How NASA Spotted The Effects Of El Niño From Space

While NASA spends a lot of time looking up and out toward the stars, the agency also has another important role: using satellites in space to look back at our own planet. Earth observation is crucial for understanding global issues like weather patterns and climate change, and seeing the big picture from orbit helps scientists get a broader overview of what is happening than anyone could get from just taking local observations.

Recently, NASA has been tracking the El Niño event, which began in 2023 and had its biggest effects through the end of 2023 and into the early months of 2024. This year's event kicked off with the hottest month ever on record in July 2023.

NASA observes the temperature using surface air temperature data collected from thousands of stations on land as well as buoy stations in the ocean. But it also uses its space satellites to observe the Earth, which gives a different view of the changing climate.

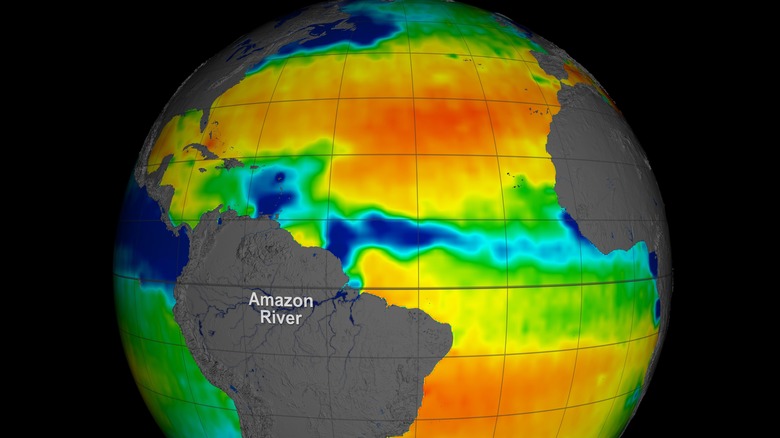

Recently, a team from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) used data from NASA's satellites to observe the level of salt in the global ocean surface, looking at 10 years of data from 2011 to 2022. By studying the salinity patterns of the ocean, NASA found changes over the decade including the warming effects of El Niño and the cooling effects of its counterpart, La Niña. Together the pair are known as El Niño Southern Oscillation or ENSO.

"We're able to show coastal salinity responding to ENSO on a global scale," said lead author of the study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, Severine Fournier, of JPL.

Seeing ocean salinity from space

The data the researchers used to study the oceans was collected from missions like Aquarius, an early sea surface salinity measuring satellite launched in 2011. It uses instruments called radiometers to see how the ocean's microwave radiation changes, indicating changes in salinity.

Since the launch of that mission, technology has improved to allow more high-resolution data from new missions like the European Space Agency's Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) mission and NASA's Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) mission.

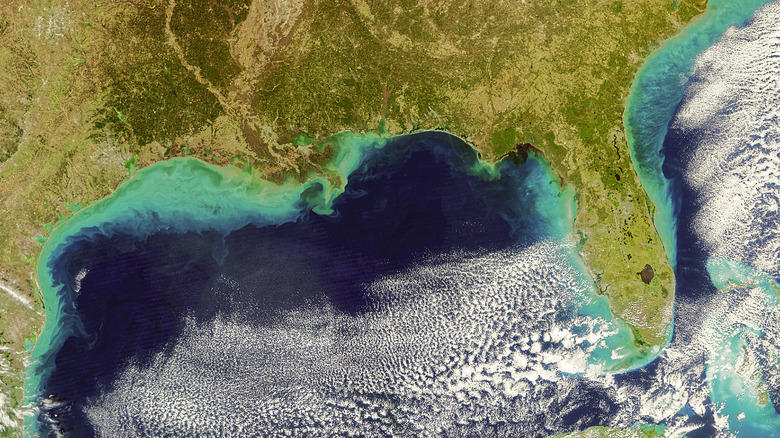

When taken together, these three missions provide data on ocean salinity on a global level stretching back for a full decade. The researchers were particularly interested in coastal waters, which are the parts of the ocean closest to land. These are not only most important to humans, given how concentrated settlements are to coastlines, but are also thought to be regions where changes to the planet's water cycle would be seen most.

The research found that the ocean salinity in these coastal waters peaked in March and fell to its lowest in September, following a regular yearly pattern. That's different from the rest of the ocean, open waters, where it peaks in February to April and drops in July to October. The effects were bigger in the coastal waters than on the open ocean, and the yearly variations in salinity at the coastlines were strongly correlated with the El Niño system.

"Given the sensitivity to rainfall and runoff, coastal salinity could serve as a kind of bellwether, indicating other changes unfolding in the water cycle," Fournier said.