In what may, at first, seem like an unimportant piece of computer geekery, Apple announced on June 22, 2020 that they would transition the Mac from Intel’s x86 processor lineup to custom chips they are calling Apple Silicon. This is huge news for the many photographers who rely on Macs for our work, and it is not clear at first whether it is good, bad or indifferent. The answer is almost certainly “some of all of the above”. To give a sense of how rare a transition like this is, there have been five prior transitions on a similar scale in the modern history of personal computing. It’s worth going through their history, simply to show the scale and potential disruption of what Apple just did.

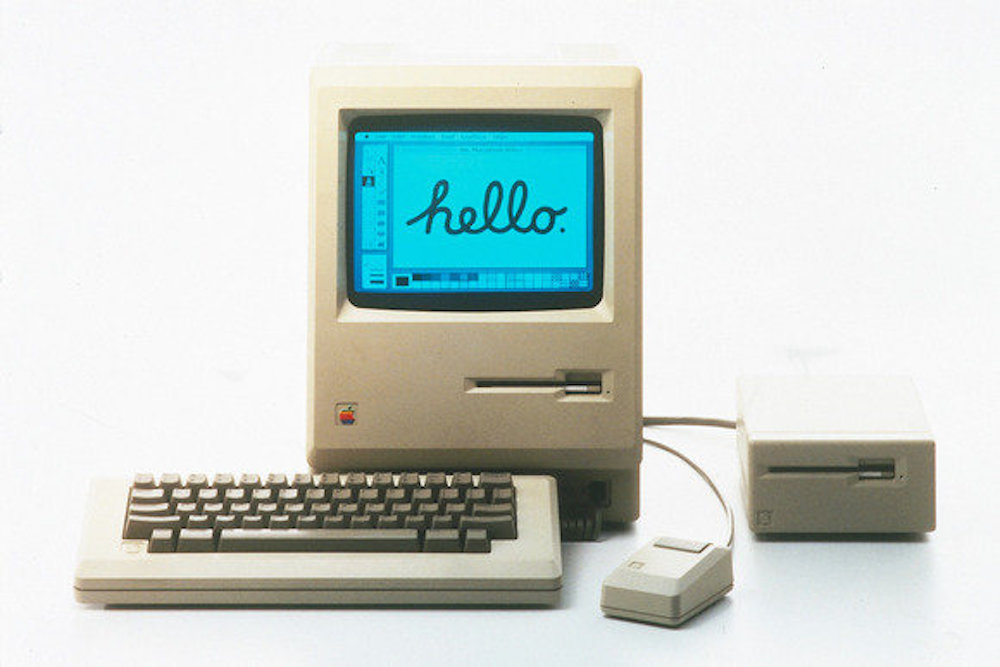

A Mac 128K – the first computer easily available to the public to use a mouse and menus. All the Macs in the trip down Mac memory lane are models I’ve owned and known well (although only the MacBook Pro is actually a picture of my machine).

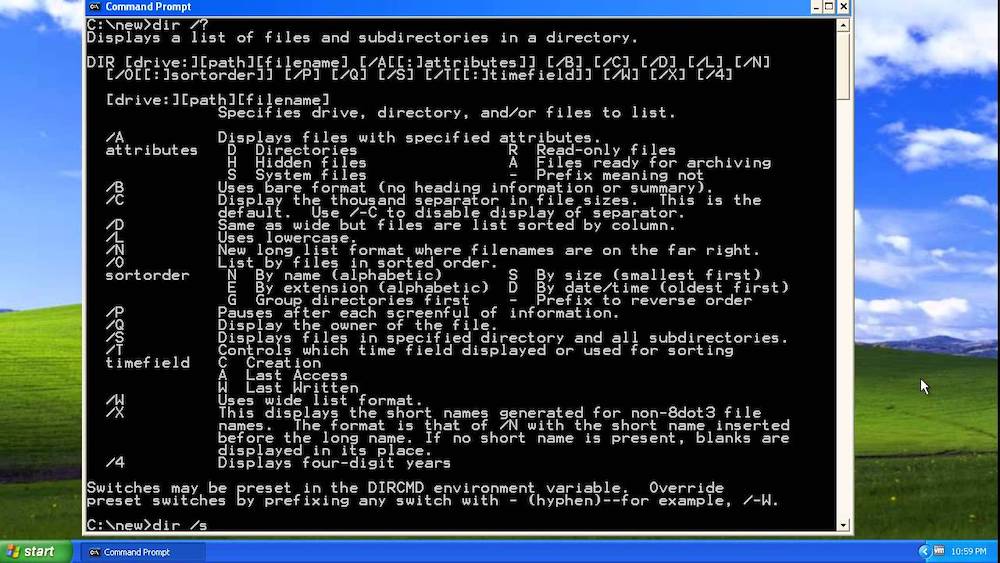

I’m defining “modern” personal computing as since the Mac came out in 1984, since the Mac was the first widely available computer with such things as on-screen fonts, a mouse and application windows. Before 1984, computers and users interacted through arcane codes. If you still remember what all three of ps -eaf, dir c:\files -p -w and shift-f7 did (they’re on three different machines – one is Unix, another is MS-DOS, and the third is WordPerfect running under DOS), but all were common in the 1980s), you’ve been using computers for a very long time. Bonus points for any reasonable description of the use of grep when searching man pages… All that changed in 1984, although it took a decade or so for essentially all computers to work like Macs.

Since that time, MS-DOS and Windows have undergone two major transitions, and the Mac has undergone three. Windows, amazingly, is still using the same underlying processor architecture DOS started with in 1982 – an Intel Core i9-10900K is a great, great,etc… grandchild architecture of the Intel 8088. You could run old DOS code on the modern Core-i9 if you could find an operating system that would let you, and it is actually possible with a (rare) 32-bit version of Windows, or with a small emulator in 64-bit Windows. There have been versions of Windows for other processor architectures, including ARM-based architectures similar to where Apple is going, but none have really caught on – for the vast majority of uses, Windows means Wintel (Windows on Intel), or on closely compatible AMD Ryzen chips.

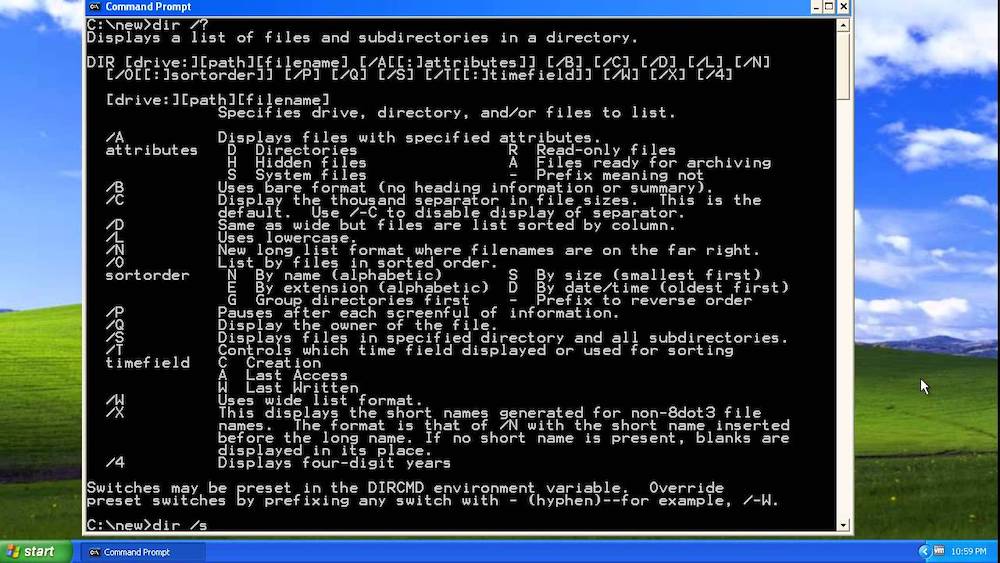

Even after Windows was no longer based on MS-DOS, you could still bring up a DOS prompt – here in Windows XP.

