There weren’t many options for women in music in 1974. Only three women – Diana Ross, Karen Carpenter and Lena Zavaroni – made it into the Top 10 of the UK album chart all year, and Broadway singer Bette Midler had just won best new artist at the Grammys. Female rock stars were starting to gain traction – Suzi Quatro was rising up the charts and the Runaways were waiting in the wings – but it was still years before female punk acts like X-Ray Spex and the Slits.

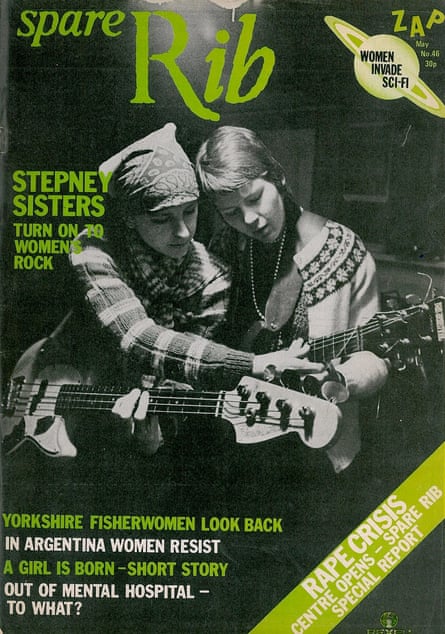

The Stepney Sisters, embedded in the Women’s Liberation Movement, took a completely new tack. Decked out in their band uniform of cropped haircuts and denim dungarees (a far cry from the leather and corsetry of the era’s female rockers), the group wrote politically charged pop-soul brimming with multi-part harmonies straight from the 60s girl group era. They were prolific composers and sticklers for equality, each member encouraged to express themselves through their songwriting.

Despite a sizeable catalogue of material, it’s only now – almost half a century on from forming – that this pioneering feminist group is releasing their debut record. But while the Stepney Sisters have been largely unknown in the interim, drummer Susy Hogarth argues that they helped move the dial for women in British music. “People involved in the feminist movement will have seen us,” she says. “We played to women up and down the country. That changed what happened next … it must have done.”

Singer Caroline Gilfillan, bassist Marion “Benni” Lees, and saxophonist Ruthie Smith were the original heart of the band, first performing together as a trio of singers in soul band Expensive while at York University. Their biggest gig came supporting the Wailers at Langwith College in 1973. “It was right at the beginning of their career before they became well known,” Smith explains. Lees continues: “They looked like fish out of water. Ultra-cool guys smoking these massive spliffs, dressed in this Rasta way which was a completely foreign world to us.” The trio impressed Bob Marley so much that he asked them to join the group, but they demurred to focus on their studies. “We can’t just up and leave, we’ve got three degrees to finish!” mimics Lees indignantly.

Expensive moved to London to scale up their ambitions, but the male band members soon became preoccupied with other ventures: bassist Steve Beresford went on to become a celebrated proponent of free improv, while John Telfer is now the Archers’ longstanding vicar, Rev Alan Franks. “I remember arranging a photo shoot and half the band didn’t turn up,” Lee says. “We had to get some strangers from the street to come and stand in the photo.”

Gilfillan recalls putting an advert in the local paper looking for band members. “I got a succession of unpleasant and abusive phone calls: ‘I can give you what you want, love’. And that was just the response to a small ad!”

These frustrations sparked their creative autonomy. “We were longing to play some music. It dawned on us that if we didn’t learn the instruments, you’d be for ever hanging around waiting to be asked,” Gilfillan says. The group was completed by guitarist Nony Ardill and keyboardist Sharon (Shaz) Nassauer. “We didn’t want to thrash around the lowest common denominator, playing three chords and singing out of tune,” Gilfillan continues. “We wanted to do stuff that was soulful, with thoughtful lyrics.”

Hogarth was already entrenched in the music scene, performing with the Resisters, a leftwing political proto-punk group, and politics would quickly inform the Sisters’ songwriting, providing a counter-narrative to current chart acts: Hall & Oates cooing over Sara’s Smile, and Dr Hook’s now questionable Only Sixteen. “The way we put ideas together wasn’t about the standard feminist thing,” Ardill says. “We had songs about a range of issues because we took our politics way beyond feminism.”

The band wanted to prove – per the rallying second-wave feminist slogan – that the personal was political. The Sixth Demand explored the women’s liberation movement’s call for “the right to a self-defined sexuality”; Surgery Blues shared the experiences of speculum examinations and sexual health. Even love songs explored gender roles, with Lonely Man – co-written by Lees and Expensive’s Telfer – probing the concept of toxic masculinity.

Despite playing almost 50 gigs during their 18 months together and appearing on the cover of influential feminist magazine Spare Rib, the Stepney Sisters’ catalogue of forward-thinking pop never made it to tape. In the years that followed, spaces including OVA Music Studio would launch in north London alongside feminist record label Stroppy Cow, but in 1975 “you couldn’t go into a recording studio – it was a phenomenal sum of money”, Hogarth recalls. After the group performed their final show in the summer of 1976 supporting a no-show Desmond Dekker, their discography was left unheard.

“We were all exhausted,” says Gilfillan of their split. “We’d been gigging like mad … we were pulling against each other ideologically, which wasn’t antagonism – we were still trying to find our feet.” One divisive moment came when the band was offered a residency at a ski resort in Chamonix. Half wanted to improve their technique and master their instruments, the others immediately wrote the opportunity off because of fears they’d be “playing to capitalist pigs”, as Smith remembers. Gilfillan continues: “I was more on that end of the spectrum. I was rather puritanical – I didn’t want to sell out.”

During their long hiatus, some members continued performing and writing. Smith performed in the reggae and ska collective Guest Stars, while Hogarth brushed shoulders with another group of uncompromising women: “I was briefly interviewed to replace Palmolive for the Slits. But Marguerite [from the Innocents] was cross and rang them up and told them that I was a heroin addict – which I wasn’t – so they rejected me on her advice.”

It wasn’t until the late summer of 2009, almost 30 years after their last show, that the Stepney Sisters regrouped for Hogarth’s 60th birthday. Committing to three days of rehearsals among the gift-giving, the band then played a reunion gig at the Half Moon pub in Putney, London. “They came in their coach-loads, the old girls, from all over the country,” Hogarth says. “The whole place was stuffed with laughing women. Even Jimmy Page made it!”

A year later, they finally laid down their debut album, full of bright upstroke guitars, climbing horns, and those signature soul vocals. “When I heard the CD, I realised we’d actually made something,” Ardill says. “The original songwriting was in the mid-1970s – it’s a time slip, but I don’t think it invalidates it.”

Radical women in music have made huge strides since the Stepney Sisters’ formation, from punk to the 90s riot grrrl scene to a new wave that includes Ardill’s daughter Anya Pearson, who performs in punk band Dream Nails and is now a labelmate with her mum. Pearson is thrilled to see her and her trailblazing friends receive the recognition they deserve. “When I was young, my mum taught me how to play guitar and encouraged me to start a band,” she says. “I grew up hearing stories of the Stepney Sisters’ exploits – feminist music has been around a lot longer than many people realise.”

With women now fully acknowledged by the industry – indie rocker Phoebe Bridgers is up for four Grammy awards this year, for example – do the band feel they were denied a place in rock history? “A lot of the bands that got publicity were still very much into image, and we weren’t,” Smith says. “People didn’t know – or wouldn’t have known – how to market us.” Instead, Lees says, “the Stepney Sisters was all sorts of things: a consciousness-raising support group, a practical help group, a loaning-of-money group”. Smith agrees that they go far beyond music: “The bond we have is very deep. It’s like family.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion