In the rapidly gentrifying Mexico City neighborhood of Juarez, tourists roll suitcases to luxury Airbnbs, and music bumps from pool parties at Soho House, a new members-only club. Shops sell designer underwear. Cafes serve caviar.

And then there are the tents — hundreds of them — that fill the streets.

Here, destitute migrants from around the world bide time as they wait for the opportunity to request asylum at the U.S. border. Entire families from Haiti, Venezuela and other places in upheaval live exposed to the elements, cooking over open fires, bathing in water pilfered from fountains and finding ways to relieve themselves without public restrooms.

Despite the hardships, Karenis Álvarez, 36, said the three months she has spent camped here haven’t been worse than life back in Venezuela, where food and electricity are scarce, and the education and health systems have collapsed.

“We have a place to sleep,” said Álvarez. “Even if it’s a tent.”

The sprawling encampment has triggered protests from angry neighbors, who chanted, “The street is not a shelter!” during a recent demonstration, as organizers complained to local journalists that the migrants were making the area unsafe. It has also sparked outcry from humanitarian organizations that implore Mexico to do more to protect the people traversing its territory.

Above all, it has become a symbol of how an uptick in global migration is transforming not just the United States border but nations to its south.

In Costa Rica, migrants — mostly from Nicaragua — make up 10% of the population.

In Panama, humanitarian networks have been so overwhelmed by the hundreds of thousands of migrants on the march that authorities have started moving them north in buses.

And in Colombia, nearly 3 million Venezuelans have sought refuge in recent years; 2 million others have landed in Ecuador and Peru.

The pressures are also acute in Mexico, where a series of U.S. policies in recent years have forced many migrants to wait for extended periods, and where leaders are under pressure from their American counterparts to keep migrants away from the border.

Mexican authorities have stepped up their enforcement in the north of the country — setting up an extensive net of checkpoints and deporting migrants back to their home countries or sending them south on buses. Many migrants say Mexico City, where enforcement actions are less common, feels safer. But with some shelters here crowded to four times their capacity, migrants have had to improvise, erecting tents in various parts of the metropolis, including Juarez.

Known for its leafy streets and historic architecture, the neighborhood has changed rapidly in recent years, with rents soaring and high-brow restaurants and Pilates studios moving in.

Like other parts of Mexico City, Juarez has become a hub for tourists and “digital nomads” — remote workers, many from the United States, who move abroad in part to take advantage of the lower cost of living. They crowd natural wine bars, browse high-end clothing shops and cruise around on bicycle “taco tours.”

American tourists and remote workers are gentrifying some of Mexico City’s most treasured neighborhoods. Backlash is growing.

Then there are foreigners like Keyla Arriaga.

On a recent hot afternoon, the 23-year-old sat on a dusty couch in the middle of a street. As a dog walker steered his pack around tents and a pair of sunburned travelers walked by sipping beers, Arriaga nursed her infant daughter with one hand and navigated a U.S. government smartphone app with the other.

The app, CBP One, would allow Arriaga to schedule an appointment at a U.S. port of entry, where she could request asylum for herself, her baby and her two young sons, who were tugging at her, increasingly impatient.

“Mami, I’m thirsty,” said Bryan, 5.

“Mami, I want to play,” said Dylan, 7.

Arriaga shushed them as she rifled through a stack of crumpled birth certificates and other identity documents in search of information the app required.

They had fled their hometown of Guayaquil, Ecuador, to escape rapidly escalating gang violence. Arriaga hoped to get out of Mexico as soon as possible, given what she had heard about the country’s cartels and the propensity of authorities to extort from migrants.

“The longer I’m here, the more bad things can happen to me,” she said.

But like many in this camp, she is stranded. Migrants can’t access CBP One south of Mexico City, and in the north, the threat of deportation looms. And once they apply, the wait for an appointment can last months.

Many migrants try to find jobs in the meantime.

In the main market in Juarez, a noisy labyrinth of stalls where vendors sell food, plants and clothing, it’s not uncommon to hear Haitian Creole mixed in with Spanish and with English from tourists.

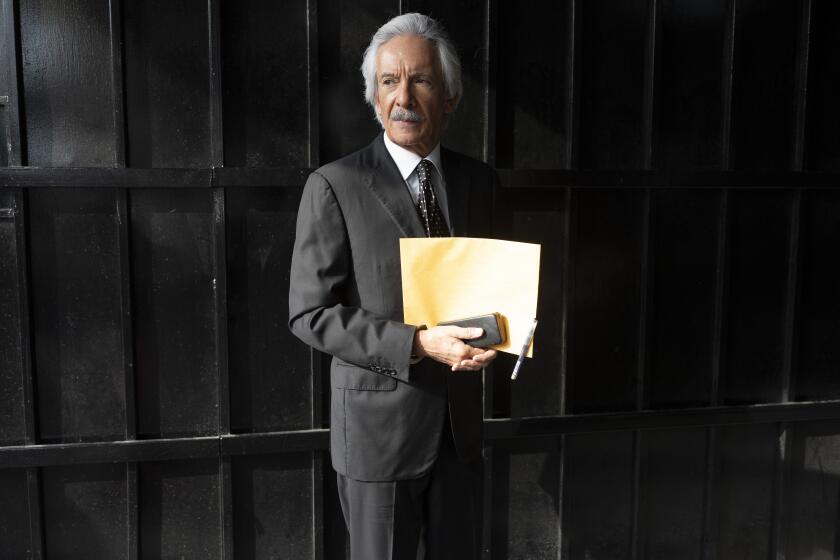

Marc Arthur Garcon, 52, is one of two Haitians who works for a butcher. Back home, he owned a photo studio. But after the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moise plunged Haiti into turmoil, he sold his car and bought a one-way plane ticket to Nicaragua.

When he arrived in Mexico, he applied for asylum, thinking he might like to live here in the long term.

Asylum claims in Mexico have increased more than a hundredfold over the last decade, from 1,300 applications in 2013 to 141,000 last year.

In the end, Garcon decided against staying in Mexico, given how little he earns making deliveries on bicycle — $16 for each 12-hour shift. He’s also concerned about the growing ire from neighbors. But he knows, too, that the U.S. is not a sure bet, and he could face deportation once he enters. He feels sometimes like there is simply no place for him.

“I’m really frustrated,” he said.

The encampment has been a frequent topic of conversation for longtime residents of Juarez such as Idelbrano López, 40.

Seeing kids living on the street makes him sad, he said. And the unsanitary conditions of the camp make him worried for his own family.

“As a human being, I want to help them, but if we keep helping them, they might stay forever,” he said.

Others in the neighborhood said worries about the migrants are a distraction from the issue of gentrification.

“They don’t give us any problems,” said Lorena Perez, 50. “The real problem here is the rising costs.”

Isaac Contreras, a local volunteer who comes to the encampment daily to teach art to the children living there, recently organized a party for the migrants. A restaurant donated food and cake. Children sang songs in Creole. Some of the adults danced.

Contreras said it’s important that he and others in the community get to know the people living on their doorstep.

“We’re neighbors,” Contreras said. “How are we going to create a community together?”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.