The first great transition on the Windows side was from DOS to Windows in the early 1990s. While Windows technically came out in 1985, very few people used Windows 1.0 or 2.0, and those who did either used Windows mainly as a file manager, or to run a single application. PageMaker required Windows long before Windows 3.0 came out in 1990, and it came with a run-time version of Windows that only ran PageMaker. Some people also used Windows 1.0 or 2.0 as a replacement for the DOS directory commands in copying and keeping track of files – there were many file management utilities at the time, and Windows was largely seen as one of them. In 1990, Windows 3.0 was the first version that many people used most of the time. Windows 3.1 and Windows for Workgroups increased the number of Windows, as opposed to DOS users further over the next few years, and, by 1995 and Windows 95, a PC was really a “Windows PC”, not a DOS PC. For some years afterwards, various utilities had to run in DOS, including, to Mac users’ great amusement, parts of the Windows installer.

Until 2000, consumer versions of Windows were shells running on top of DOS. Windows 95 was a highly sophisticated operating environment, with enormous extensions that DOS could never imagine – but DOS was still under it all. Windows NT, in use mainly in businesses, was a real operating system, not based on DOS. Microsoft had hired many of the software architects who wrote VMS for DEC’s VAX minicomputers, and they had written a new, much more stable Windows that eschewed DOS and shared some of VMS’ features. Early versions of Windows NT wouldn’t run a great deal of consumer Windows software, and they worked only with limited lists of peripherals – businesses were willing to deal with the limitations for the stability, but most consumers were not.

In late 2000, Microsoft released Windows 2000, which radically improved NT’s compatibility with both hardware and software. It still wouldn’t run most games, the majority of which were directly or indirectly dependent on DOS, but it ran most other software, and it worked with most peripherals. In 2003, Microsoft released Windows XP, which brought the remaining software, including games, to a modern, NT-based version of Windows. Ironically, XP was actually much less stable than Windows 2000 at first, and required a number of service packs before it caught up to its predecessor.

Early Windows XP was where much of Windows’ reputation for viruses and instability came from – when Microsoft added more game support to the very stable Windows 2000, they inadvertently added bugs that viruses could exploit as well. The huge variety of possible software and hardware configurations certainly didn’t help, especially when some of them were very low-quality and others were unstable gaming configurations – a problem Windows still faces, although it is getting much better. By about 2004, most Windows users were running some version of NT-based Windows, and that’s essentially what we have today – all supported versions of Windows are NT, although you occasionally run into old DOS-based Windows in an ATM, in a voting machine (frighteningly), in a scientific instrument or in some other odd embedded application.

On the Mac side, early Macs used Motorola’s 68×00-series processors, a competitor to Intel’s 80×86 series. It was a good choice at first – the 68000 was a significantly more capable processor than the 8086, and the 68020 and 68030 were significantly more capable than Intel’s 80286 and 80386. Combined with Apple’s more sophisticated operating system, there was the spectacle of a Mac IIci (released in 1989) running something that was recognizably Photoshop (released in early 1990) in 32 MB of RAM, while DOS users were struggling along with 640K memory limits and WordPerfect’s arcane function keys. In many ways, the Mac IIci was the first truly modern personal computer. It could be had (for a price) with a 24-bit HD display that put everything else short of Silicon Graphics workstations to shame. The one I had in college was still the best computer for its time that I have ever owned – it ran like it was imported from the future compared to contemporary systems, and it did a shocking percentage of what 2020 computers do…

By the early 1990s, however, there was a serious problem with continuing to rely on the 680×0 processors – while the 68040 was a nice chip, Intel’s 80486 could be clocked significantly higher. While a 40 MHz 68040 was actually faster than a 40 MHz 80486, 66, 75, 90 and 100 MHz ‘486 systems were showing up, and they were quite a bit faster than anything Apple had. They still lacked the elegance of a Mac – pre-95 versions of Windows were notoriously clunky, and limited to 256 colors (a huge limit for photography) – but their pure processing muscle was much greater than any Mac’s. Apple responded by transitioning the Mac from the 680×0 chips to Motorola and IBM’s PowerPC chips, which were much faster than the 680×0 line. As a matter of fact, the PowerPC chips were fast enough that they could emulate a 680×0 nearly as fast as the real thing could run. Disappointingly, software moved over to the PowerPC very slowly, so that, for the first several years of the new chips, most software (including parts of the operating system) was running in emulation – the performance gains of PowerPC took quite a while to manifest.

