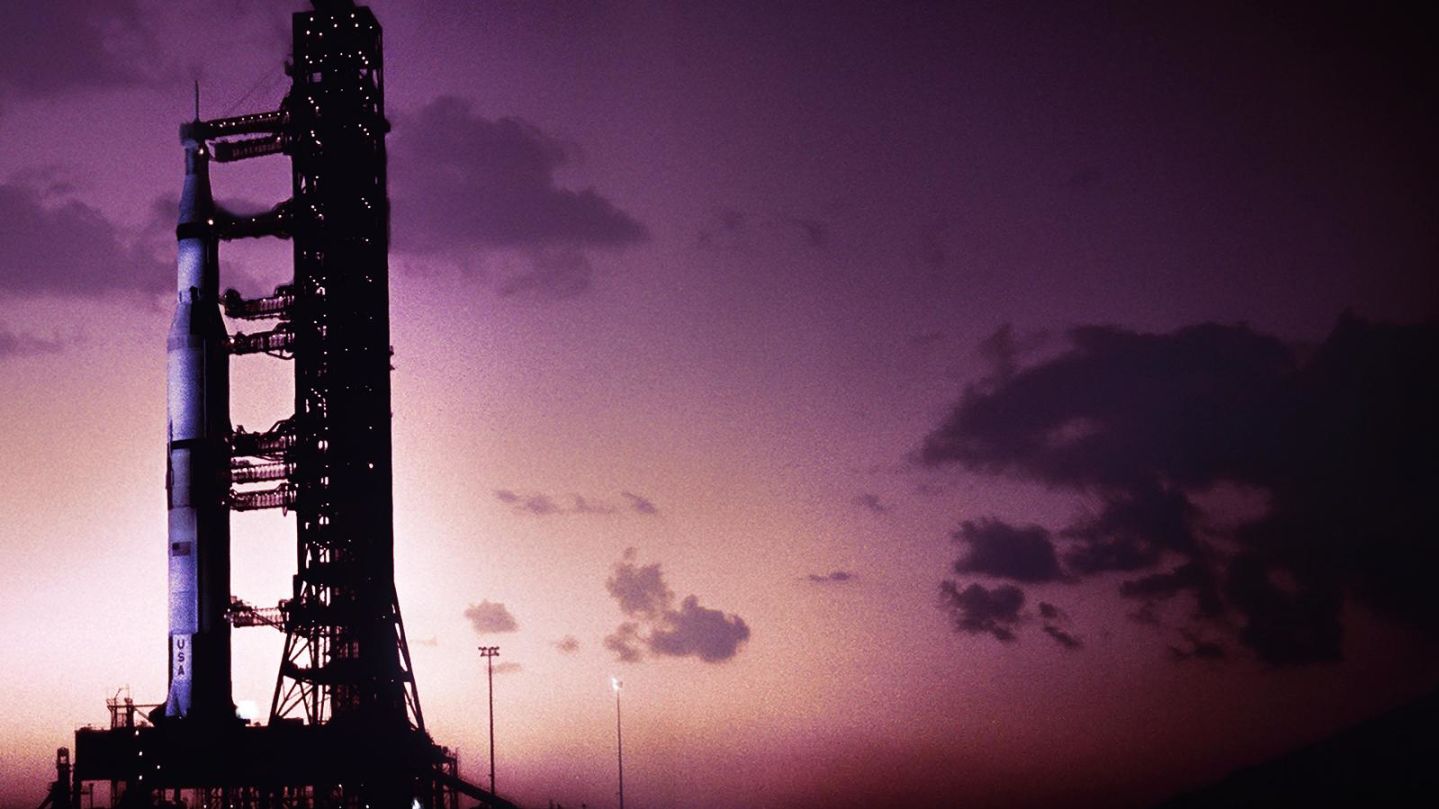

CNN Films’ “Apollo 11” explores the exhilaration of humanity’s first landing on the moon through newly discovered and restored archival footage. Watch the TV premiere of this documentary Sunday, June 23, at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

During the 1966 Gemini 8 mission, commanded by astronaut Neil Armstrong, an error caused the spacecraft to spin so violently that his and astronaut David Scott’s vision blurred.

It was set to be the first space docking in history between two spacecraft, Gemini 8 and the Agena, during NASA’s second human spaceflight program.

The astronauts were stuck in a loop, spinning faster and faster. “We have serious problems here,” Scott told Mission Control. “We’re tumbling end over end. We’re disengaged from the Agena.”

Despite the wild rotation, which would be enough to potentially cause a blackout, Armstrong was able to think quickly and use re-entry control system thrusters on the spacecraft’s nose to regain control. The mission was aborted, but Armstrong and Scott landed safely back on Earth.

It’s not unlike the harrowing failed launch that astronaut Nick Hague went through last year during what would have been his first trip to space. Two minutes after he launched in the cramped quarters of the Soyuz MS-10 capsule with Russian cosmonaut Alexey Ovchini, there was an anomaly with the booster, and the ascent was aborted, resulting in a ballistic landing.

“We were violently shaken side to side, thrust back into our seats as the launch escape system ripped us away from the rocket,” Hague said. “As all of that’s happening, you’re being shaken around; vision is blurry. I hear the alarm sounding and see the red light where the engine has had an emergency. I had the vivid realization ‘we aren’t making it to orbit today. We’ve been pulled off rocket, and we have to land.’ “

Upon re-entry, the two men faced an onslaught of G force, or the force of gravity, so strong that it pushed down on their chests. They had to breathe by using their abdomens to open their diaphragms. The astronauts also had to gather loose items so they didn’t become projectiles during landing. And they had to complete their landing checklist, speaking with Mission Control, as alarms blared around them.

On the flight recording, Hague can be heard speaking Russian, a language he learned as an astronaut candidate. Both men sound extremely calm throughout the entire process.

“You realize you’re in a tough spot. The thing you can do to give yourself the highest chance of success is focus and stay calm and do the things you were trained to do,” he later said.

Hague chalks it up to so much time spent training, going through every possible failure scenario – including one similar to what actually happened. They weren’t prepared for the physical sensations of a bounce-and-roll landing on the ground, yet Hague emerged from the capsule with a smile that surprised everyone.

Some of an astronaut’s success is training; some of it’s DNA.

It’s the ability to adapt, react quickly, knowing when to lead and when to follow, communicating effectively, remembering training and expecting the unexpected.

It’s the right stuff.

The first astronauts

In the beginning, NASA didn’t know what the qualifications for an astronaut should be. It needed people who understood risk, who could work under pressure and who could succeed in a dangerous environment full of unknowns. There were fears that a man would look out of the capsule window and see the Earth and freak out or that it might be impossible to swallow in zero gravity.

The very first astronaut class of 1959 was for the short-term Mercury program. In NASA’s plan for human spaceflight, one of the many issues that came up included security clearance. Although pilots were on the shortlist as potential candidates for the astronaut program, people with adventure experience had also been considered, like deep-sea divers, parachutists and even circus performers, according to NASA historian Bill Barry.

“In the very early days, every nut in the world rolled down the hallway and presented ideas, and some of them were really ludicrous,” Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins told CNN Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Sanjay Gupta. “Well, the air up there is very, very thin. It’s a vacuum. ‘Oh, we ought to get a mountain climber,’ and they say, ‘well, no, now some of these scuba divers, they get rapture of the deep, and they don’t want to come back to the surface, so we’re going to have to test for that a make sure our guys really want to return to Earth from space.’ And someone else said, ‘wait. Wait. It’s dangerous. It’s dangerous. We ought to get someone who’s accustomed to perils. We’ll get a bullfighter.’ “

It was suggested to President Dwight Eisenhower that requiring candidates to be graduates of an accredited test pilot school might cover all of the bases, Collins said.

“So immediately, what was an immense, just a gigantic pool of hopefuls got shriveled up into a couple of hundred, say, in the whole country,” he said.

Seven men were selected for Mercury, all test pilots. Their maximum height was 5 feet, 10 inches due to the size of the capsule, said Jennifer Ross-Nazzal, a historian at NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

The astronaut classes after Mercury would provide candidates for the Gemini and Apollo programs.

“The Right Stuff,” the 1979 Tom Wolfe book and the 1983 film, depicts the early astronaut programs and the test pilots who transitioned from flying in the sky to space. But is it, well, right?

“The selection process was rigorous,” Ross-Nazzal said. “They didn’t know what they would encounter, so NASA put them through procedures to see what the human body could tolerate itself. That part is probably fairly accurate.”

But the depiction of test pilots with cowboy-esque attitudes, which makes for a good story, isn’t the case.

Wolfe’s “depiction of the test pilots as mavericks, impulsive and fearless, is inaccurate,” Ross-Nazzal said, who has spent time with the test pilots. “The movie based on the book, while entertaining, really over-emphasizes these stereotypes.”

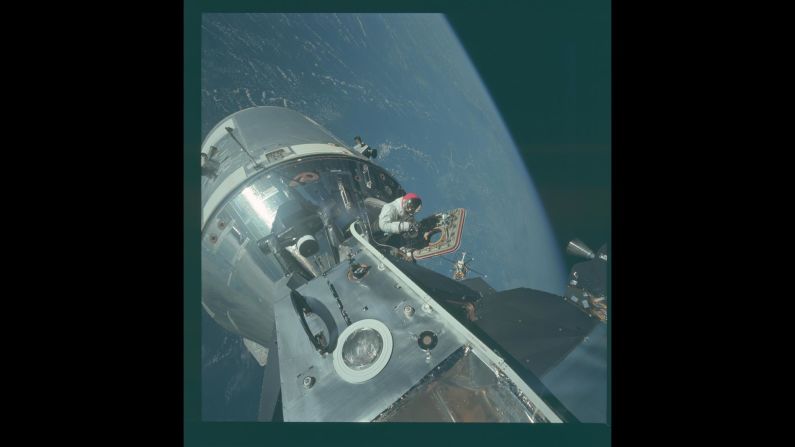

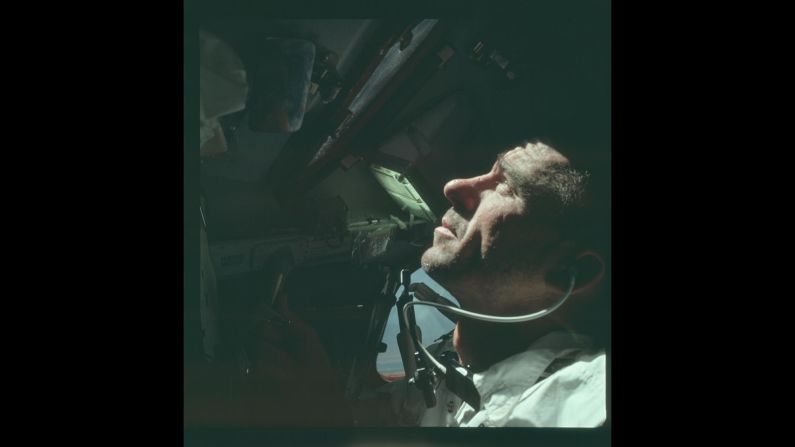

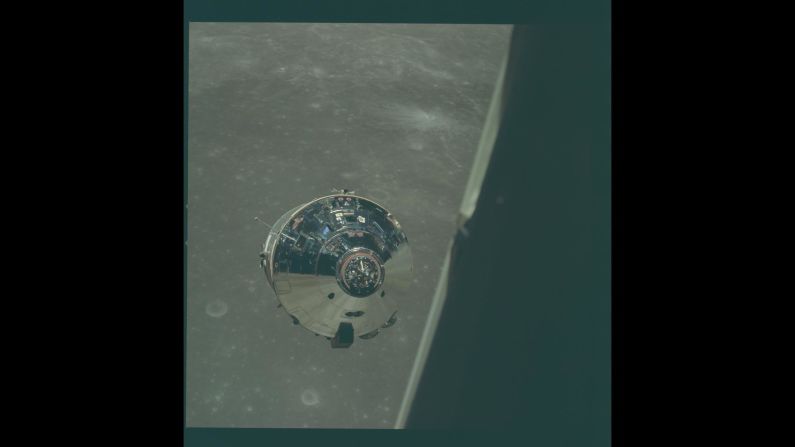

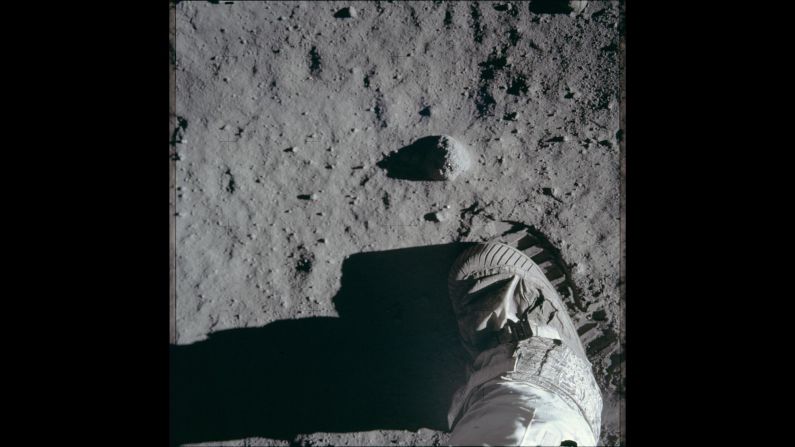

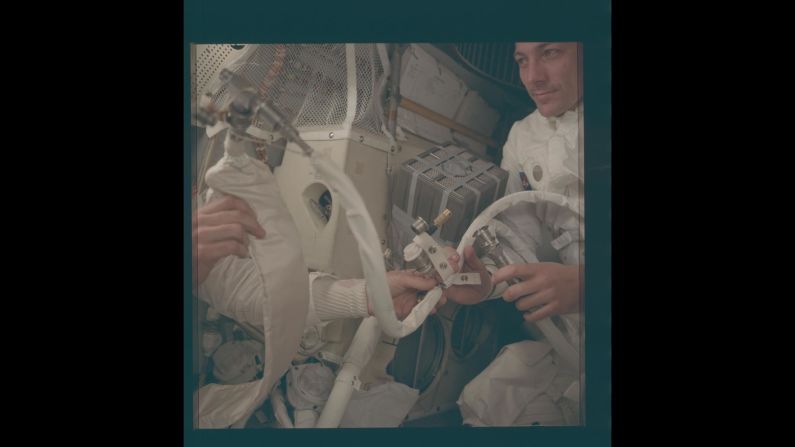

The photos Apollo astronauts took in space

In reality, the classes were constantly in motion, visiting NASA centers, taking on technical assignments like monitoring different aspects of Gemini and Apollo missions they weren’t flying, and piloting their T-38s to contract facilities. But the bulk of their time was spent simulating the mission that they were assigned to.

Hours were spent in classrooms, learning about propulsion, hardware and operations.

For the Apollo missions, astronauts spent time in the command and lunar module simulators, practicing rendezvous, docking, ascent and descent and talking to Mission Control. Simulation supervisors wrote scripts while they were in the module, putting the astronauts through the wringer to ensure that they – and the flight controllers – understood how their hardware operated and the procedures, Ross-Nazzal said.

The simulations were grueling, but the astronauts would later say that once their missions reached orbit, the training gave them a better appreciation for a smooth flight.

The lunar module was dangerous but necessary for navigating a moon landing.

On May 6, 1968, Armstrong performed his 22nd flight of Lunar Landing Research Vehicle #1 at Ellington Air Force Base. Five minutes in, he lost control of the vehicle due to a loss of helium pressure and was ejected 200 feet above the ground as the vehicle crashed and burned on impact.

Later, he would say that the Eagle, the famous vehicle that touched down on the moon, handled just like the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, which he flew more than 30 times before Apollo 11.

“That of course gave me a good deal of confidence – a comfortable familiarity,” Armstrong said at the time. “It was a contrary machine and a risky machine but a very useful one.”

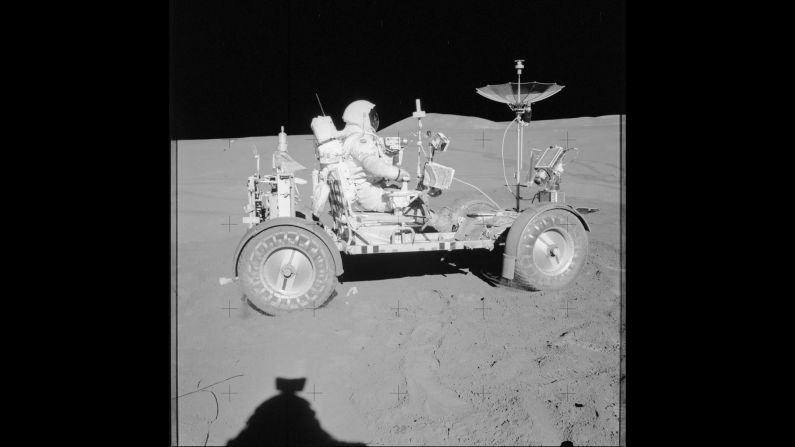

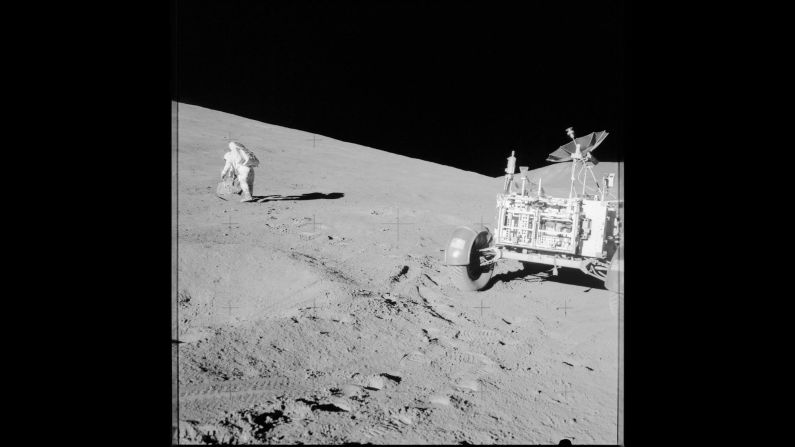

Astronauts preparing to land on the moon also took geology field trips to Hawaii, practicing field work and describing their surroundings to geologists. Experiments that would have to be set up on the moon had full run-throughs on the ground to find out what was possible in the heavy spacesuits.

The first astronauts were so immersed in training and preparing for their missions that some of them weren’t entirely aware of what was happening on the outside. Astronaut Alan Bean was so focused on preparing for Apollo 12 that he had to catch up on the events of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War years later.

Later, the test pilot requirement would fall away, and Harrison Schmitt, an American geologist, was trained as an astronaut who landed on the moon during the final mission of the program, Apollo 17.

The first astronaut class for the shuttle program in 1978 included more women and minorities as the needs of the astronaut program broadened to include more diverse skill sets. The shuttle missions would be longer and could carry as many as seven people, so they would have to work together as a team, Barry said.

The stresses of space

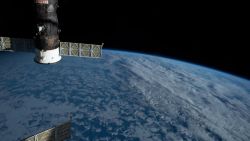

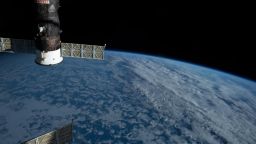

Today, astronauts have to prepare for long-term missions aboard the International Space Station. The usual mission length is six months, but more are taking on longer missions to help study the effects of long-term spaceflight on the human body. This will help prepare for the next wave of space exploration: returning to the moon and, eventually, a mission to Mars.

Life in zero gravity isn’t easy.

After more than 50 years of human spaceflight, researchers know some of the risks that it poses to the human body. Astronauts have to deal with a stressful environment, noise, isolation, disrupted circadian rhythm, radiation exposure and a headward fluid shift that happens when floating rather than standing on solid ground.

Space motion sickness occurs in the first 48 hours, creating a loss of appetite, dizziness and vomiting.

Over time, astronauts staying six months or more on the station can experience weakening and loss of bone mass and muscle atrophy. They also can develop blood volume loss, weakened immune systems and cardiovascular deconditioning since floating takes little effort and the heart doesn’t have to work as hard to pump blood. Those in their late 40s and 50s have also complained about their vision being slightly altered. Some have required glasses in flight.

Spending 340 days aboard the International Space Station between 2015 and 2016 caused changes in astronaut Scott Kelly’s body, from his weight down to his genes, according to the results of the NASA Twins Study. Kelly and his identical twin brother, Mark, have both been astronauts, but a unique opportunity was presented when Scott planned to spend a year on the space station while his brother remained on Earth.

The majority of changes in Kelly’s body, compared with Mark’s on Earth, returned to normal once he came back from the space station. A year in space caused Scott’s carotid artery to thicken, DNA damage, gene expression changes, a thickening of the retina, shifts in gut microbes, reduced cognitive abilities and a structural change at the ends of chromosomes called telomeres. But it did not permanently alter or mutate his DNA.

Going forward, NASA is focused on the key threats to humans traveling in space: isolation and confinement, radiation, distance from Earth, hostile or closed environments and fluctuating gravity.

The added stresses of a mission to Mars include years, rather than months, spent in space and an exacerbated sense of isolation due to the communication delay. The crew will need to be more self-reliant. Psychologists at NASA have introduced countermeasures to the confining nature of the space station by increasing the amount of communication with family members and links to culture, movies, music and news. They also send crew care packages, helping boost morale.

While the station astronauts need to feel secure in their training and ready to be called upon for any task, whether it’s bandaging up a fellow crew member or fixing a broken machine, they can’t do everything on their own. That’s where the non-technical requirements of a good astronaut candidate come into play.

“We need technical capabilities. We need the ability to pilot a vehicle. We need the ability to serve as a crew medical officer. We need other kinds of technical applications,” said James Picano, senior operational psychologist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

“But within all of those people, we need the capability to get along well with one another, to form a cohesive crew, to work cooperatively and to live effectively with one another. We’re not talking about finding superhuman people. They don’t exist. We’re talking about finding people who are psychologically competent, who are trained to work well together with one another and to manage the relationships.”

A key trait is resilience, or tolerating high degrees of stress without degrading performance or health, Picano said. Armstrong and Hague are just two out of many who have shown resilience in the face of errors or anomalies.

And at the heart of each astronaut, there’s probably a lifelong explorer who wants to be part of this quest to go beyond our own planet.

“They are motivated by this idea of challenge and this idea of adventure,” Picano said. “I think a sense of contribution, a sense of giving to the greater good of that explorer spirit, all goes a great way toward motivating people to take on things that a lot of people would not do.”

Selecting someone with the right stuff

The astronaut candidate selection board looks for characteristics and skills suited to the stresses of spaceflight. Once candidates are selected, an impressive training program educates them on every aspect of what they might need to do on a long-term space mission and relentlessly tests them on each potential scenario for failure and success.

When astronaut Megan McArthur applied in 1999, 17 candidates were chosen from 3,000 applicants. A record 18,300 applied to be astronauts in 2017, and 12 were chosen. McArthur is now on the selection board, along with other current astronauts, flight directors and the director of flight operations.

The board has a screening process to whittle down the large number of applicants to about 100 candidates whom they invite to Johnson Space Center. They want to get to know them in person through panel interviews, conversations and performance screenings. To practice hours-long extravehicular activities, called EVAs, the astronaut candidates practice in a football field-sized swimming pool that’s 40 feet deep with a model of the space station, practicing changing equipment and the choreography they’ll need in the absence of gravity.

Other times, like Hague, they spend hours in a simulator that looks like their spacecraft, practicing how to handle malfunction after malfunction.

The board is looking to see how they perform in team environments and on their own. Knowing when to lead and when to follow, as well as when to make that switch, is key. Are they trainable and able to pick up new skills? Do they have what it takes to perform, to assess their own needs and the needs of others?

Once the selected applicants become astronaut candidates, they go through intensive training: basic training in spacecraft systems, what a spacewalk might be like, how to work with robotics and tackling mission assignments. McArthur was a trained engineer who didn’t have an aviation background, but her program at NASA “built her up,” she said, breaking down everything system by system.

“That’s what the training is designed to do: to get you through those situations where you can’t think through but react and know you’re doing the right thing at the time,” McArthur said. “It provides you a discipline. You have to learn these systems, because your life will depend on them.”

And even as the selection process has shifted to include different screenings, the basics of what they’re looking for don’t change.

“The skills and characteristics of an explorer won’t change at all,” McArthur said.