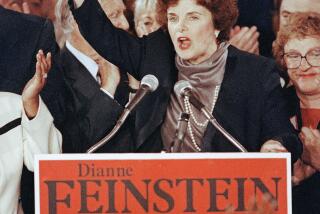

Delaine Eastin, pioneering California politician, dies at 76

Delaine Eastin, a trailblazer who is among a handful of women ever elected to statewide office in California, has died after suffering a stroke, according to her representatives. She was 76.

“Delaine will be remembered for her boundless intellect, infinitely compassionate spirit, sharp sense of humor, and courageous leadership in local, state, national and international realms,” said a statement released by those close to Eastin after her death on April 23. “Her love of education, children, animals, gardens, and the arts shined through everything that she did.”

The first and only woman elected state superintendent of public schools, Eastin and her then-husband were unable to have children. After she won the post in 1994, Eastin recalled that he told her, “Now you have 6.1 million children.”

This ethos was rooted in Eastin’s core beliefs. She grew up in a blue-collar family that stressed the importance of education. Her father, a machinist originally from Appalachia, gave her $1 for every poem she memorized, put a second mortgage on the family home to pay her college costs and wept at her graduation.

“Education changed my life forever,” Eastin told The Times in 2018 during her bid for California governor. “I want that for every kid.”

Delaine Eastin was a sophomore in high school when a drama teacher urged her to try out for a part in “The Man Who Came to Dinner.”

Born in 1947 in San Diego, Eastin grew up primarily in San Carlos. Though neither her father nor mother, a store clerk from San Francisco, attended college, both prioritized the importance of school.

“My dad said education gives you choices,” Eastin recalled in 2018. “He felt like he didn’t always have choices.”

Educators were pivotal to shaping her future, she added, notably a Carlmont High School drama teacher who urged her to try out for a part in “The Man Who Came to Dinner.” When she balked, he told her, “This is a metaphor for your whole life. If you never try out, you will never get the part.”

After winning the role, Eastin said that advice stuck with her.

She earned a bachelor’s degree from UC Davis in 1969 and a master’s from UC Santa Barbara in 1971, both in political science, and then taught at community colleges and worked in the private sector before running for office. Eastin was elected to the Union City City Council in 1980 and then represented parts of Alameda and Santa Clara counties in the state Legislature from 1986 to 1992.

She was one of only a few female state lawmakers at the time.

“Women were especially close to each other in those days,” Eastin told the Orange County Register in 2023. “Women did look after one another because we sort of had to, because we would be dismissed or spoken down to in some instances unless we stood up for each other.”

“I remember in the early days, there were people who wouldn’t let me on the members’ elevator because I was a girl, and I couldn’t possibly be a member,” Eastin recalled, noting that at one point, an Assembly leader referred to the legislative women’s caucus as the “Lipstick Caucus.” He ultimately apologized.

Eastin’s then-colleagues remembered her as a mentor.

“Boy was I lucky! In 1990, I was a brand-new assemblywoman and Delaine took me under her wing,” said former state Sen. DeDe Alpert, who served in the state Assembly with Eastin. “Her knowledge and leadership skills helped me with policy issues and politics. At a time when there weren’t many women in the Legislature, she was a wonderful leader who made it her job to bring along the newer women members. She was so generous with her time and talent.”

Eastin was then elected superintendent of public instruction, serving from 1995 through 2003.

“Her dedication and foresight to nurturing and preparing students for the future laid the foundation for what has been possible for our students today,” Tony Thurmond, the current superintendent of public instruction, wrote on social media, noting Eastin’s focus on universal preschool, nutrition and celebrating educators.

Visit: State schools chief tours local campuses and delivers well-received speech calling on community leaders to do more to help students.

Eastin unsuccessfully ran for governor in 2018. While she lacked the necessary fundraising ability and statewide name recognition to win the seat, Eastin won the admiration of her Democratic rivals and party activists.

They lauded her history, beliefs and wit, such as when she was asked about student testing during a gubernatorial debate and replied, “You don’t fatten a hog by weighing it more often.”

Eastin is survived by two women whom she considered her “chosen daughters,” Daisy Gonzales, a former foster child who is the deputy chancellor of the state’s community college system, and Maha Ibrahim, a lawyer with Equal Rights Advocates.

“Delaine taught us that leadership is about values and empowering the next generation to find their voice. Education was the tool to ignite change,” Gonzales said.

“Delaine also taught me that family could look many different ways,” she added. “She had complete trust and love for future generations, and was unafraid of what is different or new. She was a trailblazer, a hero, and a mentor to many. To Maha and me, she was also family.”

Eastin is also survived by cousins, nieces and nephews. A celebration of her life is expected to be held this summer in Davis.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.