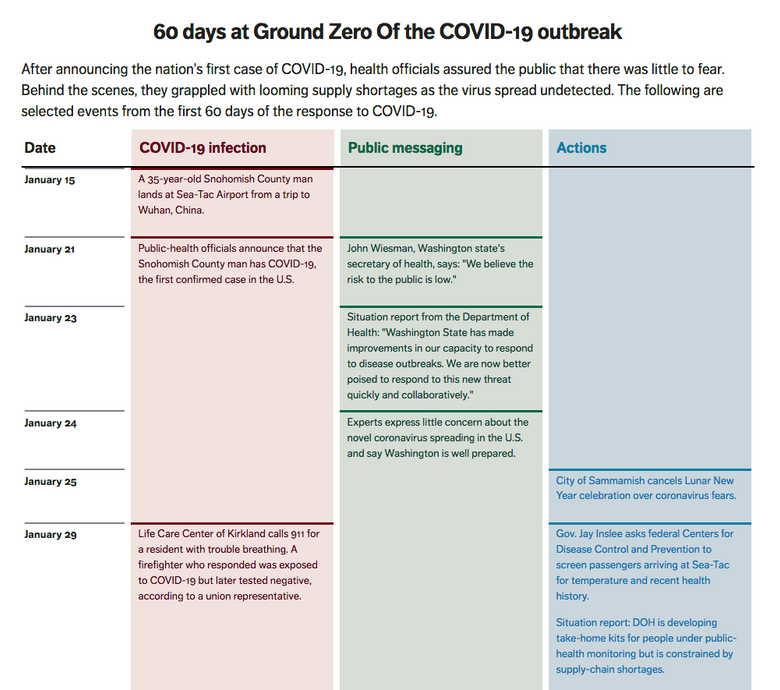

The Sammamish Lunar New Year Celebration was one day away, but as Jun Wang and her companions unpacked boxes of red lanterns for the Jan. 25 festival, they couldn’t ignore the panic all around them.

For weeks they’d heard reports from family and on Chinese social media about a virus terrorizing Central China, where several had relatives. Now the new coronavirus had landed at their doorstep. On Jan. 21, Washington state had announced the nation’s first confirmed case of what would come to be called COVID-19: in a Snohomish County man who had returned from Wuhan, the epicenter of the crisis.

“What China goes through, we will all go through,” Wang, principal of the Sammamish Chinese School, later said.

Most of the other participants in the popular event had already pulled out. In deference to the Chinese community, the city canceled the festival, making it perhaps the first event in the U.S. to be canceled over coronavirus fears.

Public-health professionals weren’t especially worried at the time. They were monitoring people who had had contact with the Snohomish County man, and were watching hundreds of other travelers, checking them for signs of illness, testing dozens who met the criteria and finding nothing.

For more than a month, officials in Washington state assured the public that the risk was low, unaware that they had already lost the first battle. The virus was loose.

Even as Washington state appears to have made progress in slowing the spread of the virus, a Seattle Times reconstruction of the early response points to an underfunded public-health system that relied on a series of fragile assumptions.

Nursing homes would do their own surveillance for outbreaks, and would promptly alert authorities. Federal agencies would be ready with diagnostic test kits. Health care workers and first responders would get the protective gear they needed. And when the state’s own warehouses were empty, the federal government would step in to fill the void.

In each case, the expectations were misplaced.

Compounding federal testing fumbles and short-staffed local health departments, the virus’s arrival in the height of flu season provided the perfect camouflage for it to spread undetected, taking one life after another and turning a Kirkland nursing home into the single deadliest front in a national crisis.

Washington state’s experience also offers a cautionary tale for public-health experts, who for weeks downplayed the risk of the novel coronavirus — and then in a matter of days strained to persuade the public to avoid all possible human contact.

“First in the nation”

The man who would become known as Patient Zero in the U.S. tested positive for COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, five days after landing at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. The public-health system swung into action.

At Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, the 35-year-old was ushered into an isolation chamber — which sucked in air to prevent the virus from spreading — and was tended by health-care workers wearing helmets with respirators, plus face masks and two pairs of gloves.

For all the apparent urgency, public officials and many independent experts were sounding a consistent message: The American public had little to fear. Authorities had the matter well in hand.

“There is nowhere in Snohomish County that I would be reluctant to take my new granddaughter or my family members,” Gov. Jay Inslee said at a Jan. 21 news conference announcing the case.

“No one wants to be the first in the nation in these types of situations, but these are the types of situations that public health and its partners train and prepare for,” said Dr. Chris Spitters, the health officer for the Snohomish County Health District, on that day.

President Donald Trump, speaking to CNBC the next day, said: “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s — going to be just fine.”

The strain was new, but experts in infectious diseases knew a lot about its genetic family. Coronaviruses, named for their spiky appearance under a microscope, were known to be spread only by people with symptoms of the disease.

Public-health officials traced more than 60 people who’d had close contact with the infected patient, according to state documents and officials. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tested all of them. None had COVID-19.

The health officials expanded their surveillance to travelers returning from China with fever and respiratory symptoms. Only people who met those criteria would get a test.

By late January, the weaknesses of this approach were becoming clear. Doctors in Germany had found that people transmitted the virus without having symptoms themselves. CDC experts were probing how common this was, even as they worked out kinks with diagnostic tests for the virus.

The state Department of Health (DOH), taking cues from the CDC, said there was no evidence the virus was spreading in Washington.

“We were looking, using the best tools we had, and we hadn’t found anything,” Dr. Jeff Duchin, the health officer for Public Health – Seattle & King County, later said.

A genetic analysis of the virus by Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, later would find similarities that suggested Patient Zero likely transmitted it to another person. This second person would have acquired the virus before the first patient went into isolation on Jan. 20.

The virus was already moving from person to person, but no one knew.

Undersupplied

Not long after the first case had been identified in Snohomish County, staffers with the Department of Health began surveying the state’s reserves of personal protective equipment, or PPE — the masks, face shields, gowns and gloves that serve as a crucial barrier for health-care workers and first responders tending to highly contagious patients.

Inside a 6,834-square-foot department warehouse in Thurston County, with three levels of storage racks, the staffers found a cache of 600,000 N95 masks.

There was a complication: The masks were left over from the H1N1 pandemic in 2009 and had passed their expiration dates. By Feb. 4, state officials had consulted with the U.S. Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response about the shelf life of N95 masks. The CDC advised they couldn’t be used to care for patients, state officials said.

None of this was wholly unexpected. The department had drilled for such events, crafting a 90-page plan for responding to a pandemic. While hospitals were expected to provide “appropriate PPE,” if supplies ran low, the plan called for tapping into the federal government’s reserve of medical supplies and equipment: the Strategic National Stockpile.

The stockpile stores drugs and medical equipment in the event of a large-scale epidemic or emergency that exhausts local supplies. Its record wasn’t perfect: During the H1N1 response, when the CDC tapped its reserve for face masks, respirators, gowns and gloves, it failed to supply states with materials they needed and gave them things they didn’t lack, according to an audit by the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress.

“PPE supplies are tight,” John Wiesman, Washington state’s secretary of health, emailed senior officials in health, emergency management and the governor’s office later that month.

The plan was to order more supplies from the state’s vendors, work with hospitals to conserve PPE and — if the governor had to invoke emergency powers — seek help from the federal stockpile.

