The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for it

The chromosome loss is linked to cancer and Alzheimer's

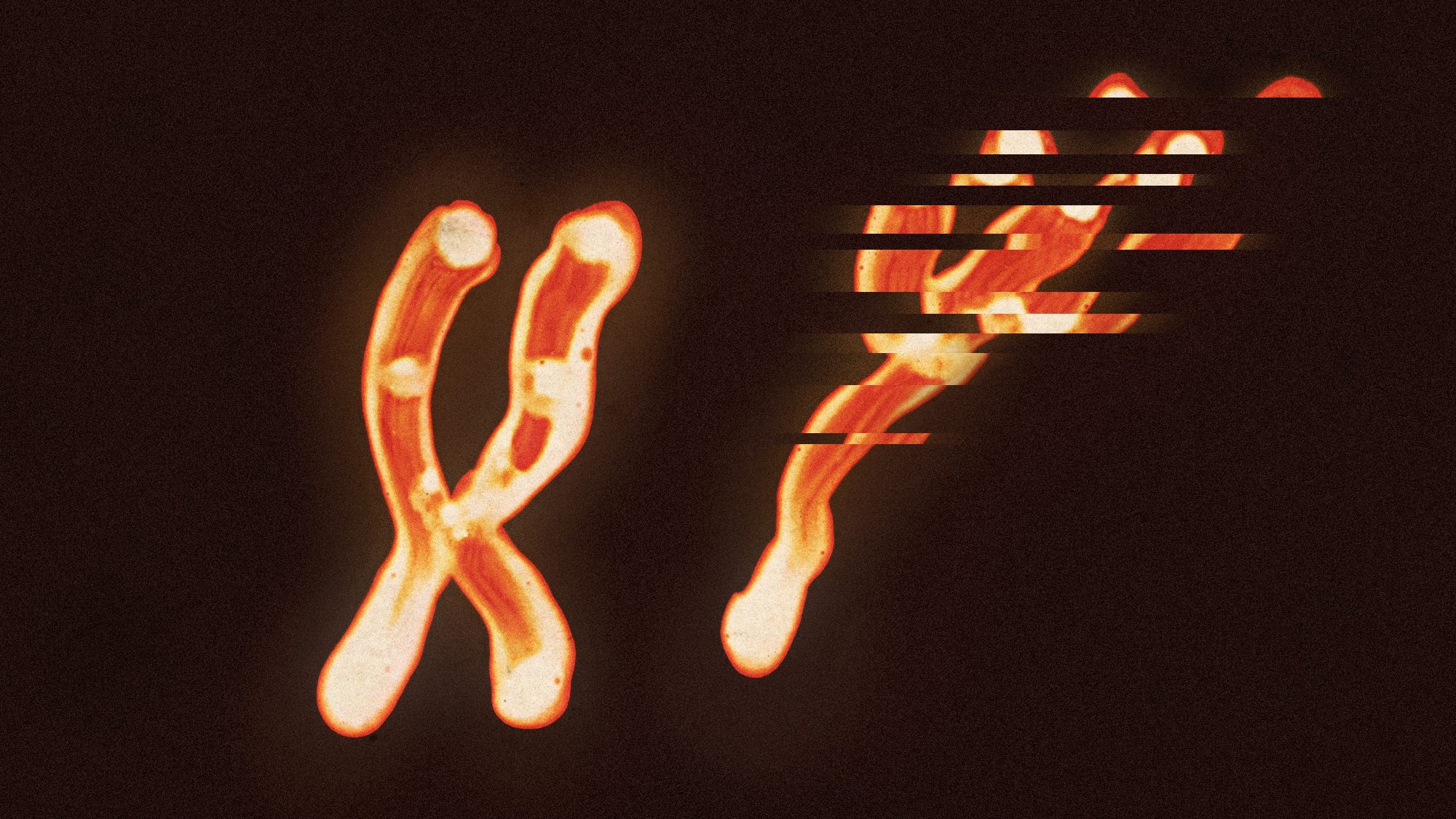

The Y chromosome can disappear over time in human males, which may introduce a number of health problems. While the exact trigger for such degeneration is unknown, environmental factors can play a significant role. New research on the topic hints that the human Y chromosome is evolutionarily unstable and could even become extinct.

Chromosomal complications

Most people have 23 pairs of chromosomes, including a pair of sex chromosomes that can be either an X chromosome or a Y chromosome. Having two X chromosomes usually designates a human as biologically female, while having one X chromosome and one Y chromosome designates a human as male, though this is separate from a person's gender identity.

The Y chromosome is about one-third the size of the X and contains far fewer genes. Now, scientists have found that this smaller chromosome can degrade over time. "The idea is that as men grow older, they lose this chromosome from many of their cells, which drives age-related disease," said New Scientist.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) has "important effects in shaping the activity of the immune system," and can open the door wider for several diseases, including "cancer, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and acute infection," said a January 2025 study published in the journal Nature Reviews Genetics. "If you're a male, you do not want to lose your Y chromosome, it's definitely going to shorten your life," Kenneth Walsh, a professor at the University of Virginia, said to New Scientist.

When it comes to cancer, "tumors without the Y chromosome grew twice as fast as those with it," said New Scientist. This is largely because the "loss of the Y chromosome causes tumor cells to make proteins that exhaust T cells, a kind of immune cell that ordinarily recognizes and attacks cancers." In addition, research has shown that the risk of Alzheimer's disease greatly increases with LOY. Experts speculate that the "Y chromosome-deficient immune cells infiltrate the brain and may lead to increased inflammation or may be less able to regulate the inflammatory response," a symptom which is "characteristic of Alzheimer's disease," the study said.

Micro mistakes

Y chromosome loss is largely "due to cell division mistakes," said News Medical. This is "enormously common" and "not like some freakish accident," Lars Forsberg, a senior lecturer and associate professor at Uppsala University in Sweden, said to New Scientist. It likely happens to all males, but age increases the level of loss. Additionally, there is "no data to suggest that men with loss of Y would feel it."

Other contributing factors include smoking and exposure to environmental toxins like air pollution, glyphosate herbicides and arsenic-contaminated water. Quitting smoking could reduce the risk, and "future research may identify specific mutations or factors that trigger LOY," said News Medical.

LOY is "increasingly viewed as a marker of genome instability and a biological indicator of environmental stress," said News Medical. It could also be a major reason why females tend to have longer lifespans. "Females seem to be the stronger sex from a genetic point of view, with a more stable and less disease-prone genome," said the study. While the Y chromosome degrades on the individual level, there is evidence that the chromosome may be going extinct on an evolutionary scale.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Flying into danger

Flying into dangerFeature America's air traffic control system is in crisis. Can it be fixed?

-

Pocket change: The demise of the penny

Pocket change: The demise of the pennyFeature The penny is being phased out as the Treasury plans to halt production by 2026

-

Time's up: The Democratic gerontocracy

Time's up: The Democratic gerontocracyFeature The Democratic party is losing key seats as they refuse to retire aging leaders

-

The New World screwworm is making a deadly comeback

The New World screwworm is making a deadly comebackThe explainer The parasite is spreading quickly

-

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatine

'Wonder drug': the potential health benefits of creatineThe Explainer Popular fitness supplement shows promise in easing symptoms of everything from depression to menopause and could even help prevent Alzheimer's

-

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kids

RFK Jr. scraps Covid shots for pregnant women, kidsSpeed Read The Health Secretary announced a policy change without informing CDC officials

-

Women need more pain management during gynecological procedures

Women need more pain management during gynecological proceduresUnder the radar Pain should no longer be ignored

-

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sick

New FDA chiefs limit Covid-19 shots to elderly, sickspeed read The FDA set stricter approval standards for booster shots

-

A tick-borne illness is making its rounds in new parts of America

A tick-borne illness is making its rounds in new parts of AmericaUnder the radar Babesiosis, spread through blacklegged or deer tick bites, is a growing risk

-

US overdose deaths plunged 27% last year

US overdose deaths plunged 27% last yearspeed read Drug overdose still 'remains the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18-44,' said the CDC

-

Trump seeks to cut drug prices via executive order

Trump seeks to cut drug prices via executive orderspeed read The president's order tells pharmaceutical companies to lower prescription drug prices, but it will likely be thrown out by the courts