Jailed mothers: The 'terrible damage' to children

- Published

About 17,000 children are separated from their mothers every year by the prison system in England and Wales, which has one of the highest rates of female incarceration in western Europe. Now some MPs say the courts may be denying the human rights of these children.

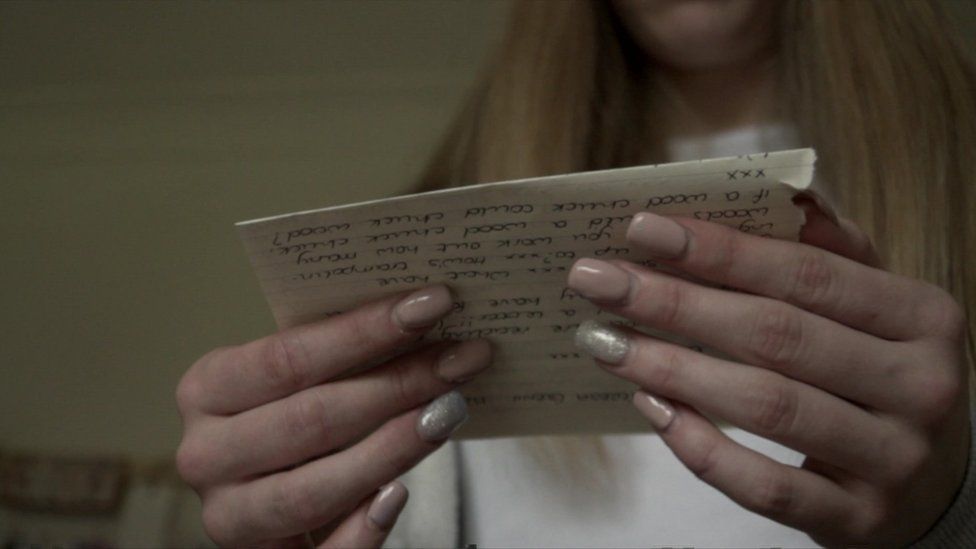

Katie was 11 when her mother was sent to prison, and she never even got the chance to say goodbye.

"I felt like I had been punished when my mum was sent to prison. I wasn't able to talk to her and I hadn't done anything wrong."

Her mother, Anna, had no time to make childcare arrangements before spending four months in prison for fraud offences.

In 95% of cases where women are imprisoned, children have to move out of the family home. Research suggests the separation and upheaval has a lasting impact.

"I remember feeling very lost. I was angry at the fact that I couldn't see her a lot," Katie says. "So I used to cry at school all the time. But no one knew what happened."

Even after they were reunited, Katie says she had nightmares about losing her mother again. Anna says Katie clung anxiously to her. "Even now, all these years on I struggle to move anywhere without her checking I'm there," says Anna.

With women more likely to be the sole carers of children, they face a "double punishment" in the court system, says Dr Shona Minson from the Centre for Criminology at the University of Oxford.

Many women are afraid to reveal in court that they are mothers because they think they will be judged more severely, she says.

In many cases, grandparents care for the child during the mother's sentence, Dr Minson says. But unlike foster care placements, they usually receive no support from the state.

"What is really important is that the state recognizes a responsibility for those children, whoever's fault it is," she says.

Unlike the family court system, the criminal courts are not expected to prioritise the welfare of children, although there are some protections under human rights law.

'An innocent child'

That is the focus of an inquiry by Parliament's Joint Committee on Human Rights, chaired by the Labour MP Harriet Harman.

She says when a mother is imprisoned, their children's education suffers, they develop a fear of the authorities and some family relationships never recover.

"When you've got the terrible damage inflicted by something the state is doing to an innocent child, you really should have to justify that," she says.

The committee is conducting an investigation of the right to family life for children of imprisoned mothers, examining whether planned government reforms go far enough.

Current guidelines to take into account the impact on dependent children are inconsistently applied and inadequate, Ms Harman says.

Instead, the government should legislate so "the interests of the child are paramount" in criminal sentencing, she says.

Lives set back

Women are more likely to be imprisoned for non-violent offences and more likely to receive short sentences of 6 months or less. Ministers have acknowledged that these sentences are less effective than community service.

But Lord Woolf, the former Lord Chief Justice, says judges may be forced to make sentencing decisions without all the information they need. "The probation service is stressed. So many services are stressed," he says.

Pre-sentence reports by probation officers, which can include details of dependent children, have declined in use in the last ten years, with a recent report finding they were completed in less than a quarter of cases.

Justice Secretary David Gauke says he wants to reduce the number of women being given short sentences for non-violent offences because "lives are set back and in particular the lives of their children are set back".

But he says the biggest challenge is in finding effective alternatives to prison, when many men and women receiving short jail sentences are "prolific minor offenders" for whom "community sentences aren't working".

'The most shameful moment'

One mother, Rose, experienced first hand how inconsistent the courts can be in sentencing. At her initial trial for drug offences, she was given a suspended sentence after a detailed consideration of the impact on her children.

"He reduced the sentence by around 30% for my children, because I was the sole carer and they would struggle," she says.

But in the court of appeal, where her sentence was overturned, she believed her motherhood counted against her. She spent 12 months in prison.

"When the prosecution was talking about the case, the first thing mentioned was that I was a mother of two. That was the killer for me - that was the most shameful moment," she says.

"I'm a mother and how dare I do such a thing and not think about my children?"

She was sent to prison with this message from the judge: "While impact on children is important, parenthood cannot be used as a trump card to avoid jail."

Names have been changed to protect the identities of families.

- Published29 September 2018

- Published4 February 2019

- Published30 March 2017