Perhaps the defining image of Homeland, one of the most ambitious US drama series of the past decade, is Claire Danes’s character, Carrie Mathison, a mercurial CIA officer, staring at a video screen and displaying a sixth sense for the vital clue. So it is fitting that Danes appears to this interviewer not in person but via FaceTime.

“Let me just get on to my wifi,” she says, as the signal flickers, “I thought I was. OK, that should be better.”

Danes and her husband, the British actor Hugh Dancy, who have two sons – a seven-year-old and an 18-month-old – are weathering the coronavirus storm at a country house two hours north of New York, by far the worst-hit US city. “We’re just kind of acclimatising to this crazy new reality where we FaceTime all the time with everybody.”

And like millions of other parents, the 40-year-old actor is suddenly dealing with the challenge of home-schooling. “It’s full-on but I’m trying to download math apps and order a bunch of workbooks and stuff from Amazon, hoping that’ll keep them engaged.”

When the crisis erupted and brought daily life shuddering to a standstill, Danes had been enjoying her first few days back in “civilian” life after a blitz of media interviews to mark the end of Homeland after eight seasons, 96 episodes and five Golden Globe awards. She had been looking forward to catching some theatre.

In contrast with other art forms, pre-recorded television is immune to the virus (“It’s a resilient medium, it turns out”), and Homeland’s last bow may get a ratings boost from a captive audience. They will be witnessing the end of a landmark of 21st-century television, a drama set in the world of espionage and counterterrorism that has thrilled, surprised, frustrated, courted controversy, disappointed and returned to form, swung between sublime and ridiculous and, above all, never been less than relevant.

It is striking now that Homeland is often described as the first true post-9/11 drama when, in fact, it was born a full decade after the 11 September attacks on New York and Washington in 2001. Perhaps events of such magnitude take that long to sink in, and we will have to wait 10 years for similarly rich drama reflecting the age of Donald Trump and the coronavirus.

Created by Alex Gansa and Howard Gordon of 24 fame, Homeland never had the more writerly aspirations of Breaking Bad, Mad Men, The Sopranos or The Wire. But it was always contemporary, urgent, looking outward and thinking big. It captured many Americans’ ambivalence about the “war on terror” and their role in the world and showed tremendous capacity for reinvention.

“It’s a little like origami,” says Danes. “You just refold it and it becomes a slightly different creature. Its function was to mirror what was happening in the world and that’s ever changing, so by definition it had places to move and grow, and it was never going to suffer too badly from stagnation. My character was so wildly dynamic there was always a new facet to start to explore.”

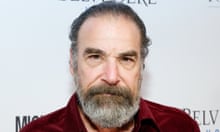

At its heart was a compelling relationship not, as first expected, between Mathison, a brilliant rule-breaker whose mind moves like jazz, and Nicholas Brody (Damian Lewis), a prisoner of war suspected of treason, but between Mathison and Saul Berenson (Mandy Patinkin), who emerges as her mentor and father figure.

“I think that’s a wonderful and surprising love story,” Danes reflects. “It’s not one that we see depicted all that often in pop culture: mentor and mentee.”

The rapport with Patinkin was mirrored off screen “kind of from the word go”, Danes says. “In our first read-through the chemistry was really powerful and palpable. He looks uncannily like my best friend’s dad, who kind of raised me and is a wonderful person but, if [he] got mad at you, you felt pretty shitty. I think that helped: very strong Pavlovian response already built in! And he’s [Patinkin] just very good at what he does. Our partnership grew and deepened over time.”

When Danes and Patinkin filmed their final scene together, the end of Homeland truly sank in. She recalls: “It’s not a casual scene. I think for me that was my cathartic moment when I realised it was over, because to say goodbye to it in its entirety is just too abstract and too huge. There were some tears – many of them – and we just hugged each other for a really long time.”

Danes was born in New York to artistic parents – a photographer and painter – and began learning modern dance when she was four years old. She was studying acting and performing on stage and screen by the age of 10, and landed her breakthrough role in My So-Called Life at 14, which took her to Los Angeles. She starred opposite Leonardo DiCaprio in Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 Romeo + Juliet before studying for two years at Yale University.

Her bohemian upbringing was not obvious preparation for playing a cog in the wheel of the national security apparatus and, at times, an agent of American imperialism.

“I grew up in downtown New York, surrounded by artists and deeply liberal folks who had a lot of scepticism about these organisations and institutions,” she says. “When you’re suddenly playing somebody who is in that world you can’t help but be moved by their efforts. I was really struck by their patriotism, that people make profound sacrifices on behalf of our country. I took that very seriously.”

Adapted for the US Showtime network from Gideon Raff’s Israeli series Prisoners of War, Homeland exploded into life in 2011, when water-cooler television was still a thing and a company called Netflix was working on its first original programme, House of Cards. Presumed dead, US marine sergeant Brody turns out to have been held as a prisoner of war by al-Qaida for eight years. He returns to America and a hero’s welcome. But CIA officer Mathison can see something no else does: that Brody has been turned and is now a double agent poised to attack America. She sounds the alarm but is not believed – in part, because of her bipolar disorder. And then she and Brody have a fling.

The first series dazzled critics, gained fans including Barack Obama and won Emmy awards for best lead actress, lead actor, drama series and writing for drama series. Season two maintained the momentum, including an audacious, much-praised episode in which Mathison interrogates Brody at great length.

But in a recent Los Angeles Times interview, Gansa said “it became much more difficult to write the show” after that episode. A subplot in which Brody again becomes a double agent was “strained”. The series indulged twists and turns that stretched credulity, and was in danger of “jumping the shark”. “Where Did Homeland Go Wrong?” demanded the New Yorker magazine.

The radical solution, apparently against Showtime’s wishes, was amputation: Brody was killed off, publicly hanged from a crane in Tehran as punishment for killing the head of Iranian intelligence, with Mathison watching in horror.

It was a chance for Homeland to start over. The team began attending an annual “spy camp” at the City Tavern Club in Georgetown, Washington DC, absorbing the accumulated insights and knowledge of current and former intelligence agents, diplomatic old hands and, one year, National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Speaking by phone, one of the participants in these brainstorming events, Michael Hayden, former director of the CIA and NSA, recalls: “A lot of times it was, ‘OK, what’s happening now?’ We talked about that and then they talked about whichever plot they were thinking about. It was a conversation. We then went to dinner and talked about it again. It’s interesting, because the more we did it, the more they had our kind of questions.”

Danes has fond memories of the spy camps. “The days were long and dense,” she says. “We’d meet at nine and the revolving door was in constant motion, depositing one story and then another, and they were often told by people who had very different ideologies and political positions. It was a huge privilege because you really did get to look into a crystal ball from all these amazing sources and get a fairly clear picture of what our reality might be like in a year’s time.”

Were there any surprises? “When we first started the show, I didn’t realise that Russians were a potentially difficult relationship. I thought we had worked through that! It’s also just a shock that these people actually exist. I was interested in how that would inform a person’s emotional makeup or their intimate relationships. You hear stories of people working [together] in really volatile posts for years on end and then they come home and separate: the adrenaline is gone. What it is to be so isolated, to carry all of those secrets, be shape-shifting, assuming different identities…”

This brains trust helped Homeland take a new, more self-questioning direction. The first episode of season four was entitled “The Drone Queen”, with Mathison in Kabul, Afghanistan, as the CIA’s youngest ever station chief. She gives the go-ahead for a military strike on a wedding in Pakistan, killing dozens of innocent civilians.

Season five shifted to Berlin, with Mathison having quit the CIA to work for a German billionaire philanthropist who, at one point, upbraids Berenson: “Nothing has made the world more dangerous than the foreign policy of the United States.” The series also kept bumping up against real events. The crew was filming in Berlin just after the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris.

Season six (early 2017) was even more spookily prescient on themes of fake news, Russian election interference and a president-elect at loggerheads with the intelligence community. It premiered five days before the inauguration of Trump, whose bellicose attacks on the FBI, CIA and so-called “deep state” appalled Danes.

“We worked with the intelligence community over the years, and I’ve been playing somebody within it. It was hard not to feel real empathy and deep appreciation and loyalty. So when suddenly they were dismissed and undermined by a president, it was just so hard to believe.”

The final season has again given a voice to outside critics of American adventurism abroad, and again mirrored real events, this time with a president winding down the country’s longest war, in Afghanistan. While there, Mathison is confronted by multiple gravestones bearing the same date of death, the consequence of her own past actions. And she comes full circle to find herself in Brody’s shoes, under suspicion for possibly having been turned by a foreign adversary.

Homeland’s politics remains complex and problematic. Some argue that, in the later years, it sought redemption. Did Danes observe a conscious tilt to the left? “I don’t know if we were editorialising too much,” she says. “I think we were really just charting that curve. Our [America’s] response to 9/11 was not great. We didn’t identify the real source of danger and conflict and we were too reactionary and we betrayed a lot of our values because of the panic we were in.

“So we kind of learned that as we went along. When I was talking to Alex [Gansa] about the final season, he framed it in a way that was helpful. He said when we first started telling our story, it was directly to do with our response to 9/11, and nearly a decade later we’re wondering if we’ve in fact learned anything, if we would react differently.

“He simulated an event that would sort of be comparable in scale, as traumatising and as consequential, which is the president’s helicopter going down. That was a litmus test. How do our characters in this story interpret that? Do they pause and judiciously consider their next move or do they go straight into offensive mode, a fear-based mode?”

One of the most enduring criticisms of the series is its portrayal of Muslims. Under the headline “Homeland is the most bigoted show on television”, writer and film-maker Laura Durkay wrote in the Washington Post in 2014: “Since its first episode, Homeland has churned out Islamophobic stereotypes as if its writers were getting paid by the cliche.”

The following year, Arab graffiti artists who had been hired by the producers to add realism to the set of Syrian refugee camp wrote: “Homeland is racist.” No one noticed and translated it until the episode was broadcast. It was, one comedian observed, a major intelligence failure. Danes acknowledges: “That was a good stunt. All of our hats were off to them.”

On the broader issue, she says: “I get it. I think it’s tricky and kind of inherently problematic, right? There are a lot of brown people in our story who are doing really bad things, and there aren’t enough opportunities to create a more balanced portrait of that demographic. That was always going to be a point of vulnerability for us, but I also think that our heroes are really problematic and really flawed. We’re wrestling with some pretty challenging questions and ideas and those two sides of various arguments were personified by our characters.

“In most cases I think both characters were right. Our writers were fairly responsible about that, creating a real debate. In the first episode of this season we have the Palestinian politician who’s really challenging Saul and making credible, cogent points about the ways that America has failed. I was happy about that at least.”

Another sensitive area has been Homeland’s portrayal of bipolar disorder. But Danes received positive feedback from people with the disorder. “They’ve been mostly appreciative, which I feel great relief about and gratitude for. That condition is not dramatised all that often so I think any conversation that’s stimulated by it is welcome. I never wanted her being bipolar to be a gimmick or just a convenient plot device, and I tried to be as specific and informed as possible. It’s a really fascinating human condition. I developed such respect for people who work as diligently as they do to just make it through a day.”

Actors sometimes talk about taking a while to shake off their last part, as if the character lingers like a ghost. Will Danes, who is now thinking about originating her own material, miss Carrie Mathison? “Oh my gosh, so much,” she says via the FaceTime link, where there will be no farewell handshake. “I loved her. It was just so nice to play the smartest person in the room, somebody who was so daring and unapologetically ambitious and such a badass. She’s not really going away.”

Homeland season eight screens on Channel 4 at 9pm (UK) and at 9pm on Showtime in the US. The entire series concludes on 26 April (US) and 3 May (UK)