Paleontologists are trying to dispel the myth that a world crowded with dinosaurs left little room for mammals and their relatives.

According to the myth, mammals and their kin, together known as mammaliaforms, remained tiny, mouse-like, and primitive. The myth posits that mammals didn’t evolve diverse shapes, diets, behaviors, and ecological roles until the K-Pg mass extinction event 66 million years ago killed off the dinosaurs and “freed up” space for mammals.

The false narrative has wormed its way into books, lectures, and even scientific papers about this long-ago era.

“This is a very old idea, which makes it very hard to defeat,” says David Grossnickle, a postdoctoral researcher in the biology department at the University of Washington. “But this view of mammaliaforms simply doesn’t stand up to what we and others have found recently in the fossil record.”

Correcting the record

Grossnickle is the lead and corresponding author of a review article in Trends in Ecology & Evolution that summarizes the latest fossil evidence for an alternative view: Mammals and their relatives have actually undergone three significant “ecological radiations” in their history.

In evolutionary biology, a radiation occurs when a particular lineage invades and adapts to new ecological niches. In each of the radiations discussed in the review, mammaliaforms diversified from insect-chomping, rodent-like ancestors and adapted to a variety of ecological niches. New species arose that, for example, could climb, glide, or burrow—and ate more specialized diets of meat, leaves, or shellfish.

Two of these three ecological radiations of mammailaforms occurred during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods when dinosaurs were thriving, according to Grossnickle and coauthors.

The coauthors summarize the three ecological radiations, each of which involved different groups of mammaliaforms:

- The oldest mammaliaform ecological radiation ran from 190 to 163 million years ago in the early-to-mid Jurassic Period—amid the breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea—and involved the first true mammals and their closest relatives.

- A second ecological radiation of mammals began 90 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous Period, shortly after flowering plants evolved, and ended at the K-Pg mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

- The Paleocene-Eocene radiation began 66 million years ago around the time of the K-Pg event and ended about 34 million years ago, and led to the establishment of all the major lineages of placental and marsupial mammals alive today.

Each ecological radiation generated new varieties of mammaliaforms from more primitive, insect-eating, rodent-like ancestors. Many of the diverse forms that arose during the Jurassic and Cretaceous resemble species alive today, such as badgers, flying squirrels, and even anteaters. But these dinosaur-era mammaliaforms are not the direct ancestors of their modern counterparts.

“These same ecological adaptations—for gliding, climbing, eating diverse diets—have evolved repeatedly in the history of mammals and their close relatives,” says Grossnickle.

Ancient mammals

Mammaliaforms that arose during the Jurassic radiation included the semi-aquatic, beaver-like Castorocauda; Maiopatagium, which likely resembled today’s flying squirrels; and the tree-climbing Henkelotherium. These lineages died out by the mid-Cretaceous Period—a time of general decline for early mammals and their relatives, likely due to climate change and the relatively rapid turnover of whole ecosystems.

The Late Cretaceous ecological radiation followed this period of decline, and saw the rise of new forms of mammals. These included the badger-sized Didelphodon, a marsupial relative with the strongest pound-for-pound bite force of any known mammal, as well as Vintana, a herbivore with some skull features similar to sloths. These diverse groups of mammals perished alongside dinosaurs in the K-Pg mass extinction.

“The presence of this diversity of mammaliaforms in the Jurassic and Cretaceous overturns a classical interpretation of how mammals evolved,” says coauthor Greg Wilson, an associate professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture. “This new interpretation was really made possible by new fossil discoveries over the past two decades in places like China and Madagascar.”

The Paleocene-Eocene radiation of mammals, which began around the time of the K-Pg event, generated the ancestors of today’s marsupial and placental mammals—from kangaroos and zebras to blue whales and humans. This radiation’s strong connection to today’s mammals may explain how the myth arose that mammals remained static and primitive in the time of the dinosaurs, according to Grossnickle.

“But focusing on the Paleocene-Eocene radiation gives a distorted view of the history of mammals,” says Grossnickle. “It ignores many of the other groups of mammals and their relatives that were diversifying millions of years before then.”

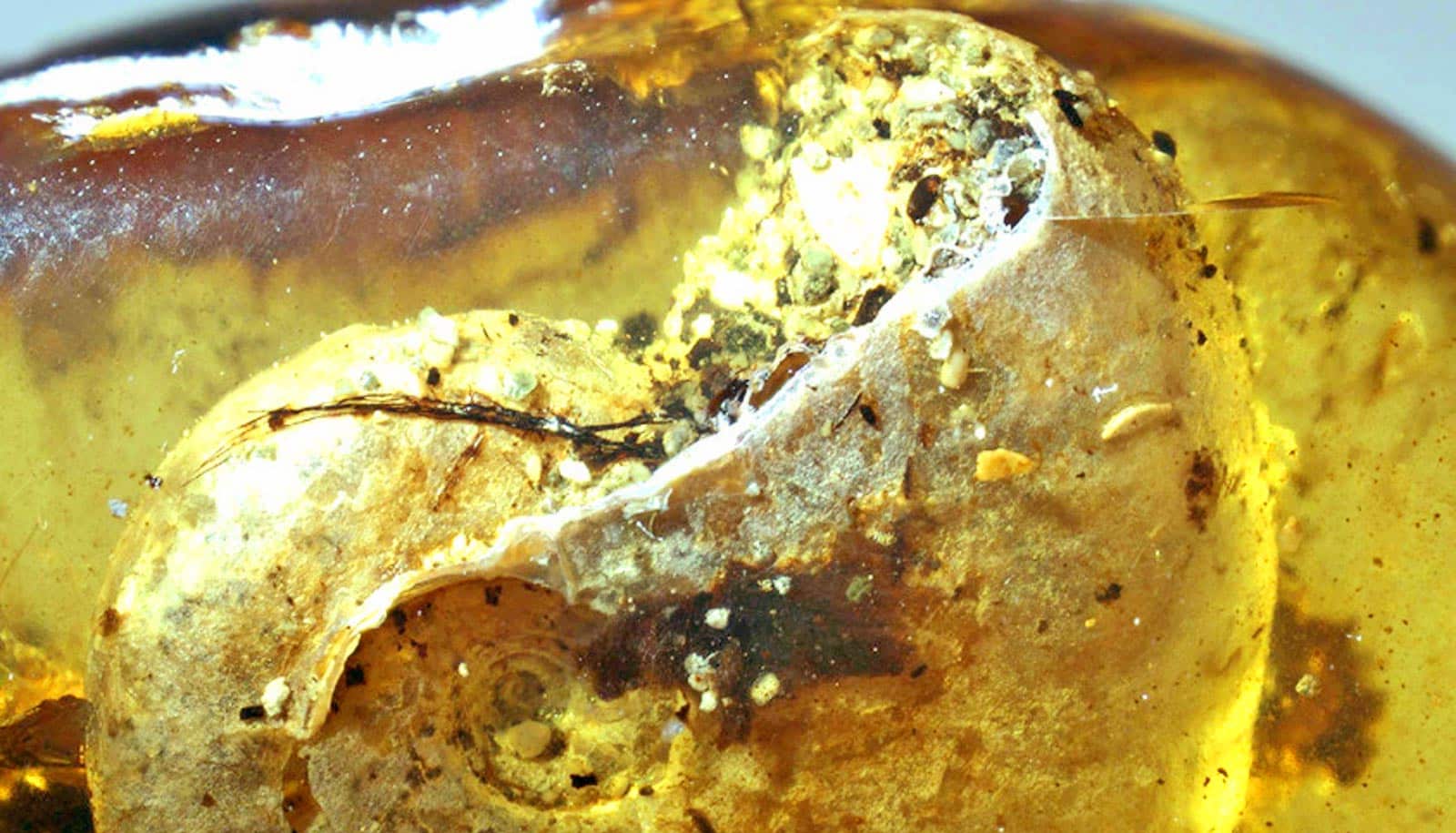

Fossil discoveries over the past quarter century support the view the researchers summarized. Dinosaur-era mammaliaforms that were once known by only a single tooth or a few bone fragments are now represented by more-complete skeletons, which show the diversity in body shape, size, locomotion, and diet.

“Now we can start to see the huge diversity of mammals and their relatives who lived alongside the dinosaurs,” says Grossnickle.

Stephanie Smith of the Field Museum in Chicago is also a coauthor.

Source: University of Washington