A unique brain shape may be why the ancestors of living birds survived the mass extinction that claimed all other known dinosaurs, according to research on a newly discovered bird fossil.

“Living birds have brains more complex than any known animals except mammals,” says lead investigator Christopher Torres, who conducted the research while earning a PhD at the University of Texas at Austin, and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio University and research associate at the University of Texas Jackson School of Geosciences.

“This new fossil finally lets us test the idea that those brains played a major role in their survival.”

The fossil is about 70 million years old and has a nearly complete skull, a rare occurrence in the fossil record that allowed the scientists to compare the ancient bird to birds living today.

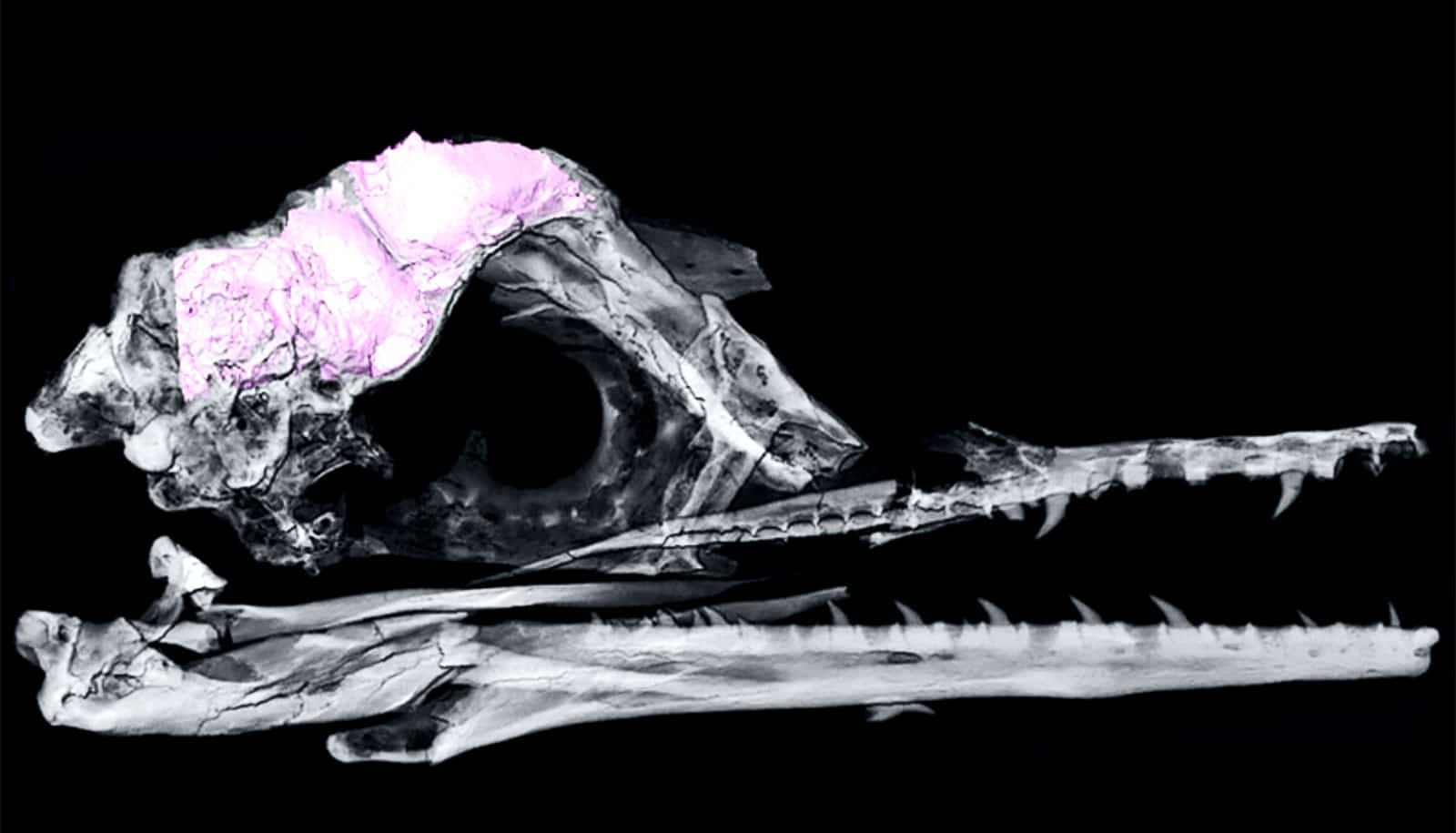

The fossil is a new specimen of a bird named Ichthyornis, which went extinct at the same time as other nonavian dinosaurs and lived in what is now Kansas during the late Cretaceous Period. Ichthyornis has a blend of avian and nonavian dinosaur-like characteristics—including jaws full of teeth but tipped with a beak. The intact skull let Torres and his collaborators get a closer look at the brain.

Bird skulls wrap tightly around their brains. With CT-imaging data, the researchers used the skull of Ichthyornis like a mold to create a 3D replica of its brain called an endocast. They compared that endocast with ones created for living birds and more distant dinosaurian relatives.

The researchers found that the brain of Ichthyornis had more in common with nonavian dinosaurs than living birds. In particular, the cerebral hemispheres—where higher cognitive functions such as speech, thought, and emotion occur in humans—are much bigger in living birds than in Ichthyornis. That pattern suggests that these functions could be connected to surviving the mass extinction.

“If a feature of the brain affected survivorship, we would expect it to be present in the survivors but absent in the casualties, like Ichthyornis,” says Torres. “That’s exactly what we see here.”

The search for skulls from early birds and closely related dinosaurs has challenged paleontologists for centuries. Bird skeletons are notoriously brittle and rarely survive in the fossil record intact in three dimensions. Well-preserved skulls are particularly rare—but that’s exactly what scientists need in order to understand what their brains were like in life.

“Ichthyornis is key to unraveling that mystery,” says coauthor Julia Clarke, a professor at the Jackson School of Geosciences. “This fossil helps bring us much closer to answering some persistent questions concerning living birds and their survivorship among dinosaurs.”

Mark Norell, the curator and division chair of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, cowrote the study, which appears in Science Advances. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute Science Education Program, the Jackson School of Geosciences, and the American Museum of Natural History funded the work.

Source: UT Austin