Juliana Hatfield speaks with deliberation: her thoughts unfurl after pregnant pauses and are sharpened by astute clarifications. “I’m sorry, I lost my train of thought,” she says at one point, doubling back to ensure her meaning is clear. Such consideration isn’t a surprise, given the rippling effect of an infamous early-career interview.

Nearly 30 years ago, while promoting her debut solo album Hey Babe, 23-year-old Hatfield, who was brand new to interviews, admitted to an inquiring male journalist that she was still a virgin. The casual comment became the focus of his piece, and incited scrutiny that followed the American songwriter throughout her rise. “When I was in the thick of it, it wasn’t really computing for me,” she says on a phone call from her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “It wasn’t until much later that I realised how intense it was, how gross it was, and how it affected my career in negative ways.”

Cynics viewed the admission as a strategic attempt to bolster her girlish image. Hatfield’s dulcet singing was already a point of contention among critics. “People thought it was put on, like I was trying to be coy or flirtatious, which is crazy because I was born with that voice and above all I was trying to be honest,” she says. As Hatfield’s second album, Become What You Are, climbed the alternative charts with its bubbly, slightly askew guitar-centric sound, coverage focused on her sex life, particularly her relationship with Evan Dando of the Lemonheads, a friend and bandmate. “At the time, I’d try to laugh it off,” she says. “I was on tour a lot, or I was recording and trying to keep my head down and work.” But the headlines were appalling. “Birds Do It, Bees Do It, But Have Evan and Juliana Done It?” Melody Maker asked on the cover of its November 1993 issue. “I was so clueless about all this stuff, about sexism and image,” Hatfield says. “I just thought my music would speak for itself.”

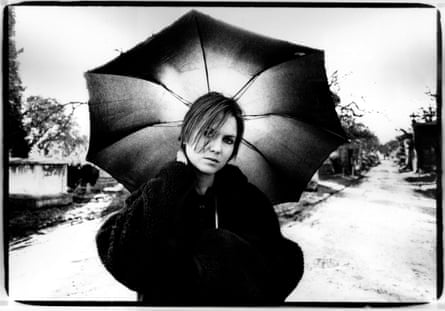

Eighteen solo albums later, Hatfield is set to release her excellent latest, Blood, an album that is both a reinvention and a return to form; she releases it amid a new generation of female songwriters – such as Soccer Mommy, Snail Mail, Julien Baker and Phoebe Bridgers – whose fierce yet melodic and thoroughly feminine sounds are implicitly linked to Hatfield’s in the 1990s. Blood furthers Hatfield’s skill for pairing hard with soft; her seraphic voice sings of fever dreams, anger and frustration, much of it spurred by four years of the Trump administration. “I think it’s really healthy to explore darkness in artwork and music, better to breathe it out rather than push it down,” she says. Its pop hooks are laced with formidable waves of guitar distortion.

It’s also the first album she’s recorded almost entirely on her own, playing most of the instruments at her home studio amid the coronavirus pandemic. “It was not a seamless experience,” she says. “Sometimes I would only work for like an hour and then I would get frustrated by the technology. It took me a lot longer to finish.” The resulting 10 songs take you into Hatfield’s inner world as it truly is: vibrant, unpredictable and messy, rather than tamed and neatly packaged for the outside. Mellotron flutes, synth washes, dextrous guitar playing and understated drum beats build a tightly stitched yet dreamy framework around Hatfield’s voice, an instrument she once tried to roughen up via cigarette smoking, but now accepts for its uniqueness. “Some great technical singers don’t have that,” she says. “I don’t really sound like anyone else.”

The 53-year-old was born in Wiscasset, Maine, and raised in the Boston suburb of Duxbury. In 1986, she co-founded the indie-rock trio Blake Babies as a student at the Berklee College of Music. Though they played the same clubs as fellow Bostonians Pixies, Dinosaur Jr and the Lemonheads, Blake Babies are cult favourites in comparison. “We were overshadowed by the more hyped bands around us,” Hatfield says.

In 1991, she recorded her first solo album and began collaborating with the Lemonheads, supplying bass and backing vocals on the band’s 1992 breakthrough It’s a Shame About Ray. By the mid-90s, Hatfield’s albums Become What You Are and Only Everything were staples on alternative radio and music television; Spin the Bottle, a buoyant pop-rock charmer written in 5/4 time, was featured on the soundtrack of the 1994 slacker dramedy Reality Bites. The following year, Hatfield made her acting debut on the teen television show My So-Called Life, after writing a song for its Christmas episode. “Everyone was really nice, and they were coaching me through it, but I definitely felt like a fish out of water,” she says. Cartoon delinquents Beavis and Butt-Head even spewed debased commentary while watching her music videos.

Hatfield’s unrepentantly feminine singing and skilled guitar playing took up space in a male-dominated alternative rock landscape, but she was unafraid to give voice to the anger, fear and longing experienced by many women and girls, singing of sisters, crushes, body image and broken hearts. “Making music has always been really helpful emotionally, to work through difficult and confusing situations and emotions,” she says. “We [women and girls] get confused because when we get angry, we don’t know what to do with that anger because we’re not encouraged to express it or even feel it. So then we start turning our anger inward on to ourselves. We start hurting ourselves or imploding.” Hatfield is no stranger to the cycle. Her career with major labels all but ended after she cancelled the European portion of the Only Everything tour due to depression in 1995. She has also struggled with anorexia and disordered eating.

On Blood, she channels these complex emotions into tuneful, three-minute vignettes whose lyrics often teem with anxiety, horror and existential dread. “A lot of bad stuff has been happening over the last four years, and the last year in particular, and writing was a way for me to deal,” Hatfield says. “Writing these songs didn’t cure me of all the anger but it definitely helped.” Throughout the album, she dreams about stabbing the former president, describes life in a world controlled by fascists, bites her tongue until it bleeds and is paralysed by love. Hard truths are conveyed through fantasy and imagined brutality, like a cleverer Game of Thrones. “In my real life I’m obviously not a violent person, and writing these songs doesn’t mean I want to go out and stab someone,” she says. “It’s a metaphorical stabbing.” Hatfield is doing what she’s always done: relaying dark, vulnerable and embarrassing feelings with remarkable insight.

Over the last year, Hatfield has found another form of release. The gym she frequents has been closed, so she’s taken up running, something she used to do in college. The practice doesn’t clear her mind, but it does reduce the noise. “It’s not exactly meditative because I’m very present, aware of everything that’s going on around me, but not focused on anything but taking steps,” she says. As for the continued speculation about her friend Evan Dando, which has been intermittently fanned by the pair’s interactions on Twitter? “We’re playing along in a way,” she says. “We don’t have to answer the question. Let them keep guessing.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion