Six Science Fiction Devices That Became Real

It takes a dreamer to think outside the box, imagine something impossible, and conjure up uses for an object previously undreamt. Artists and authors have created unbelievable situations in their works for as long as art has existed. Technologists and scientists have only recently become possible to pluck something from fiction and build it for use in the real world.

The Scientific Revolution was a powerful reminder that we could unlock incredible discoveries by analyzing empirical results, followed by rigorous testing and studying. The Industrial Revolution demonstrated how standardized production could revolutionize our world, creating high-quality, precise instruments on a mass scale. The fevered imagination of the artist has always been a catalyst, opening our eyes to possibilities we never even knew existed.

Believed once to be relegated to the sphere of thought experiments, science fiction technology has sprung into reality through the tireless efforts of dreamers, engineers, scientists, and academics. Check out our guide to six science fiction devices that became real.

Babel fish translator

While a brainwave-powered real-time translator that fits in your ear may still be a thing of the future, handheld translating technologies have made enormous strides in helping travelers navigate foreign places.

In Douglas Adams's classic "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," protagonist Arthur Dent travels across the cosmos. Though fantastical in scope, Dent's adventure presents a relatively mundane problem first, one faced by millions of travelers each year — understanding the languages of the places you are going. In this sci-fi novel, Dent receives a small yellow fish known as a Babel fish, which instantly translates everything into Dent's language so that he hears it as a native speaker.

Travelers may not yet have access to real-time translation beamed directly into their neurons, but the rise of the smartphone has completely changed the translation space. Ubiquitous access to computer processing and the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has given travelers photo-based translation. Google Translate and iTranslate require a glance at a foreign language with a phone camera to detect and translate right on the screen. These apps are not flawless, but they help if you find yourself in a crowded supermarket in Seoul or lost in the canals of Venice.

Real-time live translation is becoming a thing of the present. Companies like Kyocera and Timekettle alongside big technology firms like Google and Apple are implementing pre-trained AI to turn live speech into translated captions or dialogue in real-time. It's not quite the direct-to-the-brain integration of the Babel fish, but at least this way, you don't have to put a fish in your ear.

Orbital launch vehicle

There is some discussion regarding what qualifies as the earliest form of science fiction. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein has been mentioned as the genesis of modern sci-fi upon its release in 1818, while others say the 1638 novel "The Man in the Moone," in which an explorer builds a spaceship and meets extraterrestrials is a better example.

Born in France in 1828, just in time for the height of the Industrial Revolution, Jules Verne grew up spurning his father's desire that he be an attorney. He turned to literature. While working at the Paris Stock Market, Verne wrote at night, envisioning a new novel genre that mixed adventure with scientific fact. Prolific in his time, many of Verne's fantastical creations came true, including a moonshot.

In 1865, Verne released "From the Earth to the Moon," a novel exploring the adventures of the Baltimore Gun Club as they seek to build a massive cannon and blast a bullet to the moon. In the story, Verne calculates the force it would take to reach the moon (via a 274-meter deep hole in the earth filled with 122 metric tons of gun cotton), determines an ideal launch location in Florida, and devises a bullet-shaped rocket to carry a crew of three. Verne even predicted the cost of such an endeavor ($5,446,675, or about $12 billion in 1969), the construction material of the projectile (aluminum), and the weight (19,250 pounds empty, while the Apollo 8 spacecraft weighed 26,275 pounds).

Bionic limbs

Luke Skywalker losing his hand to Darth Vader at the end of the Empire Strikes Back has an emotional weight for sci-fi fans of a certain age. But we needn't have feared – he soon has a fully functional replacement.

As it turns out, that scene inspired the "LUKE Arm" developed by the University of Utah. Jacob George, director of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, helped create the bionic appendage with silicon skin, a sense of touch for the user, and the ability to manipulate the prosthetic simply by thinking. The prosthetic sends signals to the brain indicating how hard or soft one should hold an object -– something impossible with body-powered hooks and other prosthetics.

This prosthetic arm and others of its ilk remain prohibitively expensive and limited in availability for the average amputee. However, the upside of the cost coming down as technology and processes improve is nearly limitless, drawing closer to a gap in ability that has hindered amputees for centuries. Once upon a time, limb loss accounted for a carved wooden replacement or a crude device for manipulating objects. However, the imaginations of sci-fi writers and practical applications of academic scientists may be bringing those days to a close.

