Art starts with a drawing – specifically a drawing by a clever young girl named Kora, otherwise known as the Maid of Corinth. Kora is a teenager in ancient Greece who has fallen in love with a soldier. Alas he is called up to war. Desperate to keep hold of him, or some memory of his handsome presence, Kora asks him to stand against a wall in bright sunlight so she can draw the outline of his shadow. His trace remains, held there for ever by her perfect line. And thus drawing is born, at least according to Pliny.

It’s a tall story. We all know that drawing goes right back to the wild horses running across the caves of Lascaux, to the prehistoric riders of Bhimbetka and the magnificent bison of Altamira. There are drawings on ice-age animal skins and ancient Egyptian papyruses. But the story of Kora endures, partly because she has a name, but also because she is driven to drawing by love: you might say that the Maid of Corinth is, like many of us, a passionate amateur.

Drawing is democracy. Everyone does it. You doodle in the margins of this newspaper. I sketch the view while hanging on the phone. We draw on our hands, on walls, on the back of envelopes (like Monet), on office notepaper (like Van Gogh), on restaurant napkins (like Picasso and Warhol). We draw to pass the time, to catch the moment, to remind ourselves what we saw, felt or thought. We draw to see what life looks like in two dimensions. We draw because we can – and everyone can – and because we’re trying to improve. We draw to see what we can make of the world, or for the sheer joy of it; to show something to somebody else – here, this is what it looked like. We draw to make a map, with a couple of decorative trees; to see if our two-circle cat looks anything like the real thing; to play games with each other, show the police what we witnessed, send a message to someone else; to give each other something particular, something special, to say something that cannot otherwise be said. We all do it. And we do it from the first.

Drawing is the speech of art. The words we utter, the stories we tell. It comes before writing – tiny infants do it – and quite often after script has departed (my artist mother can scarcely write now, in her 90s, yet still she draws). Holding a stub of crayon or chalk comes early and late. All children scrawl and scribble at first, absorbed by their own power to leave marks on paper; then they may describe something seen in the world. The sun is a circle radiating ray lines, a flower the same but with loops, stick figures abound from Lascaux to the present day. Perhaps it is true, as the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget proposed, that children’s drawings have a universal quality. Certainly our brains are able to read two dots and a dash as a face from the earliest age, just as it is, for most of us, the configuration of our first drawn portrait.

But though we all draw, the belief persists that we cannot draw, that there is some correct way to do it beyond our talent or ken. Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Dürer – they were the masters, they showed us the heights to which we can’t hope to aspire. This defeatism still holds fast in some place, despite a century of ice-breaking modern art, and every kind of drawing from the mescaline-driven hallucinations of Henri Michaux to the fine lines of an Agnes Martin grid. Picasso’s famous remark, adapted – that it took him only four years to draw like Raphael, but a lifetime to draw like a child – used to be everywhere quoted as a call to break free of academic tradition: no more drawing from plaster casts of Roman sculptures. But his epigram fell out of fashion at roughly the same time as the teaching of drawing itself, somewhere in the mid-1980s.

This great art – that makes ideas visible on paper, that shows the mind and hand working together, and all at once – was gradually required less and less often in schools and colleges. Conceptual art, performance art, installation, video, film and digital art: they all made drawing (supposedly) redundant. By the 1990s, life classes were fading out of art schools everywhere and Goldsmiths notoriously banned the practice, in case it objectified the female model. You can’t draw and yet you call yourself an artist: the old jibe, turned on its head, became a statement of fact for many contemporary practitioners (not coincidentally, the arid technocratic term that took hold around that time). Except that this is not how it was for anyone who loved to draw, to look at drawings, to attend evening classes, even just to get down on paper the sights of our lives, or our minds, however crudely – that is to say, the rest of the world.

Of all the many privileges of my job as art critic for this newspaper, not least is the chance to see drawings everywhere – in public exhibitions and private studios, the image sometimes arriving there and then on the page (as performed by Paula Rego and Ken Kiff, who started every morning with drawings). In desiccated old folios where the dust dances on the page as you examine Gainsborough’s 10-second sketch of his daughter laughing. In the vaults of the Louvre, where the white-gloved handler had to turn away from a sketch of a disillusioned actor by Daumier to stifle the sneeze that might have blown the chalk away.

I can’t paint to any standard, but my inner draughtsman instinctively traces all these drawings. This must surely be a common primal urge, a way of entering an image (and the world) more completely. As a child, my favourite book was Catherine Storr’s Marianne Dreams, in which a bedridden girl makes drawings with the stub of a pencil to pass the time – a garden, a house, a figure at the window – only to discover that she can move about inside this house at night in her dreams, and then alter the narrative of those dreams by day as she draws and redraws her pictures. This, for me, was the true power of drawing.

And now this art has come stealthily back to the front of the stage. If you’ve been keeping your eyes open, you will have noticed the rise of drawing shows in recent years. Not just the masters – Michelangelo at the Royal Academy, Raphael at the Ashmolean, Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing, currently on at 12 different venues across Britain, and culminating in an all-together-now show at the Queen’s Gallery, London, in May – but the drawings of Monet and Degas, of Klimt and Schiele and Jackson Pollock, on to Agnes Martin, Bridget Riley and Rachel Whiteread. Whiteread’s drawings seem to me far superior to her sculptures. When I was a baby critic, a veteran colleague once told me to avoid drawing shows at all costs, since they were just preliminary exercises. But some of the greatest shows I have ever seen were composed entirely of graphic masterworks: Goya’s Black Border album, the drawings of Watteau, Botticelli’s astonishing illustrations for Dante’s Inferno, in which hell drills down like a tornado beneath the Earth’s crust: tiers of theatrical balconies from which tiny figures topple, descending to an everlasting winter – simply an icy-blue line, a circle from which no soul can ever return.

Drawing was always cool, always close, immediate, contemporary. Now drawing has returned to art colleges up and down the country. Every year, the Royal Drawing School receives hundreds of applications for its unique Drawing Year course, which allows postgraduate students to draw night and day, for free, and with the constant support of tutors who also teach public classes in still life, interior, draped figure, and life drawing in ink, charcoal and even iPad.

Collections of drawings are assembled by public museums but also private collectors. The latter often give to the former. Dürer’s drawings – including the incomparable hare, quivering with life in every line – are part of a magnificent collection founded by Duke Albert of Saxen-Teschen in 1776 that now includes a million masterpieces on paper. These are loaned to lucky galleries around the world by Vienna’s Albertina Museum, just as our British Museum sends its great drawing collection out into the world. The late Milanese jeweller Pino Rabolini, following the duke’s example in the 1960s, put together a body of drawings from De Chirico and Morandi through to arte povera and beyond that is nothing less than a survey of Italian art through the 20th century. It includes marvels made with pinpricks, DayGlo markers, wax crayons, Rotring pens and even iron compounds (back to Lascaux). You can see a selection now at London’s Estorick Collection.

And this spring, the very first art fair dedicated entirely to modern and contemporary drawings opens at the Saatchi Gallery in London. Draw Art Fair will showcase images by Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, alongside European masters from Jean Dubuffet to Francis Picabia. The fair’s founder, Laurent Boudier, who also started Le salon du dessin contemporain in Paris, likes to quote from that impeccable genius, Ingres, god to generations of draughtsmen from Degas to Hockney, on the essence of drawing. “To draw does not simply mean to reproduce contours; drawing is also expression, the inner content…Drawing is the probity of art.”

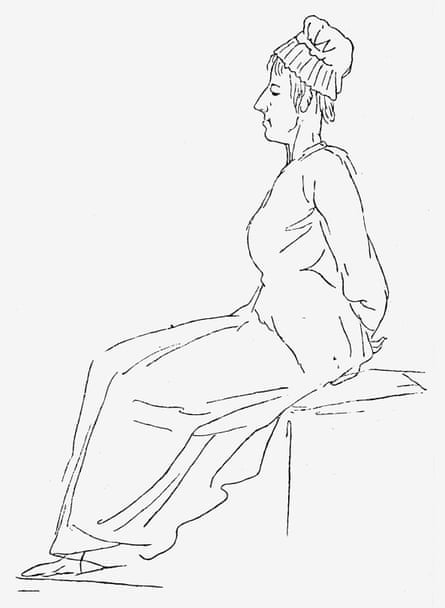

As a young man in Rome, Ingres summarised the faces of English expats in a pencil line so lithe and concise he could make enough money to support his new family in a few quick sittings a day. Drawings are made to be sold, like paintings, but perhaps for many more reasons. Dürer drew himself naked, pointing to the spot on his side where it hurt, specifically for a doctor to diagnose his condition. Schiele drew himself, repeatedly, in a prison cell to record each day of his confinement. He also drew his friend and mentor Gustav Klimt as a corpse in the morgue, commemorating Klimt’s handsome face in death, as if unable to say goodbye.

Louise Bourgeois drew to relax. Her Insomnia Drawings, of gorgeous blue rivers flowing among scarlet mountains, were made to achieve peace in the sleepless dark hours. Michaux drew his drug-induced hallucinations for release, transmitting the unpredictable shivers straight on to the page in ink. Goya drew what he witnessed, to record the terrible horrors of war; “I saw this”, he writes upon the pages of the Black Border album.

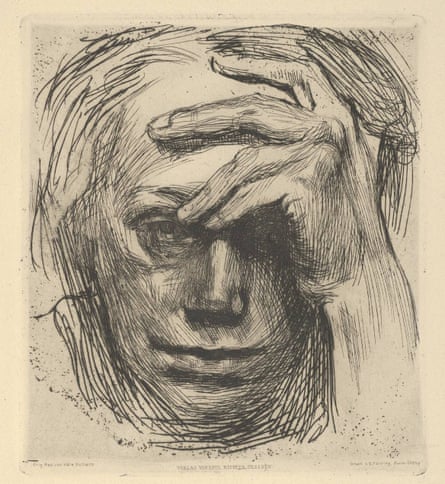

There is drawing for survival, in the devastating self-portraits of the great German artist Käthe Kollwitz – head in hand, in mourning, hunger, poverty and war. And drawing in old age – Degas, nearly blind in his 80s, did almost nothing but draw. At 80, the Japanese master Hokusai was once found weeping at his workbench because he had not yet learned enough about drawing. Three years later he drew himself with one hand raised high like a signpost, jaunty finger pointing ever onwards. It is known as Old Man Mad About Drawing.

Drawing catches the historic moment before, and after, the advent of photography. A sketch made only inches from Charles I during his trial before parliament shows the king exhausted and irritable, yet unbowed before his fate. David, in revolutionary Paris, drew Marie-Antoinette on her way to the guillotine, teeth gone, mouth sunken and hair chopped to nothing beneath a mob cap. There is humanity as well as shock in the drawing, and perhaps the medium is made for it, the mind transmitting its first observations and feelings directly to the hand.

Henry Moore, official artist of the second world war, drew sleepers sheltering in London underground stations during air raids. Their bodies, heads and limbs are united in the undulating rhythms of Moore’s drawing: soothed, as it seems, by his hand. These fragile monuments of human endurance are in so many ways more powerful than his muckle bronze sculptures.

Drawing records what painting may overlook. Think of Rembrandt’s infant learning to walk, little wrists supported by two doting women; or his baby mussing the remaining hair of a patient old man. There is a breathing immediacy to every sketch. Rembrandt’s young wife Saskia having her hair combed, falling asleep or looking seductively back at her husband, a dog peeing, two friends dropping by, all dashed off with intense concentration like phrases in a diary.

Rembrandt takes a walk in the country, in 1664, and sees a teenager dangling from a gibbet, hanged for killing her landlady by accident. The features of her poor face are barely formed, her socks are full of holes. What made him draw the scene is surely the same compulsive passion for the world in all its truth, beauty and injustice, an almost militant naturalism that drives him to draw his own ruined face, sinking into lonely age.

Would we know Rembrandt’s mind so well without the drawings, many of them discovered in private folders after his death? It is miraculous that so many works of art on fragile paper – and in such fugitive media: silverpoint, chalk and pastel, fading pencil and chalk – have actually survived. Drawings are lost to mildew, flames, house moves, the over-scribblings of others, or outright self-destruction. The Italian master Bernini tore a magnificent self-portrait drawing with his mistress in two when she had the gall to leave him. Michelangelo destroyed many drawings in the last months of his life.

An assistant described Michelangelo around this time standing barefoot and drawing for hours with a compulsion that caused him to pass out. Those late chalk images, revised again and again until they appear quite spectral, are of Christ’s death, and feel like murmured prayers. The medium and scale are as potent, for Michelangelo, as any Sistine-sized fresco. And almost the smallest image among his drawings is his greatest emblem – the hand of God reaching out to Adam in The Creation. Not much bigger than an inch, but a lightning bolt of pure conception. The hand is drawn from the life; perhaps it was Michelangelo’s own.

To the modern eye, these drawings are not just provisional images but autonomous works of art. The idea of drawing as mere rehearsal surely went out with Michelangelo and Leonardo. It is true that some later artists kept their drawings hidden. Gauguin was horrified when a critic asked to see his sketchbooks. “My drawings? Never! They are my letters, my secrets.” But even in the Renaissance, when paper finally became readily available, artists gave or sold their drawings to collectors who admired their gift for illusion. Just to be able to draw a perfect circle, freehand, was a sufficient feat to attract a crowd in a Florentine court.

And so it remains. Children used to ask my painter father to draw circles, which he would then turn into planets, flying balls or fantastical fruit, whatever they wished. To see the world transformed into two-dimensional images, materialising on the page with a humble 2B, is after all to witness a form of magic.

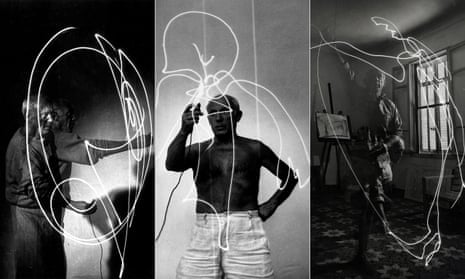

Drawing has lately diversified into performance art, with mass gatherings of people drawing together, or artists creating works live in front of an audience. But the precedents run back for ever. Picasso drew live, on glass, cameras on the other side filming the event. In the 18th century, the French painter Watteau made many drawings of dancers, actors, wanderers, fellow artists – his intimate circle. Airy and deft, the wiry line moving nimble across the page, these chalk drawing were more than just a form of private rehearsal, they were public performances in themselves. Watteau kept them in volumes and took them for show wherever he went. They were coveted, and sold, during his lifetime.

If it weren’t for a rococo frill round one wrist, Watteau’s drawing of hands would look as contemporary as the same subject drawn by Manet, Van Gogh or Picasso. Drawing transcends both era and time. Even the hoariest old master can look up-to-the-minute when drawing; and a drawing that took days to finish can look as fresh as one made in seconds.

To draw is to see, to learn, to understand. It is thought on the page; pure discovery, in John Berger’s phrase. It may describe the story of its own making, the trials and errors and corrections, the line hurtling or slowing, hesitant or incisive, perhaps finally triumphant. It gets to the page live and direct, brain to nib or sharpened tip, without the encumbrances of any other media. It is a tradition, and yet not a grand one; the poor may do it as well as the rich. In the 20th century it expands to meet every new movement: cubism, abstract expressionism, minimalism, pop. Drawing is evergreen, always renewing itself.

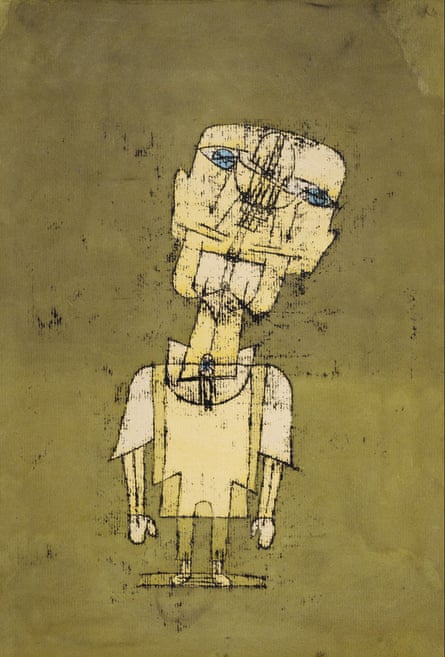

Taking a line for a walk, Paul Klee called it, as he put drawing through its paces from the most elementary forms. A dot is an eye, a mouth or the moon. Two more and a landscape appears. The dots turn into a line, which becomes a tightrope, a street, the steady surface of a lake or the perch for his twittering avian assembly.

Three lines stream across a page and a river appears, eddying with the slightest linear fluctuation. A triangle produces a pyramid or a passing yacht. Klee makes worlds with the simplest of marks. Pictograms, hieroglyphics, high art: his scintillating visions fuse the ancient with the modern.

Jackson Pollock loved Klee’s spindly black lines and his scratchy irreverence. Picasso studied Goya’s graphic art from first to last. Any canon of classic drawings would surely include both artists, along with hundreds of other masterpieces by spectacular performers on paper.

Think of Dürer’s Praying Hands, in ink and chalk, rising to heaven like the hope they depict; or his first surviving drawing, made at 13, a self-portrait in silverpoint from the most complicated three-quarter angle. Think of anything by Leonardo, from the unborn child tucked inside its mother’s nutshell womb to Vitruvian Man whirling for ever in his own span. Or Holbein’s astonishingly descriptive line in portraits that capture the slightest anxiety in an eye, or glimmer of humour in a mouth, offstage characterisations that bring his sitters live and direct into our present.

Some people love Jasper Johns’s drawings, simply made with his fingers like our ancestors on the dark cave walls. Or the graceful drawings of Matisse, undulating like the female forms they depict. Or the marvellously spare lines of Ellsworth Kelly’s citrus fruit, as close to abstraction, almost, as his paintings.

Others prefer the strange nocturnal light of Seurat’s black Conté crayon sketches, scenes of Paris arriving through an atmosphere of complete mystery on to the fine-grained paper. Or the exquisite op-art rhythms of a Bridget Riley drawing, swaying or sparking on the page. Or the explosive wall-scale works of Julie Mehretu, made on a crane, rushing towards some emergency climax.

Van Gogh’s drawings are, for me, masterpieces of originality and invention: lines streaking down the canvas on a dark day, so that you realised that rain was in some way comparable to drawing for the artist. The cedillas and hyphens, flecks and startling ink vectors that indicate the shining harvest, the heat, and the rising sky above. An infinite variety of notations.

Perhaps we all have a drawing that speaks a private language to us – Samuel Palmer’s secretive moonlit landscapes, Picasso’s Dove of Peace, David Hockney’s dogs, Eric Ravilious’s wondrous drawings of white horses, themselves pictures incised in a landscape. For me it is a tragicomic drawing by Goya, then aged 80, of an old man teetering along on two sticks which he holds as if he trying out newfangled skis. “Aún Aprendo” is written across the top; I am still learning…

So it is with drawing, the freest and the first of all art forms. You can do it with a fingertip in sand or the steamed-up windows of the bus. A scrap of paper plus a stub of pencil and you too may be an artist. A sketchbook, better still, is a world of infinite pardon where you can experiment for ever. Nulla dies sine linea – no day without a line, so says Pliny. Try again and again, absorbed in thought and line, going wherever you will, unbound and always still learning.

Draw Art Fair is at the Saatchi Gallery, London, 17-19 May; Who’s Afraid of Drawing? is at the Estorick Collection, London, until 13 June; Leonardo: A Life in Drawing is at the Queen’s Gallery, London, 24 May-13 Oct; Portrait of an Artist: Käthe Kollwitz will be at the British Museum, London, 12 Sept-12 Jan 2020

Why I draw: two writers and a film-maker on what drawing means to them

Deborah Moggach, writer: ‘Whenever I moved into a new place I’d paint murals on the walls… even bad murals make a room rather magical’

Both my mother and sister were children’s book illustrators, so I grew up drawing and painting. Strangely enough, in the last 20 years or so I stopped, which is an awful shame – it was something to do with writing books and bringing up children and everything getting too complicated. But I’m quite visual – I can always see the scene in a novel when I’m writing: I can see the room and the pattern on the carpet.

I used to write longhand on the right hand side of an A4-sized ring-bound notebook, and on the left hand side I’d draw grotesque faces with huge noses and crinkly hair and wrinkles, or sometimes beautiful, young, naked women. I’d have these creatures crawling all over: they’d be my sort of subconscious page, where my brain would loosen its connections. I find it very useful to have that arrangement, it helps with concentration. They weren’t an illustration of what I was doing, it was more a voyage into a fantasy world.

Whenever I moved into a new place to live I would paint murals on the walls as it saved on buying pictures: even if murals are quite bad, they make a room rather magical. I would paint Douanier Rousseau jungle scenes with herons and zebras all over the walls. I also once muralled a Renault 4 car. The other thing I used to do was copy Dürer etchings line for line: the finished product may have been absolutely hopeless but the process was the thing. Interview by Kathryn Bromwich

Deborah Moggach’s novel The Carer is published by Tinder Press on 11 July, £16.99. To pre-order for £14.95 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

Jonathan Lethem, novelist: ‘The thing about drawing that’s so different from writing is that it’s a body action’

My dad’s a painter: a lot of my baby pictures are me standing wobbly in my diapers beside him in the studio. I ended up going to a special music and art school in New York City when I was 14 as a prodigy painter – it seemed to be my natural identity. But after going to college I started writing my first novel and that toppled my life as a visual artist instantly. The thing paintings or drawings do least well is depict the passage of time, and I was always frustrated when I was drawing because I couldn’t make stories unfold in time the way I wanted to. When they were most realised, my drawings and paintings were full of narrative elements – characters, implicit situations, words. It was as though my storytelling was fighting its way to life.

I have a few pivotal artists who I identify with in my writing very strongly: the Italian surrealist Giorgio de Chirico, abstract expressionist Philip Guston, MC Escher, and also comic book artists like Robert Crumb and Jack Kirby. The thing that strikes me about drawing that’s so different from writing is that it’s a body action: you’re making something physical, with muscular action, with your arms and fingers. When you sit making stories with language, on a keyboard, it’s almost like you’re a kind of corpse, with these twitching fingers. That’s what I miss: the page, the line, which pencil you select, whether you need an eraser, whether you use a chunk of charcoal or perhaps coloured crayons.

In a funny way I’ve come back to it. I have two boys, for whom I began drawing when they were very young: cows and dinosaurs and monsters. Both of them have become kids who draw – when I was their age I was drawing a lot of amateur five-page comic books with my own superheroes in them, and they’re doing exactly that now. KB

The Feral Detective by Jonathan Lethem is published by Atlantic (£16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £15, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99

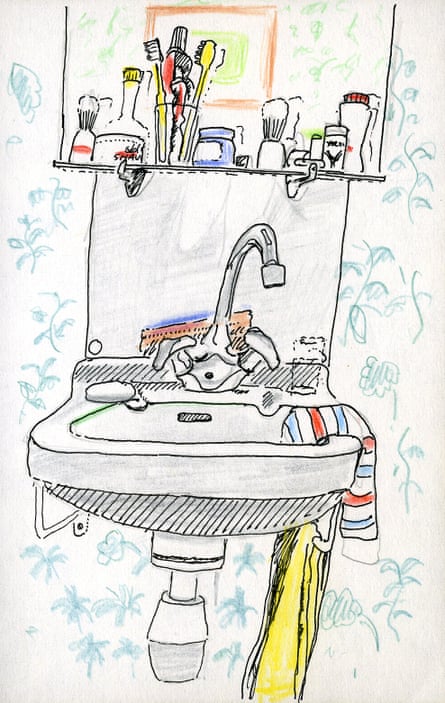

Mike Figgis, film-maker: ‘If you draw something you have more of a connection to it’

When I was about nine I started copying political cartoons from newspapers, and I’ve kept notebooks from my teenage years to the present day. Initially I tried to do very rigid drawings and then realised, partly through seeing drawings by Matisse and Hockney, that you can loosen up a little bit. I’m slightly fetishistic about stationery shops and notebooks. I like a rough surface paper, so it doesn’t bleed through. I’ve started using a Chinese water brush, which is incredibly satisfying, and I just bought a Japanese pen that’s got a thick, black ink flow which is fantastic for quick drawing.

I did an interview with John Berger before he died and he talked about the importance of the connection between the eye, the brain, the hand, the paper – that it’s a spiritual thing, psychologically very important. One of my sketches is a drawing of my mother I did at my father’s funeral – a photograph would never have been the same. When you’re 70 or 100, will you be looking back at your computer, which will no longer work, and you’ll probably have lost all those files anyway? If you draw something you have a much more vivid memory of that moment and more of a connection to it. There was a time when artists were expected to have a basic skill in all sorts of genres – drawing, photography, music – as a way of having the big-picture understanding. Sadly that’s sort of gone as we are urged to specialise in one thing. Actually, at the moment I’m making a documentary about Ronnie Wood, the Rolling Stones guitarist, who is very good at drawing, and I’ve focused on that in the film. KB

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion