Dennis Morris

‘I’ve taken a lot of flak. But, like the boy, you keep pedalling on’

I remember seeing this child in a playground. He looked so confident, like he was ready for the world. A young boy riding off into the unknown, the markings on the ground like latitude lines. I was once a little boy like that.

When I was leaving school, I wanted to be a photographer. My careers officer said: “Don’t be silly, Morris. There’s no such thing as a black photographer.” My parents said: “You heard what your careers officer said. Why don’t you get yourself a job as an electrician?” I said: “No, I want to be a photographer.”

I was getting flak from both white authority and my own community, but you have to be resilient. You have to use your mind and create. Like that boy on the tricycle, you have to keep forging ahead, keep pedalling regardless.

The demonstrations these last few months are fantastic but what people don’t seem to realise is it ain’t going to end tomorrow. It’s going to be a long, long struggle. I’ve been on many demonstrations. I’ve had my problems with the police. In my day, you didn’t have phones to take videos: you just got the shit beaten out of you, and that was it.

It took a lot of faith to really stand up and still walk on to the street and say that you’re still a part of England, or America, despite the way you were treated. Hope is not a word I’m into. For what we’re dealing with here, we need to have faith that it will change. I have faith. Interview by Dale Berning Sawa

CV

Born: Kingston, Jamaica, 1960.

Shot taken: 1976.

Trained: Under Donald Paterson, Royal Photographic Society fellow.

Top tip: Use your third eye.

Visit Dennis Morris’s website.

Othello De’Souza-Hartley

‘When I warned the miners I’d be nude, they said they used to shower with 500 men’

I took this self-portrait in the National Coal Mining Museum in Wakefield in 2014. I was working on a project about masculinity when I saw a documentary that got me thinking about industry. It featured a white working-class man sat in his kitchen, talking about how losing his job had made him feel demasculated. I decided to leave my comfort zone in London and speak to men in other parts of the country.

In Wakefield, Tyneside, Middlesbrough and across the Midlands, I interviewed ex-coal miners, men who worked in the shipping industry, others who worked for Tata Steel. The images I created in response were like performances: I was holding all of these stories in my mind as I posed. It was about breaking down toxic masculinity, and bringing out things that men don’t usually reveal.

I brought my own insecurities, too. I’m a black male, and some of the places I went to were predominantly white working class. Many people told me southerners don’t understand what it’s like in the north. And being an artist, I feared they might find it all pretentious.

The first thing I said to the men at the mine who were helping me was: “You know I’m getting nude for this?” They said: “Listen, we worked in a coal mine. There were 500 men going in the showers at the end of the day.” One said another documentary photographer had come to photograph the mines, but they said it felt like he had his agenda didn’t reflect how they felt. “But,” he said, “you getting naked is how I feel inside.”

Younger people in the area were facing joblessness, alcoholism or the break-up of their community through people leaving for the south. They wanted to be coal miners, not tour guides. It wasn’t just what they did – it was who they had been for generations. Doing the project in London, there was more talk about the self, but here the talk was about family and the community.

In one town, there was a poster in the pub for an English Defence League meeting, which is something you would never see in London. A Scottish friend I was with wanted to get out of there, but I thought it was good to experience that you can be in the same country yet in a place where you can put that on the door of a pub.

A Nigerian collector once told me he couldn’t look at this image. A black body, on the ground, in a dark space – it reminded him of slave ships. For me, though, the image is about how I found a middle ground with these men – who, on paper, I wouldn’t have had any connection to – talking about what it’s like to be a man today. DBS

CV

Born: London, 1977.

Shot taken: 2014.

Trained: Central St Martins (BA); Camberwell College of Arts (MA).

Top tip: Focus on your work. Enjoy the process of how it develops over time.

Visit Othello De’Souza-Hartley’s website.

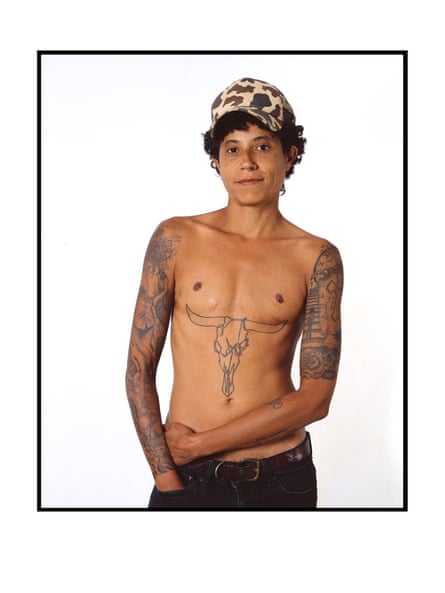

Lola Flash

‘The more change I see, the more I realise I have made an impact’

I met Utah at [New York gay bar] Stonewall. We might have both been on dates. We nodded at each other, in a brotherly way. And we kept in touch. I knew I wanted to take a portrait of them. They look quite similar to me – I am constantly misgendered: my hair is short, I wear masculine clothes. People often assume I’m a guy, so I’ve been working for a long time on a series of portraits of gender-fluid people.

Utah was living in the Bay Area. I said, “When you come back to New York, please come stay.” And they did. They were so cute. They just dropped their bags and they sat on the floor and were, like: “Tell me everything.”

I was part of [Aids activist group] Act Up back in the day. Utah wanted to know all about it, from the marches to the Kissing Doesn’t Kill poster I featured in – the one Gran Fury made in 1989. I’m quite modest, but the more I see change happening, the more I realise I have made an impact on our history. Back then, though, there was no basking in any kind of glory. We just did those things like do a photoshoot, then go to a funeral, then visit someone in the hospital. I’ve been thinking about the parallels between the Aids crisis and Covid-19: the triggering effect of all the deaths, the disproportionate numbers of black and brown people being affected.

In 1990, I came to London. I lived in a squat. I went to blues parties in dark basements, where black queer folk communed. I learned that UB40 wasn’t just a band: people would lend me their cards. And I marvelled at the unity on council estates. Back in the US, low-income housing is totally segregated, whereas here I had friends – white and black – whose families had been friends for generations. There were things in place here for low-income folks that made so much sense to me. Still today, even though I’ve been back in New York for 17 years, I’ll catch myself saying “home” when referring to England. DBS

CV

Born: New Jersey, 1959 (British and US citizenship).

Shot taken: 2018.

Trained: Maryland Institute College of Art; London College of Printing.

Top tip: Show the world how and what you see, and never hide the truth.

Jennie Baptiste

‘Pinky only wore pink. Her whole house was shades of pink too’

My first photographic foray into the world of dancehall, or ragga as it was called, was in 1994. I was intrigued by how strong the women were in terms of how they represented themselves.

I had heard about Pinky – she is well known. I was especially intrigued to learn that she only wore pink. We arranged to meet at her house in Brixton. I thought we’d probably shoot in the living room, which plays an important part in Caribbean culture – it’s where you get together.

Pinky came down the stairs with a huge pink suitcase. She opened it up on the living room floor and it was an abundance of pink. Her whole house, too, was full of different shades of pink.

My projects have always been based around black youth culture, my heritage and my identity. It was easier for me to depict something that I was familiar with. And at that time, we weren’t being represented in mainstream culture.

When I was 15 and said I wanted to do photography, my careers officer told me I couldn’t. I struggled with lecturers not getting where I was coming from. One of the responses I got to my work on ragga was: “This doesn’t mean anything – it’s throwaway culture.” How can you assess my work, I wondered, if you’re not even willing to understand the culture I’m a part of?

Of course, dancehall is now mainstream. And some of those pictures now are in the Victoria & Albert Museum. This image in particular has taken on a life of its own. It’s in the Black Cultural Archives too, a place that held great significance for me as a student. It is the only one of its kind in the UK. It has been around for almost 40 years, yet they still need support – it shouldn’t be that way. DBS

CV

Born: London, 1971.

Shot taken: 2002.

Trained: London College of Communication.

Top tip: Research other photographers’ work, and develop personal creative projects. If it’s a subject you’re passionate about, shoot it.

Visit Jennie Baptiste’s website.

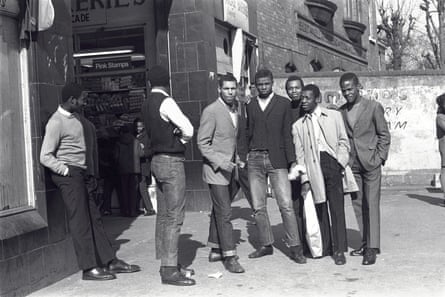

Neil Kenlock

‘We were trying to say: I am good, I am great, I have good shoes!’

You don’t see people dressing like this any more. I was with my friends – George, Bertie, Myrie, Danny da Costa, and a few guys who just stepped into the frame on Brixton market – sometime in 1977. I looked back at the group, and said: “Let’s have a picture!” I always had my camera with me at the time.

Walking around the market on a Saturday is what we always did. You had to have those particular shoes (American-style brogues) and trousers of that particular length, with the jacket. If you didn’t, you were nobody. If there was a particular function, and you didn’t come in a suit and tie, nobody wanted to talk to you. The good thing for me was that because I was the photographer, I could just walk around and they wouldn’t chastise me for not looking good. But style was something we always paid attention to.

Of course it was expensive. Depending on how much money you had, you would have the clothes made up for you. The whole idea was to dress up really nice, showing: “I am good, I am great, I have good shoes!” Looking back at the image now, I wish I’d removed that piece of litter on the ground. I didn’t think of it at the time.

I went to school with most of these men, and we’ve been friends ever since. Some of them joined the British Black Panther movement with me. It was about enlightenment and understanding ourselves and the community. Being the photographer, I had to document everything. If people wanted to come into the march and create problems, it was important to have cameras around – it was a kind of protection.

I was impressed with the recent Black Lives Matter walk. I did the whole thing, from Trafalgar Square all the way to Whitehall. I took a lot of photographs. It is very important to us, very important to a lot of people. DBS

CV

Born: Port Antonio, Jamaica, 1950.

Shot taken: 1975.

Trained: On the job at Montage.

Top tip: Focus on one topic and keep taking photos in that environment to become an expert. If you like music, for example, stay in that area.

Ingrid Pollard

‘People always expect my work to show angry black people shouting’

The picture is of Richelle. She’s a performer: a dancer, a drummer, a yoga life-coach. I used to work with her when she lived in London – this image was taken more than 20 years ago. She would dance to live poetry. It was very hard to take a bad picture of her. This, though, is a favourite for both of us.

There’s a number of things going on that I still take pleasure in. I like the textures – of her hair, her skin, the weight of her handmade jacket, the muscle formation of a dancer’s body. I love that triangle of light under her eye and how it lifts that darker area and gives it tone. Film – slide film in particular – was biased towards lighter skins, and gave very limited tonal range in darker areas and on darker skins. Pre-digital, you had to work really hard to bring out the range of skin tones. I love how the lighting falls on Richelle’s skin. It’s a picture about beauty, and it’s about confidence, and about the trust there was between us.

I’ve spent much of my 40-year photographic career trying to talk about performance as well as areas such as landscape and history, but I’ve found that the assumptions around what my practice is, and the issues I’m addressing mean it is always going to be about race. As a black person you are bracketed, allowed to address one thing and that’s race. Typically people look at my images and say: “What is this?” They expect to see images of angry black people shouting, alienated. It’s incredibly limiting.

Growing up, I always wanted to do something artistic, but I wasn’t encouraged to go to university – my teachers suggested I work in a shop. Today I have an MA and PhD in photography and film, but I am continually underestimated. Recently I’ve started feeling a bit more confident about calling people out on this. Things are changing slowly, but it’s a long game. Interview by Imogen Tilden

CV

Born: Guyana, 1953.

Shot taken: 2002.

Trained: London College of Printing (BA), Derby University (MA and Westminster University (PhD).

Top tip: It’s all about the light.

Visit Ingrid Pollard’s website.

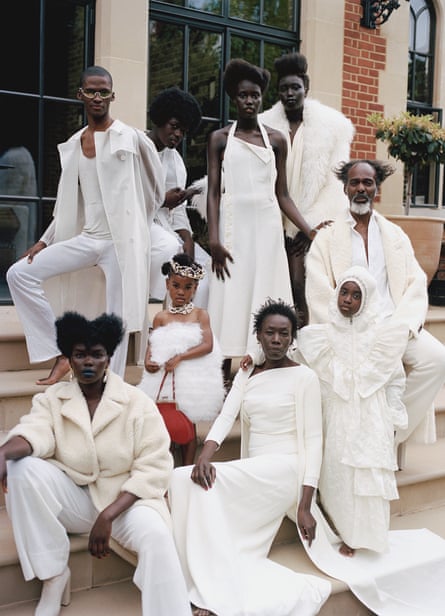

Ronan Mckenzie

‘I dressed them in white to suggest purity, innocence, a blank slate’

My images are about personality and character. I like to work with the energy of the people in front of me and see what they create. This was the last shot of the day, part of a series commissioned by Luncheon magazine for a story called Present Finally that featured images exploring the idea of black royalty. I hadn’t thought much about composition, other than seeing that the steps would work for the different levels. I placed the group, they moved around a little, and it just came together. Most of my work is quite spontaneous. I dressed everyone in white because it can mean so many things – it’s the colour of purity and innocence, a colour that signifies nature, freshness, a new beginning. Yet it’s also a blank slate.

I began my career taking lots of pictures of my mum and have continued to shoot her – I love to work with lots of different types of, and generations of, people. I love the bond there is between this group. You really feel the strength of each individual person – even the little girls. Anthony – the older guy – is one of the most elegant and lovely men I’ve ever met, there’s two sets of sisters in there and most of the group knew each other before the shoot. It feels like an image about community, about standing together, which is particularly appropriate for this present time.

It’s good that everyone is talking at the moment about the human injustice that is racism. Without us all understanding that something is wrong and needs to change things can’t move forward. But this is about more than having BAME authors in libraries or putting a black photographer behind the camera. It’s about changing people’s perspectives. Black image-makers need to be seen as image-makers and not as black-image makers. I’ve experienced so many micro-aggressions and come up against so much ignorance in the fashion and photo-making industry. Opportunities should be given on merit not on the basis of who you know. I need to be able to have the platforms to share the images I want to share. I want to say the things I want to say but I don’t want to have to wait 50 years for a show at Tate or the cover of Vogue to say it. IT

CV

Born: London, 1994.

Shot taken: 2019.

Trained: Self-taught – attended Central Saint Martins for one week and dropped out.

Top tip: Make sure all of your work is for you and comes from your heart.

Visit Ronan Mckenzie’s website.

Vanley Burke

‘The protesters’ banner says: If we must die, let it not be like hogs’

This shot was taken nearly 40 years ago at one of the many demonstrations that were taking place in Birmingham but it resonates with the times we’re going through right now. It’s a group of young people protesting about police harassment. They were on a march that started in Handsworth, which is where I still live, and ended at Steelhouse Lane police station. The banner says, “If we must die let it not be like hogs”, which is taken from a poem by US writer Claude McKay written in 1919 following attacks by white Americans on African Americans that sparked race riots.

At the time, I was seeing negative reports in the press about black people in the UK, and, in my work, I set about trying to redress this negativity. I wanted to tell a true story and reflect how things really were. A lady stopped me in the street and thanked me for my work. I said, “That’s very of nice of you” and moved on. But she grabbed me, looked me in the eye and said that without these photographs she wouldn’t have been able to tell her children about her past.

Britain is still an unequal society and I’m not sure anything will really change. A report will be written and filed away. We need to look inside – and that is what the country has failed to do. Whenever we talk about the British abroad, we constantly talk about how we “civilised” people. I mean, come on. Interview by Ryan Herman

CV

Born: St Thomas, Jamaica, 1951.

Shot taken: 1972.

Training: Self-taught.

Top tip: Get rid of your TV. Television is a seducer – it pulls you in when you should be outside taking photographs.

Visit Vanley Burke’s website.