The art world can be a space of wonder, beauty, bravery, connection and community. As an art critic and art historian, I’ve spent the past decade swimming in these waters. But it can also feel like a badly written joke: shaped by the 1%, populated by the shrinking middle classes, picketed by anarchists and run by unpaid interns. Perhaps “art worlds” is a better way to describe the barely overlapping spheres. It can be difficult to find the punchline among the contradictions of cleanskin wine and conspicuous consumption.

It’s this underside, riddled with friction and contradiction, which has caught the eye of two Australian authors with new books out this month: Bri Lee’s The Work and Liam Pieper’s Appreciation. So are the worlds they create for readers fact or fantasy?

The protagonist of Lee’s first novel is Lally, a young gallerist in New York navigating the death of one of her artists – a financial boon for her – and the public censure of another, who is facing allegations of sexual assault. Before the storm breaks, she meets Pat, who’s trying to make it to the top rung of a prestige auction house in Sydney by securing the holdings of an older divorcee by any means necessary.

Lee has obviously done significant research: she name-drops Jerry Saltz and Artforum, recalls the strict phone policies of the security guards at the Frick Collection and often seems to describe real-world figures. “Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons … is entirely coincidental,” her opening disclaimer states. But Lee’s fictional director of Sydney Contemporary – a bald man named Harry – sounds remarkably similar to the inaugural (glabrous) head of the art fair, Barry Keldoulis.

Yet Lee’s story also has a distinct whiff of the unreal about it. There is a narrative convenience – something of the endless finances of Sex and the City’s Carrie Bradshaw – which allows Lally to be an inexplicable cultural maven: young, beautiful, selling artworks to the Museum of Modern Art and running what we understand is the hottest gallery in New York. Mostly, this industry is a setting for the painfully facile romance between Lally and Pat; despite its studied minutiae, one never quite shakes the feeling that we’re consuming an idea rather than a reality.

Lally herself transacts in this economy of optics. In one scene, she notes that “having an Asian American with a pixie cut on the desk was a very good look for the gallery”. In another, Lally reveals she has colluded with two art critics – the worst kind of cultural invertebrates – to produce a synthetic controversy to boost hype around her show, with one claiming that they loved it and the other wanting to burn it down. In this case, my hyphenated existence as an Asian-Australian-art-critic places me a little closer to the story than most, and much of it rings false.

For starters, pixie cuts have had their day – and arts writers wouldn’t be manipulated so crudely; while susceptible to more subtle coercion and the commercial pressure that comes from publications relying on galleries to buy ads, criticism labours under the myth of its own integrity.

In the endnote of his book, Pieper makes an admission: “This book isn’t actually about art at all.” I tend to disagree. The novel is a portrait of Oli Darling: “a queer artist from the country” (his agent explains that being merely “bisexual” doesn’t play as well on press releases) whose career is built on his ability to embody the twin positions of “a true-blue Australian and a minority”. This proves to be an alchemical combination. Oli’s life is that of the charming narcissist, who constantly plays the identity politics game in pursuit of shallow virtue, and whose radicalism is public performance rather than private conviction.

Pieper also seems to have borrowed from real people to make up parts of Oli. There’s a bit of Ben Quilty’s salt-of-the-earth-Aussie-battler-everyman; something of Andy Warhol’s cultivated celebrity; and a (self-confessed) pastiche of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s aesthetic rawness. But it’s the artist, not the author, who is being derivative: Oli is that rare example of someone who should have impostor syndrome, yet doesn’t.

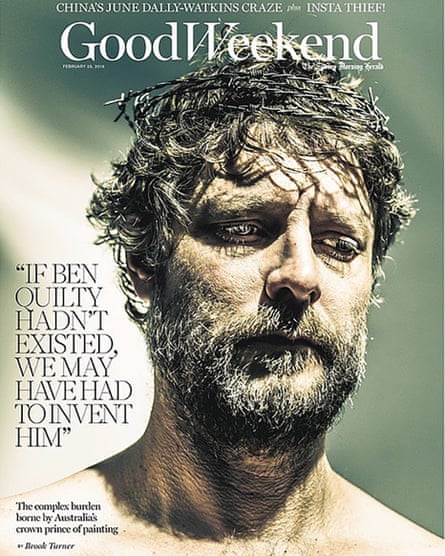

Pieper’s book focuses on Oli’s fall from grace, when he is publicly cancelled for being dismissive about the Anzacs on live TV. The reality of cancellation finds particular ground in the Australian art scene, which mixes the national pastime of tall poppy syndrome with ever-shrinking arts funding and ever-increasing competition. One only has to recall the rather theatrical image of Quilty styled as Christ on the cover of Good Weekend magazine in 2019, which stirred outrage and ironically saw him crucified by many. Pieper’s protagonist stands even less of a chance.

While Pieper is less specific than Lee when it comes to the people that populate these spaces, he’s more observant, and more playful. Oli constantly forgets the names of his interlocutors, identifying them by shorthands that underscore their utility to him, and who are recognisable to any who have rubbed shoulders in this world.

We meet “the Money”, a patron of the arts, whose unspeakable wealth has given her influence over the Australian art canon; “the Paperman”, an arts editor and critic, a recognisable gatekeeper of culture, who resents our shifting world; and “the Baron, the third-generation squatter who had inherited enormous wealth and, with it, limitless reserves of white guilt”. The names are ridiculous and the descriptions veer into the outrageous, but Pieper has captured the golden umbilical cord that connects the artist to these figures and drip feeds the creative life.

Both The Work and Appreciation paint a recognisable portrait of the art industry: its obsession with the circulation of capital, the incremental compromises made in pursuit of creative success and the puniness of the individual when confronted with the force majeure of cancellation. But it is Pieper’s book which takes this messy world beyond the understanding of art as chattel, returning a little bit of art’s magic to us.

The Work by Bri Lee is published by Allen & Unwin ($32.99) and Appreciation by Liam Pieper is published by Hamish Hamilton in Australia ($34.99)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion