From the Archives: A few weeks in paradise for 1984 urban nomads

On Feb. 5, 1984, staff photographer Ken Lubas spent the day with a small group of Native Americans living in makeshift shelters on Bunker Hill. By Feb. 12, 1984 — when a Los Angeles Times story appeared on the homeless group — they had been evicted.

Staff writer Jerry Cohen reported:

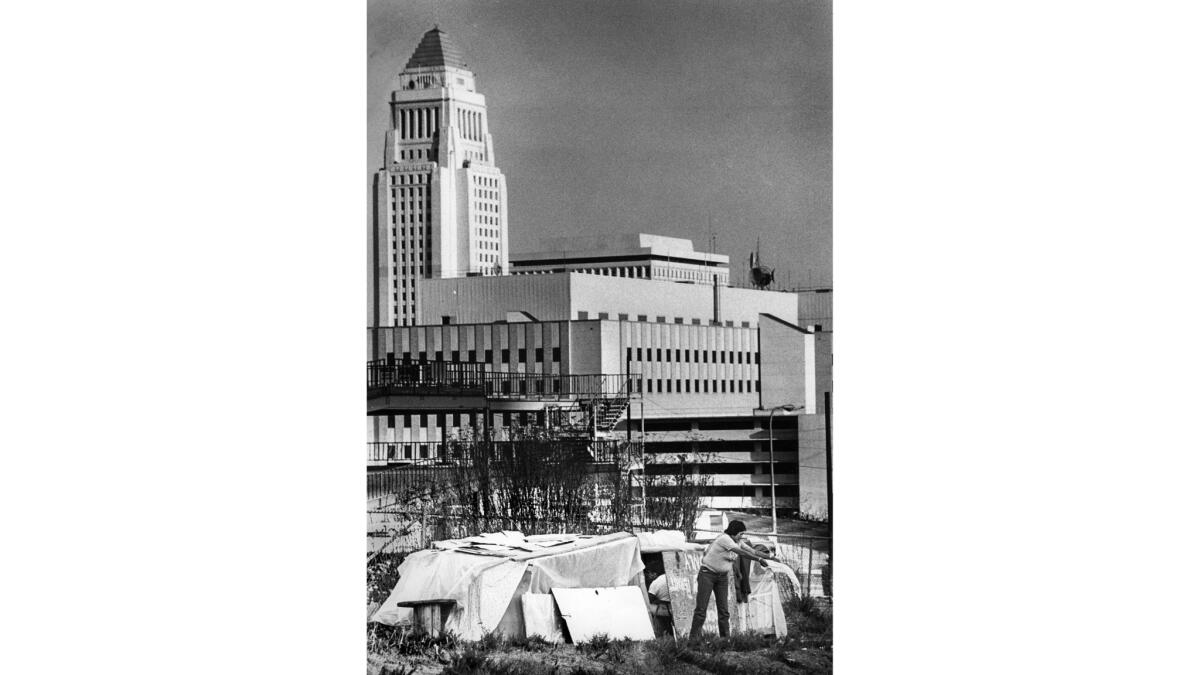

Of all the homeless men and women who grub for nighttime shelter either below droning freeways, in boozy doorways or simply under the open sky, none could claim the creature comforts found in three elaborate huts planted on a vacant lot halfway up Bunker Hill.

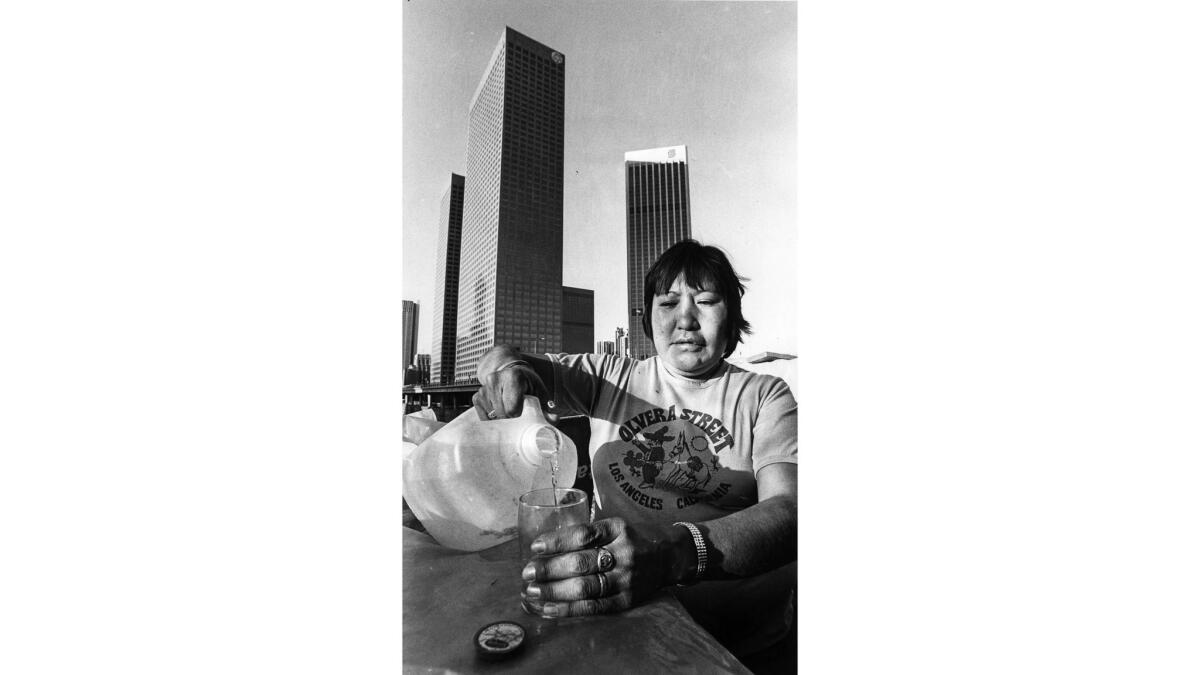

For the little band of urban nomads struggling to survive there beneath a spiky jungle of new skyscrapers and a mere shout away from Los Angeles’ imposing Civic and Music centers, the arrangement its members had contrived was as comforting as it was cozy.

Until just the other day.

Now the “cardboard condos,” as passers-by had called them, are vacant. And the four American Indians who built and occupied them must look elsewhere for less hospitable places to sleep when night falls.

Nobody is to blame for the forced decampment. Police officers did what the law dictates they must when they ordered the quartet to leave because the Indians were trespassing on city property.

But the four had a good thing going while it lasted — three full weeks of it. And to call their erstwhile dwellings “cardboard condos’” is hardly fair. The little colony of vagabonds lovingly constructed the huts’ plywood overlaid with plastic sheeting to hold back the rain. A more accurate description might be wooden hogans.

“It was really comfortable. I called it my ‘reservation,’ ” said Wilma Aros, 32, the youngest of the band and the only female among the four. “When it rained, we had that plastic over our heads and we never got wet at all.”

Until the huts were completed three weeks ago, Aros, a Jicarilla Apache who was born and spent her early years on a reservation in Colorado, had been sleeping outdoors for the last two years, mostly in a county parking structure adjacent to the vacant lot bounded by the open-air building and Gen. Thaddeus Kosciuszko Way and Olive Street and Grand Avenue, land owned by the Community Redevelopment Agency.

“Now I don’t know what we’re gonna go,” she said.

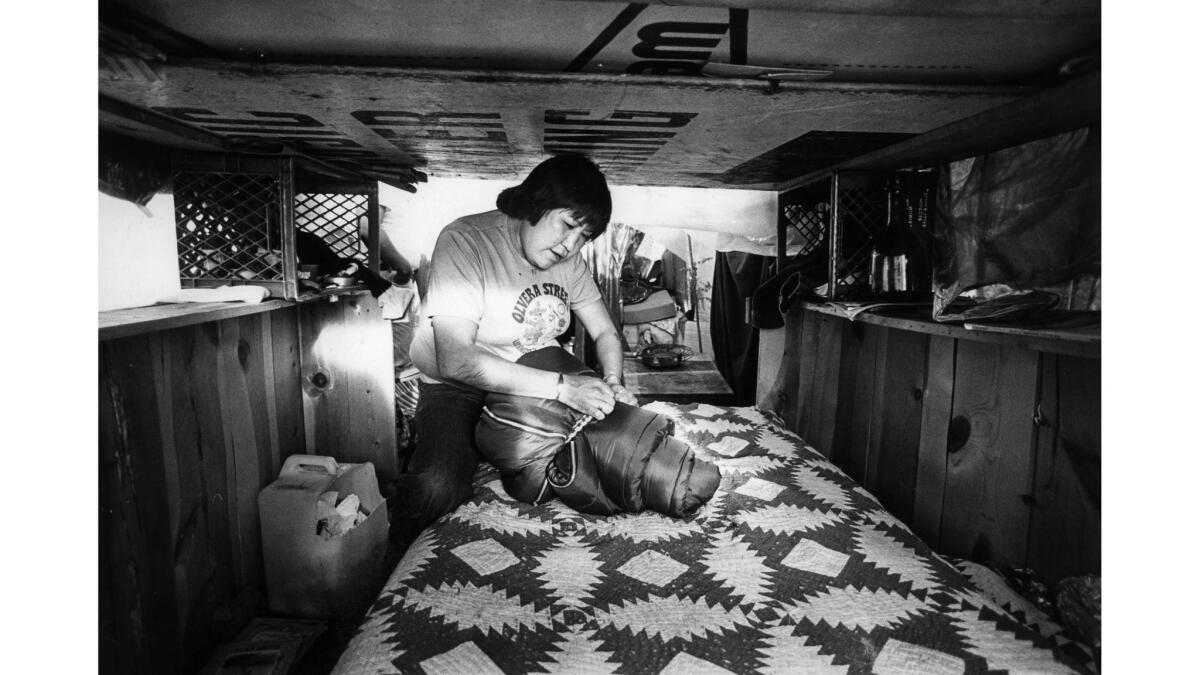

What she and the male companion she lived with left behind actually was a mere shanty, sort of an 8-foot-by-8-foot plywood hogan built around a mattress, elevated on wooden blocks, and not much else. Hardly palatial. But by street people’s standards an incomparable comfortable nest.

A hut to the west of it was of similar size, a white one to the east was the least of the three, really nothing more than a frame around a tattered final couch — but still luxurious when compared to the bare cardboard on which the four had been sleeping for months in the parking structure. “We were robbed there so many times I can’t even remember. They took every little thing we got. Our ID cards, our Social Security cards. Everything they could rob us of,” Aros said.

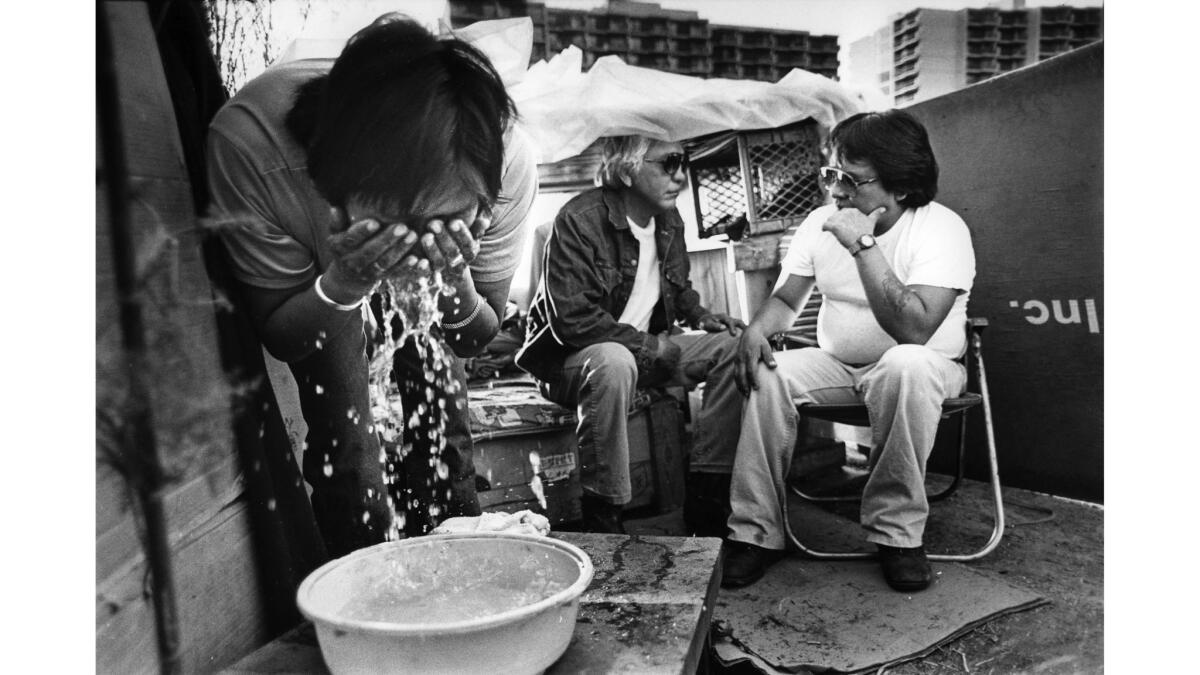

Chunky and jolly, Aros and her three male friends are not your commonplace unkempt street people. What sets them apart principally is their cleanliness. She, for example, showered daily at a skid row center for homeless women, and her companion, Jack Yazzie, 50, a Utah Navajo and also reservation-born, at the Midnight Mission. Each week they trekked to the nearest laundromat in Echo Park to do their washing. “We don’t want to get any lice,” Aros said.

They had furnished their huts with items retrieved from dumpsters — mattresses and bed clothing, a charcoal grill, chairs and a small table and large plastic bottles to hold their water supply.

Each morning, Aros carefully made her and Yazzie’s bed, topping it off with a gaily colored spread neatly tucked in.

The pair met about a year ago when Yazzie, before a disabling injury, still was able to find various odd jobs through a skid row labor pool. Aros credits Yazzie, a taciturn, but friendly man, with virtually saving her life by teaching her how to live in the hostile environment of big city poverty.

It was the custom of the four friends, before being ordered to abandon their hillside shelters, to rise early and set off for the United Indian Involvement Center on skid row, where they were given breakfast and later a mid-afternoon dinner. The four spend most of their daylight hours in and around the center. All are jobless.

They scraped together money for their weekly laundry by collecting aluminum cans and selling them for 30 cents a pound. “We make about five or 10 bucks a week that way,” Aros said.

After the story ran, there was no further mention of Wilma Aros in the Los Angeles Times archives.

This article was originally published on Dec. 9, 2016.

See more from the Los Angeles Times archives here

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.