Cloning

In the past 30 years, the concept of cloning has gone from being heard only in a science fiction context to being part of a reasonable discourse. Millennials will remember Dolly the Sheep — a cloned bit of livestock that forced humanity to review deep moral questions.

The concept of cloning, a topic that has long fascinated science fiction writers, was introduced as early as Aldous Huxley's 1932 novel "Brave New World." In this novel, Huxley presents Bokanovsky's Process, a form of in-vitro fertilization that can generate up to 96 identical copies of an individual. The idea of cloning, with its profound moral and ethical implications, became a reality that humans had to confront directly in the early 1990s.

Dolly was born on July 5, 1996, but she did not come into this world via another sheep. Dolly began developing as a mammary cell containing all the information needed to create a sheep. She was the first adult mammal cloned, proving the previous theory that adult cloning was impossible. Dolly resulted from a process later known as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Cloning humans is severely frowned upon and is outlawed by several organizations.

Not to worry. SCNT had limited results with primates. Besides, who would want to clone a few Thomas Jeffersons, raise them under different circumstances, and see how they turn out? No one, and whoever conceived of that possibility, must be a madman. Cloning today is considered a high-risk, low-reward activity.

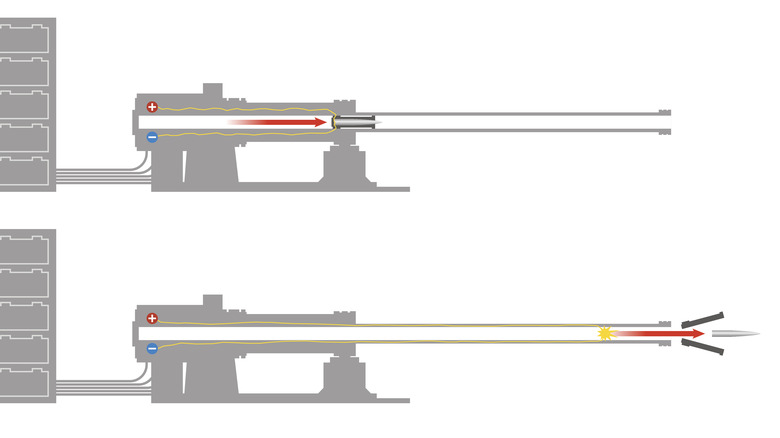

Rail guns

From the arms of mega-mechs to the decks of battleships, rail guns have moved from science fiction into real life, though they may soon return to the pages of fantasy. Science fiction technologies often use magnet-powered devices. Maglev trains have proven the power of magnets to hurl train cars at enormous speeds, so why not lethal projectiles? Electromagnetic rail guns do just that.

In John Munro's 1897 story "A Trip to Venus," the author imagines electrically powered guns slinging craft into space. In 1918, French engineer Louis Octave Fauchon-Villeplee generated the first design of the rail gun. Though never built, it inspired the German Flak Command to investigate the possibility of an anti-aircraft rail gun, which was also never built during the Second World War. Advancing American troops discovered the plans and grew interested in the concept.

Rail guns have potential benefits: improved range, simple ammunition construction and maintenance, and faster projectile speeds. Unfortunately, it also requires an enormous well of electrical power to achieve these benefits. The U.S. Navy tried to build rail guns that could launch projectiles at seven times the speed of sound for their Zumwalt-class destroyers. The Zumwalt and the rail gun project are dead, though Japan has proposed teaming up with the United States to develop a rail gun to defend against hypersonic missile attacks. Could the century-old concept have a place in the future?

Land ironclads (Tanks)

H.G. Wells stands tall in the pantheon of science fiction writers. Unsurprisingly, the man who developed the source content for the "War of the Worlds" broadcast in 1938 had his finger on the pulse of future technologies when he imagined battle tanks nearly 15 years before their invention.

Ironclad ships had been cruising the seas since the end of the American Civil War in 1865. The mechanical beasts seemed impervious to enemy fire while bringing devastating firepower all their own. Though the Great War would not break out for another 11 years after the story's publication, Well's modified vision leaped into existence.

In the 1903 story, Wells imagines a bleak battlefield crisscrossed with trenches and stuck in the throes of a stalemate. The arrival of a dozen or more "land ironclads," tread-driven and armored vehicles 80 to 100 feet long, broke the deadlock. Engineers would run the machine while soldiers used their gunports to advance. Ultimately, poorly trained but mechanically superior soldiers overrun their armorless enemy. Though the early tanks of the World War I differed enormously from what Wells put forth, the idea of armored battle tanks has stretched deep into the next century.