In a family photograph taken by his father in 1903, nine-year-old Jacques Henri Lartigue stands on a path in the Bois de Boulogne, in front of his mother and grandmother. He is grinning mischievously and clutching a beloved Jumelle box camera that had recently been given to him by his father. In the next few years, Jacques will constantly record the world around him, photographing his bedroom, making portraits of uncles and cousins, and framing his older brother, Zissou, as he leaps into the air from a boat.

Another 60 years will pass, however, before the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York hosts the first exhibition of his work, belatedly bestowing on Jacques Henri Lartigue the recognition he deserves as one of the great innovators of 20th-century photography.

When the celebrated American photographer Richard Avedon saw Jacques Henri Lartigue’s work for the first time on the eve of the MoMA show in 1963, he wrote to his compatriot to express his gratitude: “It was one of the most moving experiences of my life… You brought me into your world and isn’t that, after all, the purpose of art?”

The world Lartigue created with his camera was a reflection of the one he was brought up in as a privileged, pampered boy in a family environment that was both bourgeois and carefree. His father Henri, a self-made businessman, insisted that neither Jacques nor Zissou attend school, instead recruiting private tutors whose main aim was to keep Henri’s offspring amused. He once said: “I have plenty of money. My children should learn how to spend it.”

Later, Lartigue’s name would become synonymous with a certain kind of ritzy glamour and elegance, epitomised in his countless images of his lover, Renee Perle, whose sultry beauty captivated him. In the 1920s and early 1930s, he was known primarily as a society photographer, shooting the rich and beautiful in the resorts along the Côte d’Azur, where he felt effortlessly at home. The life he lived seems to have been as gilded as the lifestyles of the film stars, models, socialites and playboys he photographed.

In her new book, The Boy and the Belle Époque, Louise Baring concentrates on Lartigue’s childhood and teenage years, the majority of the photographs included having been taken before he turned 18. She traces a formative journey that begins in the early 1900s, when the Lartigue family lived in opulence in Paris and their country retreat in the Auvergne, and continues until 1914, when the outbreak of the first world war signalled the end of the belle époque.

Lartigue’s life during this period pertains to the arc of a classic French coming-of-age novel. He was an instinctively gifted, voraciously curious prodigy who found his creative medium as a child, and was sustained by it throughout his formative years and into his adult life.

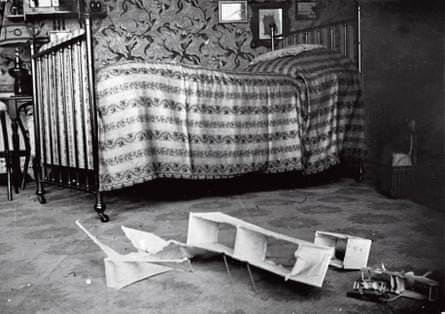

From the start, it seems, Lartigue had one eye on posterity, creating photo-albums and journals of the things he witnessed. Aged 11, he photographed his bedroom from ground level, furniture and a mirror looming over his toy racing cars.

More often, as the array of model racing cars suggests, he was drawn to movement, and, as a child, often photographed relatives and servants jumping off walls and over tables to his instructions. In one memorable image, he captured his cousin Simone taking a tumble from a homemade scooter. His most intriguing early subject, however, was Zissou, a daredevil and a dandy, who built and raced his own go-karts, tearing around the grounds of Chateau de Rouzat, the family’s country retreat, in goggles and a tailored suit. Zissou was the eccentric action man, while Jacques, as Baring puts it, was “a sensitive child who became a lifelong spectator”.

Later, he would photograph speeding racing cars in a blur of motion and beautiful socialite women framed like exotic creatures in closely cropped compositions. When these images were belatedly discovered and exhibited decades later, they attested to Lartigue’s instinctive embrace of what later became known as the snapshot aesthetic, a term loosely applied to 60s iconoclasts such as Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, who disregarded the rules of formal composition. Back in the early 1900s, when Lartigue embraced blur and movement, his approach was so singular that it amounted to what Baring calls “a new visual language of the 20th century”.

On 29 May 1910, Lartigue, then 15, began a new adventure in a new setting, arriving at the Avenue du Bois de Boulogne in Paris with an unwieldy folding plate camera. His aim was “to photograph the ladies in the most outrageous and beautiful hats”. Back then, the Bois de Boulogne in early summer was an open-air promenade, where society women paraded their style. They often crossed paths on the Allée des Acacias with the more bohemian and even more fashionable women of the Parisian demimonde: actors, dancers, musical hall stars and “grand cocottes” – courtesans like Liane de Pougy, a friend of the novelist Colette, and Émilienne d’Alençon, a great beauty who would later become Edward VII’s lover.

Although cold-shouldered in public by respectable members of Parisian high society, these demimondaines, writes Baring, “set the style, deciding which couture creations would rise or fall in the coming season”. Lartigue captured them all, often startling his exotic subjects with the loud click of his camera’s shutter. The results are fascinating, a record of a time and place when this sartorial exhibitionism was simply another diversion in, as Colette scathingly put it, “the bustling lives of people with nothing to do”.

At times, Lartigue inevitably comes across as a proto-paparazzo. More often, though, he captures vignettes that speak volumes about the elastic social mores of the belle époque. His snatched portraits, for all the period detail they capture, seem, like his previous images of speed and movement, oddly contemporary. The blur, the often fantastical silhouettes, the sideways glances, the way he crops his images so that his subjects loom large – and even more exotic looking – in the frame, point to a singular sensibility that was at odds with traditional composition.

Throughout this period, his love of speed and movement remained. He photographed the early French pioneers of flight, Gabriel Voisin and Louis Blériot, as they risked life and limb in an aerodrome near Paris. At the 1912 Grand Prix in Dieppe, he made one of his most famous early photographs, freeze-framing the rear of a Delage racing car as it sped past him at close range. The driver clutches the wheel as observers on the other side of the track appear as leaning shadows, their blurred outlines evincing the sense of motion that Lartigue set out to capture. In retrospect, all those childhood days snapping Zissou on his go-karts and his cousins leaping through the air seem to lead to this defining moment.

If Lartigue was a photographer of the age of speed and modernity, he was not a man of action when it came to the war, which, for the main part, seemed to pass him by as if happening elsewhere. As France ordered general mobilisation, he retreated with his family from Paris to the Auvergne and the sanctuary that was Chateau Rouzat.

“The war inevitably made us unhappy,” he wrote in a secret diary, “but it was happy all the same… I played sports and we still amused ourselves.” There is a single image in the book that suggests the unfolding horror: a platoon of marching soldiers silhouetted against a grey sky as a spindly aeroplane flies overhead. The war inevitably curtailed his carefree life, writes Baring, but “Lartigue emerged intact, plunging into life with the passions of a child, refusing ever to grow up”. That childlike optimism would fuel his life and his photography for decades to come.

Lartigue: The Boy and the Belle Époque by Louise Baring is out on 16 April (Thames & Hudson, £28). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15