A few years later, shortly after the PowerPC transition was really paying off, Apple moved from the “classic” Mac OS to Mac OS X. Again, the early months and years were tricky, but the transition paid off in the end. Classic Mac OS was a series of bolted-on upgrades to an operating system first developed for a computer released in 1984, with a tiny black and white screen, an 8 MHz CPU, no hard drive and 128K of RAM. By the end of the road in the early 2000s, it was running on machines well over 1000 times as powerful, with up to 30” displays, gigabytes of RAM and hundreds of gigabytes of drive space. The limitations were becoming obvious, and Apple sorely needed a modern operating system. Apple bought NeXT, a company founded by Apple cofounder Steve Jobs after he left Apple, in the winter of 1996 and 1997. NeXT had two assets of interest to Apple – a wonderfully modern, UNIX-based operating system called NeXTSTEP and Steve Jobs himself. NeXTSTEP went on to become Mac OS X, first released in 2000, and the only supported Mac operating system by 2004 or so. Jobs, of course, went on to turn Apple into one of the most iconic companies in the world.

Shortly after Mac OS X was fully established, development slowed on the PowerPC microprocessors Macs of the time depended on. Fortunately, NeXTSTEP had long run on standard Intel-based PC hardware, and Apple had secretly continued to develop Mac OS X on Intel in parallel with PowerPC. In early 2006, Apple released the first Macs that ran Intel CPUs, and within a couple of years, Intel Macs running Mac OS X had become the standard, which they remained until June, 2020. To give a sense of how rare a transition of this magnitude is, we haven’t seen one anywhere in the computer industry since the Intel Mac transition in 2006-2008. Once Windows moved to NT, which was almost entirely completed around 2004, and the Mac was Intel-based, there has been neither a major processor architecture nor operating system transition. Apple tends to have an easier time with these transitions than Microsoft does – they control both the hardware and the software, and they often tend to have the next version running years ahead of when they need it. When they bought NeXTSTEP and turned it into Mac OS X, it already ran on standard Intel PC hardware – they kept developing that capability in parallel with PowerPC until they made the Intel transition five years later. They haven’t said so publicly, but current versions of Mac OS X are known to share quite a bit with iOS, and the new Apple Silicon processors in upcoming Macs will be closely related to the A-series chips in the iPhone and iPad – this version of Mac OS X is almost certainly something they’ve been working on for quite a while. All it would take is maintaining the additional pieces of Mac OS interface code that iOS doesn’t need. Even with Apple’s skill at transitions, there are major potential pitfalls here. There are also major advantages – Intel appears to have hit a wall where each succeeding version of their processors is only a few percent faster than its predecessor, while Apple is making performance gains of 30-50% annually with the A-series. A Mac with an A-series like processor will also run iPad and iPhone software natively, in addition to Mac software, but it won’t run Windows software in any easy way – no more Parallels, VMWare or Boot Camp. Those programs all depend on the Mac being, in effect, a PC. It is very possible that there will be more complex programs that permit some form of PC compatibility, by emulating the whole system. It will almost certainly be slower, though.

The big gain will probably be in efficiency – Apple’s A-series processors are much faster per watt than anything Intel makes. An iPad Pro and a MacBook Air are similar in computing power, but the iPad draws substantially less power, which allows it to be smaller, lighter and last longer on a charge. Nobody has ever built an A-series processor that draws 45 watts, much less 100 watts, unless Apple has one in a lab somewhere… Will the efficiency gains hold at higher powers? Will the A-series design even hold up at higher powers? Apple has a heck of a processor in the 2-5 watt range, but will it scale? There are two different ways they could try to scale it to MacBook Pros, iMacs and Mac Pros. First, they could just use a lot of the “high-power” cores from the iPhone or iPad– a chip with 10,12 or even 16 of the “Lightning” cores that the latest iPhones use two of should fit in a 16” MacBook Pro power envelope. A high-end iMac might use something like 32 cores, and a Mac Pro 64 or even 128 cores. The advantage of using a lot of iPhone or iPad cores is that much of the work is in designing the core – building a chip with more of the same cores is comparatively easy. The disadvantage is that some programs use a ton of cores more easily than others – developing for highly parallel systems (large numbers of cores) is hard.

Second, they could build a different core – a faster, more power-hungry version just for Macs. Apple already produces two related cores each year – the high-power and high-efficiency cores for the iPhone and iPad. Notebook and desktop computers probably won’t make much use of the high-efficiency core (although including a couple could be useful for things like checking e-mail while asleep) – the question is lots of the high-power core versus fewer of an “even higher power” core we haven’t seen yet. We presently know neither whether Apple CAN build that even higher power core, nor whether they are willing to invest in building it and updating it every year.

If the new Apple Silicon chips include higher powered cores substantially faster than anything we’ve seen in an iPhone or iPad, they could have a real speed advantage over Windows PCs for most tasks. The “Lightning” core used in the latest iPhones is already approaching the speed of a good Intel notebook core in bursts, and it shouldn’t be hard to use improved cooling to run it somewhat faster, and to let it sustain its speed for longer. Assuming that the reason Intel is struggling is their design and process, rather than some physical limit Apple will also hit when they try to go faster, Apple might be able to build something twice as fast as any Intel or AMD core – their architecture is much more streamlined.

Another question about hardware is what interfaces do and don’t continue on the new machines? USB 3 (or 4) in some form or another, probably a very fast variant, is definitely going to continue. I would expect Ethernet to remain on desktop machines, probably 10 Gigabit Ethernet across the high end, if not across the entire desktop line.

While a few articles have raised questions about Thunderbolt 3, which is partially an Intel standard, I’d strongly expect it to remain. Apple co-developed Thunderbolt with Intel, USB 4 includes Thunderbolt 3 in the standard, and, perhaps most significantly, Apple is very reliant on Thunderbolt. If you ask Apple “why can’t I upgrade the graphics in any Mac except the Mac Pro?”, they’ll say “use Thunderbolt”. If you ask them “how do I get more storage on my iMac or Macbook Pro”, their reply will be “Thunderbolt”. If you ask them about hooking up music interfaces or video switchers, they’ll answer “why, Thunderbolt, of course”. They aren’t going to give that up without providing another easy answer, and one that will let us keep using Thunderbolt 3 peripherals. There’s no other way of hooking up their fancy new display! it might be called USB 4, but the functionality of Thunderbolt 3 will be there.

Two interfaces I would worry about are old-style (non USB-C) USB and any display connector other than USB-C/Thunderbolt – both are gone on the notebook line, and persist on iMacs largely because they have gone so long without a redesign. Since the iMac is almost certain to get redesigned, both are probably gone (the one exception may be interfaces on Mac Pro GPUs). I’d expect the inconveniently placed SD slot on the iMac is also unlikely to remain.

What would it mean if Macs were twice as fast as comparable PCs, instead of only slightly faster? A Mac is a bit faster on average than a truly comparable Windows PC because Mac OS is more efficient than Windows for many tasks, but you can get Windows desktops with faster CPUs than any Mac, especially some of the newer AMD Ryzens. The new Apple Silicon could conceivably outrun Ryzens and Core i9s alike, and by a significant margin. Apple could have a big core nearing readiness that beats everything on the market on a core-for-core basis, and it could be much more power efficient than the competition as well. There were a couple of times in the PowerPC era when this was true, the last time Intel hit significant obstacles.

If Apple decides to go with lots of iPad-type cores, they may have a large theoretical speed advantage, but how practical will it be? Video editing tends to run very well on large numbers of cores, and Apple’s going to put a lot of effort into Final Cut Pro. A 16-core Apple Silicon MacBook Pro will probably be close to twice as capable in Final Cut as today’s 8-core Intel MBP. A 32-core iMac might outrun any vaguely standard desktop on the market today, including 28-core Mac Pros and even 32-core Threadrippers. A 64-core iMac Pro might be competing with small render farms and specialized multiprocessor systems costing tens of thousands of dollars. A 128-core Apple Silicon Mac Pro could easily outpace anything under $100,000.

Unfortunately, video editing using Apple’s own software is a best-case scenario. Many other applications don’t scale as well to multiple cores. Still photo editing ranges from nearly doubling in speed going from 8 to 16 similar cores to not being affected at all. The average speedup from doubling core count might be about 30-50%, but it varies enormously by task. On average, going from 8 to 16 cores gives a higher percentage speedup than 16 to 32, since the more cores you have, the harder it is for the developer to keep them all fed. Since desktop computers with more than 16 cores are vanishingly rare (a few Threadrippers and high-end Mac Pros), and desktop computers with more than 32 cores effectively don’t exist (a vanishingly small number of 64-core Threadrippers and 56-core Xeons, plus a tiny number of dual-processor workstations), few applications will be optimized for those core counts. Apple’s own software is likely to be one of the few exceptions, at least at first, if they go for a many-core strategy. It is worth remembering that it is only recently that Photoshop got good at using more than 4 cores.

There are three questions for photographers about whether this transition is good, bad or indifferent for us. The first is how well it runs older software. In both the 680×0 to PowerPC and PowerPC to Intel transitions, Apple provided emulators that allowed older software to run on the newer machines – but the performance losses to emulation were significant. In the transition from 680×0 to PowerPC, it took a couple of years before PowerPC machines were generally faster than 680×0 Macs in everyday use, because they spent so much of their time running in emulation. Late 68040-era Quadras (Quadrae?) were in significant demand for years after they were discontinued, due to software that was slow to make the transition (or never did). As late as 1997 or so, there were odd cases where a 1993-era Quadra 840AV still outran any other Mac, because of a piece of 680×0 software that lost so much performance to emulation that it ran faster native on the old Quadra than emulated on a much faster Power Mac.

The transition from PowerPC to Intel was much smoother, and it was more like a year and a half than three or four years that there were significant numbers of cases where the old machine was faster. In general, you could buy an Intel Mac and see a speed boost almost right away, and even straggler applications had caught up in the first year or year and a half. Adobe was widely considered very slow, and Intel-native Photoshop was out around a year after the first Intel Macs, and only six months after the Mac Pro replaced the Power Mac G5. A big part of this was that Mac OS X was immediately Intel-native, while much of Mac OS had been emulated in the early PowerPC era.

My expectation is that this transition will be more like PowerPC to Intel than 680×0 to PowerPC. Both Adobe and Microsoft, notorious stragglers, have announced that they are working on ARM-native software, and expect to have the native versions out relatively quickly. The operating system will be native immediately – Mac OS shares so much code with iOS that, similarly to Mac OS on Intel, which took advantage of the long-extant NeXTSTEP for Intel, it essentially already exists, and a fully native Mac OS (which they’re calling MacOS 11 Big Sur, finally leaving the Mac OS X version number) should ship alongside the first publicly available Apple Silicon Macs.

According to Apple, well-written Mac software should convert to Apple Silicon native essentially with a recompile – a matter of a few days of work, according to Apple. Such things never go as smoothly as they are claimed to, but if the work involved is weeks instead of months, we could see a lot of native software fairly quickly. There may be some applications that contain a lot of old code that is hard to convert – Photoshop was reputed for years to contain pieces of assembly language code that would have to be converted entirely by hand. I’m not sure whether it still does.

The second question is what kind of software we’ll see for the new Macs. Intel Macs are a great deal like PCs from a hardware perspective (they essentially ARE well-built PCs), which made Mac/Windows cross-platform software easier than when developers had to consider the idiosyncrasies of the PowerPC and varying amounts of Apple custom hardware. Some Mac/Windows cross-platform applications are very well ported to the Mac (or started out there), while others really look like they belong on Windows (I’m looking at you, Microsoft, as I stare at Word’s two menubars). Microsoft Office for the Mac is much larger on disk than Office for Windows, and it is thought to contain large pieces of Windows code – instead of porting at all, Microsoft may be running some parts of Windows that Office depends on. While some ports aren’t perfect, the similarities mean that we have access to a great deal of Windows-first software on the Mac, even without using Parallels, VMWare or Boot Camp. It’s easy for developers to release a Mac version, so many do.

Apple Silicon will move the Mac back to being significantly different from a Windows PC. At the same time, it will have major hardware similarities to an iPad. Apple claims, and I believe them, that iPad and iPhone software will run without modification on an Apple Silicon Mac – this would mean that Apple has to have a translation layer in the operating system to handle the interface differences, but that shouldn’t be terribly hard to do. In one sense, this is excellent – Macs will immediately gain camera remote and downloading apps from all major manufacturers, for example. Social networking applications like Instagram and WhatsApp will also immediately pick up Mac-native versions, since the iOS version works.

Where this is a challenge is in cases where porting the Windows version just got harder, but there is an iOS version to rely on. If the Mac, Windows and iOS versions are all at feature parity, that’s not a problem. If all three do the same thing, who cares which one the Mac version is related to? That’s for the developer to worry about, not the photographer. The concern comes in the case of feature-incomplete iOS versions. Many developers (including, but not limited to Microsoft and Adobe), have mobile versions of their applications that lack important features found in desktop versions (where’s the “print” command, Adobe?). Depending on how hard porting from Windows is, there may be a temptation to give Mac users the iOS version, or a slightly enhanced version of the iOS version, rather than the full desktop version. Microsoft Office will be interesting to watch, since it is put out by a very large company, and the iOS version is functional but lacks many desktop features. Of course, the big question for photographers here, and one I keep returning to, is the future of Lightroom Classic. During the Apple keynote where the new direction was presented, Apple showed off Lightroom CC, but specifically not Lightroom Classic. If Adobe is working on Apple Silicon by starting from the iOS code base and enhancing from there, Lightroom Classic is unlikely to ever be ported – there’s no iOS version, while Lightroom CC started life on iOS. If they’re porting the full desktop Creative Cloud, Lightroom Classic is a more likely possibility (but not guaranteed – Lightroom CC is easier to port, and it’s what Adobe is more interested in). There is an important advantage from Adobe’s perspective in starting with the iOS versions – they use more modern code. On the other hand, not everything exists on iOS – a number of the CC apps don’t have any mobile equivalent at all.

Might it be a combination – iOS-derived apps with feature enhancements in some cases, but with ports of desktop-only apps like InDesign? There will be Lightroom, but will there be Lightroom Classic with full native performance? I’d say flip a coin, or maybe a little more pessimistic than that, and we’ll know fairly soon after these machines reach consumers – if various other Adobe apps arrive, but the only Lightroom is CC, we’ll know that Classic will probably never be updated (if it were to be updated, it would probably be among the first Adobe apps). The arrival of a native Apple Silicon version would suggest another few years of support, since Adobe is unlikely to make the effort only to go CC exclusive a year or two later. In any case, Lightroom Classic should run as an emulated app for a while – it will be a high priority for Apple, because it is such an important piece of software. If it is emulated-only, that is a strong incentive to think about what’s next, because emulation layers don’t last forever.

One major advantage from a software viewpoint is that Apple Silicon Mac apps should take very little work to run on iPads. It might not be fully automatic, but it is likely to be close. This means that most raw converters and other photo editors that make the transition should exist for the iPad fairly quickly – a boon for editing in the field! If your favorite raw converter runs on the iPad Mini, which many of them should next year, a full-fledged field viewer and editor with an excellent screen, camera remote control, downloading and tethering weighs about 2/3 lb (300 g). Battery life will be a concern – good portable battery packs (I use and recommend the Zendure series) are a must if you aren’t near an outlet.

The third big question is what the hardware will be like? If Apple is building a new, higher performance core and Apple Silicon Macs retain similar core counts to present Macs, but with much higher per-core performance, it should be a major performance gain, and not too hard to optimize for. If Apple goes with large numbers of iPad-type cores, that may require a substantial amount of optimization to work well – and some processes will be tough or impossible to optimize. In any case, there will be quite a few new hardware features that have to be specifically coded for, even if the basic core design is easy to develop for. How many developers will use the new features, how well will they use them, and how fast will the new machines be with non-optimized software?

There will be three basic classes of software: Emulated, native (but non-optimized) and optimized. Emulated software will certainly be the slowest, and will probably be slower than the same application on a modern Intel Mac, at least in many cases. Depending on the actual performance of Apple’s new chips and on how much a given application uses operating system calls (native) versus its own code (emulated), there may be some cases where an emulated application is faster than the same application on a comparable Intel Mac, perhaps especially on very light MacBooks where Apple Silicon’s performance-per-watt advantage is greatest.

Native applications that have been recompiled to take advantage of the new chips, but not specifically optimized need to be faster than they would be on a comparable Intel Mac, and, unless Apple makes real mistakes, for the most part they will be. How much faster remains to be seen, and it will depend on specific design choices. Finally, highly optimized applications will be the fastest of all, but they will take significant work on developers’ part – how many will justify the effort?

How unusual the hardware design is compared to a standard PC will play a huge role in the need for optimization. A couple of things to watch are “normal” core counts (4 to 8 (maybe 12) in notebooks, 4 to 16 (maybe 32 in a high-end model) in desktops, up to 32 or even 64 in the Mac Pro) versus very large numbers of slower cores (a 16 or especially 32 core notebook, anything at all with >100 cores) and how much of the power of the design is locked up in things requiring specialized coding like the Neural Engine. A simple recompile isn’t going to optimize for 32 cores and half of the power in specialized coprocessors, but it very well might suffice for a very fast 8-core machine.

What does all of this mean for photographers? On the positive side, we can probably expect much better ultralight notebooks. This is where Apple has all the experience with the A-series chips, and there is little doubt that an A-series chip offers much better power per watt than anything Intel or AMD offers. Whether you prefer it with a touchscreen branded as an iPad, or with a built-in keyboard branded as a Mac, the machine that slips into a small pocket of your camera bag will benefit from the new chips, and from increased software interoperability. There will be a real advantage for Apple in this size range – enough that I wouldn’t buy any computer under 2.5 lbs (1.1 kg) until Apple’s shown their hand, unless you are a really dedicated PC user.

The existence of iPad and iPhone software on Macs is another solid advantage. Studio photographers in particular are going to love the wireless tether functionality they just picked up, courtesy of Nikon SnapBridge, Sony Imaging Edge, Fujifilm Cam Remote, etc. Social networking apps becoming native on Macs is another advantage for photographers who want to post edited images, images taken with a 600mm lens, or other things that the “snap and post from your phone” paradigm doesn’t really cover. There are many little utilities that I’ll be sitting in front of my Mac and reach for, only to remember “oh, that’s a darned phone app”. Hardware on larger laptops and desktops remains to be seen. It will almost certainly be highly capable with the right software, but how hard will it be to write that software for? It could be transparent for the user, and not too hard for the developer – or it could be a pain that requires significantly new software. It could be a minor speed gain, or it could be huge. Apple’s architecture could lead to repeated 30-50% annual speed gains while PCs only gain 5% each year – or it could hit a wall in a couple of years, just as Intel did a few years ago. Computer scientists are not sure whether Intel’s lack of performance gains these last few years is due to unique issues with Intel’s architecture, whether Intel is simply closer to a performance wall set by physics than other companies are, or a bit of both. If Apple gets significant performance gains that elude the rest of the industry that remains tied to Intel’s architecture out of this, it’s certainly worth the trouble.

The loss of easy cross-platform software with Windows is a disadvantage, and it could be a major disadvantage. When Apple moved to Intel, a lot of small, previously Windows-only developers ported their software to the Mac for the first time. Moving to Apple Silicon means giving at least some of that up, in return for easier compatibility with iPad and iPhone apps. Software has become much more abstract from hardware in the past 15 years, and it is possible that we’ll lose very little software that came from Windows. If Apple is right that it’s just a recompile for most software, then almost every developer should be willing to do that. If what Apple is leaving unsaid is that it’s just a recompile if your application is very well-behaved on the Mac, but it is much harder than that for applications ported from Windows or with a lot of old code, we could lose quite a bit.

In the end, this is a good thing for the Mac overall – those great, fast ultraportables are going to sell very well in education, where Macs are always strong. Is it good for the Mac in photography? Probably in the end, although how many rough spots there are remains to be seen. How does it fit our workflows as individual photographers? That depends on how well our software and peripherals work with the new Mac. It’s worth it when it makes our lives easier.

Dan Wells

June 2020

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

You May Also Enjoy...

Hand’s On: new Sony A9III and Sony 50mm G Master, Sony 85mm G Master, Sony 75-350mm APS lenses

A quick hands on look at Sony A9iii and the Sony APS 75-350mm len

The best wide-angle zoom in the world? The Fujinon G5 20-35mm f4 R WR reviewed.

FUJIFILM GF 20-35mm f/4 R WR L