. No corkscrew earlocks bouncing down his cheeks or hooked behind his ears. No tzitzis dangling out of his pants. The boy’s clothes – Western jeans, a light blue tee shirt, and sandals – constituted the standard uniform of young Israeli boys these days.

And then Pinchus noticed the large gold cross suspended from a golden chain around the boy’s neck. It was not like the crosses Pinchus was used to seeing when he passed Christians on the street or sat across from them on the bus. This one had three horizontal gold bars crossing the vertical – a short one near the top, a longer one in the middle, and then another short one near the bottom of the vertical. The last bar was not parallel to the other two but angled at a slant. And on every surface of the cross were floral designs in bas-relief. What kind of Christian was he, this dead boy? And what was his corpse doing here in front of the Belz Great Synagogue? What had happened to him? And what did it mean for them, for the Belzers, that he’d ended up here?

Pinchus’s head began to spin. Would a dead body found so close to the synagogue render the holy place tamei, ritually unclean? Would they have to shut down the matzah factory? It was so close to Passover! Had the boy been murdered? By a Palestinian terrorist? Or an antisemite? Or, God forbid, one of their own, a Belzer Hasid?

Pinchus didn’t know what to do. Should he call the police? Would they completely shut down the synagogue as a crime scene? For how long? Thousands of Belzer Hasidim prayed there several times a day. Many also studied there and celebrated simchas. And what if the police discovered the matzah factory in the basement? Did the shul have a license to operate it?

Wringing his knobby fingers and moaning to himself, Pinchus swiftly made his way back inside the synagogue to look for help. He found it almost immediately in Izzy, the elderly shammas on duty that morning. As Pinchus finished blurting out his shocking tale, Izzy firmly pressed the distressed man’s shoulder and placed an arthritic finger to his own sharp nose.

“Not to worry, boychik,” said Izzy. “I will call the police right away and report it. In matters such as these, it’s always best to call upon a lower authority.” The Passover Protocols, along with the other two books in the series, The Deadly Scrolls and The Hyena Murders, are available in paperback, Kindle editions, and audio format.