A cluster of emergencies

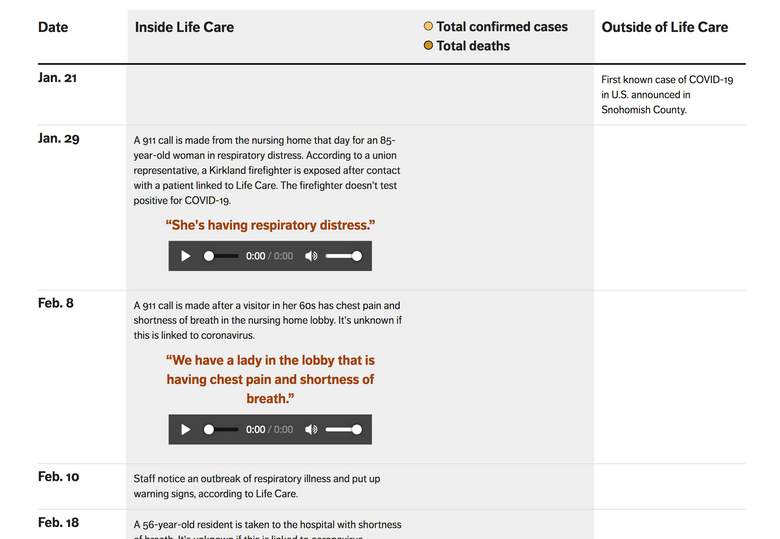

On Feb. 19, a state nursing home inspector paid a visit to the Life Care Center of Kirkland to investigate its handling of a suspected tuberculosis case.

The sprawling, single-story building, tucked behind a row of pines a mile from Lake Washington, is one of the largest nursing homes in the state, capable of accommodating up to 130 residents. It had the highest overall rating from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The inspector found that the nursing home’s infection-prevention measures were in order. The sick resident didn’t have tuberculosis. “No residents are in isolation,” the inspector noted.

Without knowing it, the inspector had wandered into the hottest zone of COVID-19 transmission in the nation. (The inspector self-quarantined for 14 days after the discovery of the outbreak, didn’t visit any facilities in the intervening period, and hasn’t developed any symptoms, an agency spokesman said.)

It had been more than a week since nursing home staff noticed that a respiratory illness was spreading. Eight residents had symptoms of pneumonia or respiratory illness, and at least some tested negative for the flu, federal records show.

Nursing homes are required to report outbreaks within 24 hours to public-health authorities, who lack the manpower to actively ask about such cases.

“We rely on these facilities to monitor for illness and proactively report to us,” said a spokeswoman for Public Health – Seattle & King County (PHSKC).

Life Care didn’t report the outbreak, or stop new admissions, until two weeks after noticing it.

“This was not setting off COVID alarm bells for us; this was setting off pneumonia and influenza alarm bells for us,” Tim Killian, a spokesman for Life Care, said of that time.

By the end of that week, health officials were monitoring 793 people whose recent travel history, or contact with an infected person, put them at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, state records show. Aside from Patient Zero’s close contacts, barely two dozen people in the state had met the CDC’s narrow criteria for testing. None tested positive for the virus.

Warning signals

Michelle Reid, superintendent of the Northshore School District, was at a Redmond elementary school event on a Tuesday night, Feb. 25, when she got an urgent text message.

Stepping out into a parking lot to return the call, one of her cabinet members filled her in: An employee of Bothell High School had traveled overseas with a family member, who later became ill; the family member was being tested for COVID-19. Reid consulted until midnight with staff and public-health experts, who assured her the risk of holding classes at Bothell was low.

Reid wasn’t so sure. She’d followed news that the virus had spread to Europe, and was concerned about the “fact pattern” she saw. The next day, shortly before 10 p.m., she made her call: Bothell High School became among the first in the nation to close due to concern over the coronavirus.

Public Health – Seattle & King County responded publicly that closing Bothell for deep cleaning was “not necessary from a public health point of view.”

As Reid’s action on Feb. 26 sparked new debate about the risk of the coronavirus, more troubling signs were emerging. A student at nearby Henry M. Jackson High School stayed home with a fever and body aches, went to a clinic and tested negative for flu.

The same day Reid decided to close Bothell High, two people who’d lived at Life Care died. The nursing home leaders decided they had to notify state health officials of the outbreak, and halted new admissions.

Still, staff members, residents and visiting guests gathered that afternoon for a belated Mardi Gras celebration, passing around plates of Cajun food, purple, green and gold hats and festive masks as a live band played.

A suspect emerges

“It’s going to disappear,” President Trump said of COVID-19 at a Feb. 27 briefing.

No new local coronavirus cases had been found in the state in the past month. Public Health – Seattle & King County had said consistently the virus posed little risk to the general public. Its posture began to change with two phone calls on Feb. 27.

The first was a voicemail from Life Care, reporting “increased numbers” of residents with respiratory illness, according to PHSKC. This wasn’t unusual for the flu season and wouldn’t have attracted much notice but for a second call that day, from EvergreenHealth.

Meagan Kay, an epidemiologist at PHSKC, listened with alarm as Evergreen staffers described two cases of unexplained pneumonia — one of whom had come from Life Care. The call coincided with a change in CDC’s criteria that would allow testing of patients without recent travel to China.

PHSKC sent a staffer to Evergreen to pick up the samples from the two patients and hand-deliver them to the state health lab in Shoreline.

As the doctors and public-health officials zeroed in on a link to Life Care, Doug Briggs was having trouble getting through to his mother, Barbara Dreyfuss, a resident of the nursing home. He thought the 75-year-old Brooklyn native might need help turning up the volume on her cellphone, so he stopped by around 2:30 p.m.

Briggs found his mother in her room, struggling to breathe. Staffers were setting up a portable X-ray machine to check for fluid in her lungs. Within three hours, she, too, was taken to EvergreenHealth.

While PHSKC officials waited for the test results, their counterparts in Snohomish County got more unsettling news. The directors of the Seattle Flu Study, a partnership with Seattle Children’s Hospital and other local institutions, had decided to test samples for COVID-19 without federal authorization and got a positive hit: the student at Jackson High School. The researchers immediately notified Children’s and public-health officials, who contacted the student’s family.

The teen, who had been feeling better, had returned to school that day. He’d been at Jackson for about five minutes when “he received a call to come home immediately,” according to the Snohomish Health District. A sample from the teen was sent to the state lab in Shoreline to confirm the result.

By that evening, the lab had results for four patients, including a Life Care employee. All tested positive for COVID-19.

The next day, Feb. 29, came news of the first death due to COVID-19. Gov. Jay Inslee declared a state of emergency. Even then, public-health officials said there was no reason for panic.

“The general American public is unlikely to be exposed to the virus that causes COVID-19 at this time, so the immediate health risk from COVID-19 is considered low,” the state Health Department’s website stated on March 2.

This was no comfort for Doug Briggs and his family. It had been only a week since he visited his mother at Life Care. They’d chatted about the restaurants they wanted to try as she sipped on a diet root beer.

On March 1, he donned a protective gown, gloves and a helmet as he sat by his mother’s side at Evergreen, playing songs by The Beatles and Barbra Streisand on his cellphone. Barbara Dreyfuss died somewhere between “Stand by Me” and “Here, There and Everywhere.”

She is one of 167 cases and 37 deaths, linked to Life Care — the highest toll associated with a single place in the nation.

Briggs and his wife have mourned in isolation.

“The one thing that has gotten to me, especially now that everyone is on lockdown, is the no grieving, no being able to hug somebody,” he said.

Falling short

Soon after the disclosure of the outbreak at Life Care, a retired Kirkland resident named Jim Hutchinson noticed that N95 masks — which he’d been using for a home remodeling project — were gone from the shelves of the local Home Depot.

Hutchinson knew more than most what this meant. Before he retired in late 2016, his job was to plan for catastrophic disasters for Washington state’s Emergency Management Division. He figured that the run on medical supplies had begun. He was right.

Washington state made its first request to the federal stockpile on Feb. 29, and within a few days got a delivery of respirators, surgical masks, gowns and gloves — fulfilling only part of the request. At 9:45 p.m. on March 3, Casey Katims, Gov. Inslee’s federal-government liaison, appealed to Washington state’s congressional delegation for help.

“The requests we’re receiving from local health jurisdictions are exceeding what we have available and we are now being forced to prioritize these requests based on the greatest need,” he emailed.

A second shipment from the stockpile arrived on March 12 with a large order placed by the University of Washington. But the truck carrying the supplies didn’t deliver to the UW “because the cargo was needed to fill higher priority needs” at the state Department of Social and Health Services.

Washington state officials requested 1,000 ventilators from the federal stockpile and had received 500 as of last week, according to email correspondence and state officials.

On March 15, a state Health Department employee sent a mass email directed to first responders and hospitals about its efforts to procure medical supplies and protective gear. By this point, the state had received hundreds of requests and managed to fulfill barely 7% of them.

“We will not be able to meet the full need in our state,” the email said. “All indicators show that the health of our supply chain is exceptionally limited and will worsen over time.”

“It’s important to recognize that global supply chains have been interrupted since the COVID-19 outbreak began,” the state’s Joint Information Center said in a statement. In addition to the surge in cases, “panic buying, and supply hoarding have led to shortages in PPE.”

The shortages extended beyond masks and hand sanitizer. For years, the Department of Health had received only a small fraction of the funding it had sought for public health, and soon the state Military Department began receiving all manner of requests for resources: epidemiologists, call-center support and quarantine facilities.

Public Health – Seattle & King County’s budget for responding to emergencies is $2.1 million, 77% less than it was a decade ago. The joint city-county health agency responded to the outbreak by reassigning employees, turning to private-sector medical professionals and enlisting more than 300 volunteers while training many on the fly.

Through late March, no other entity had requested more resources from the state, according to a Times analysis of requests logged by the Washington state Military Department.

PHSKC has hired a dozen temporary nursing staffers, requested laptops for new staff and software to schedule isolation space and run a call center remotely. “Starting from this far behind has meant that it’s much harder to quickly ramp up,” said Kate Cole, a spokeswoman.

“Empty”

On Sunday, March 8, the day after more than 33,000 fans turned out for a Sounders home game, the top elected leaders in Western Washington huddled in a King County office building.

Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan and King County Executive Dow Constantine sat at either end of a long table set with two jugs of Starbucks coffee, bags of dried fruit and nuts, and a bowl of tangerines. Gov. Jay Inslee sat in the middle. Some 20 others crowded into the room, without regard for the social distancing that would soon become their mantra.

State health officials gave a PowerPoint presentation that set the tone. Without aggressive action, there could be 2,000 COVID-19 cases, and as many as 5,000, in a week. Trend lines pointed straight up.

They debated the scope of a ban on crowds, batting around numbers from 50 to 1,000, ultimately setting on a cap of 250 people. At the time it felt radical. “We certainly were not at the point where people were talking about banning all public gatherings, which is a constitutionally guaranteed right,” Constantine said.

The next Sunday, March 15, David Postman, Inslee’s chief of staff, woke up to a flurry of phone calls from colleagues. Seattle’s bars were packed last night, and emergency room visits had spiked, he was told.

That evening, Inslee announced he would shut down restaurants and bars statewide and place limits on virtually all public gatherings.

At 10:40 p.m. on March 18, a state logistics official sent out an email to colleagues. An hour earlier, a team had finished scouring the state’s Thurston County warehouse for protective gear.

“We have done everything humanly possible to distribute every piece of PPE in the warehouse,” the official wrote. All that remained were some crates of masks that were useless against COVID-19, and cases of hand sanitizer earmarked for state emergency operations.

With those exceptions, he wrote, the “warehouse is empty.”

Hospitals have asked the public to sew masks. Inslee has pleaded with private manufacturers to abandon their business and produce masks, face shields and testing materials.

As Dr. Scott Lindquist looks back on the past three months, the state’s epidemiologist can find hardly any fault with the state’s response. “I think everyone did awesomely with what they had,” although earlier testing would have helped recognize the virus’ spread.

Only one thing has been difficult for him to swallow. “I find it hard that a country like the United States cannot have enough masks for its health-care providers,” he said. “I would not have thought that.”

Staff reporters Mary Hudetz, Sydney Brownstone, Manuel Villa, Dahlia Bazzaz, Patrick Malone, Ryan Blethen, Joseph O’Sullivan, Asia Fields and Jayda Evans contributed to this story.